On the day of 1st Lt. Neil Burgess Hayes’ death, his brother, Rev. James “Jim” Hayes, S.J., ’72, unaware of the tragedy, felt a fire from within, a sensation so strong that it impelled him to pray the rosary immediately.

It was May 22, 1970, and Fr. Hayes was driving home to Michigan with a classmate. Neil, his eldest brother, was a soldier fighting in Vietnam.

“I remember it vividly,” Fr. Hayes says. “We drove all night. It was about 2 o’clock in the morning. My friend was asleep. I was driving and thinking about Neil, and I felt this significant burning sensation throughout my body. Something told me to pray for him.”

Days later, the family received news that Neil had died in a helicopter crash, shot down by enemy fire. In the aftermath, the Hayes family experienced unimaginable grief, but also expressions of consolation — inspiring and surprising — ones that would affect Fr. Hayes deeply, and set the course of his future ministry.

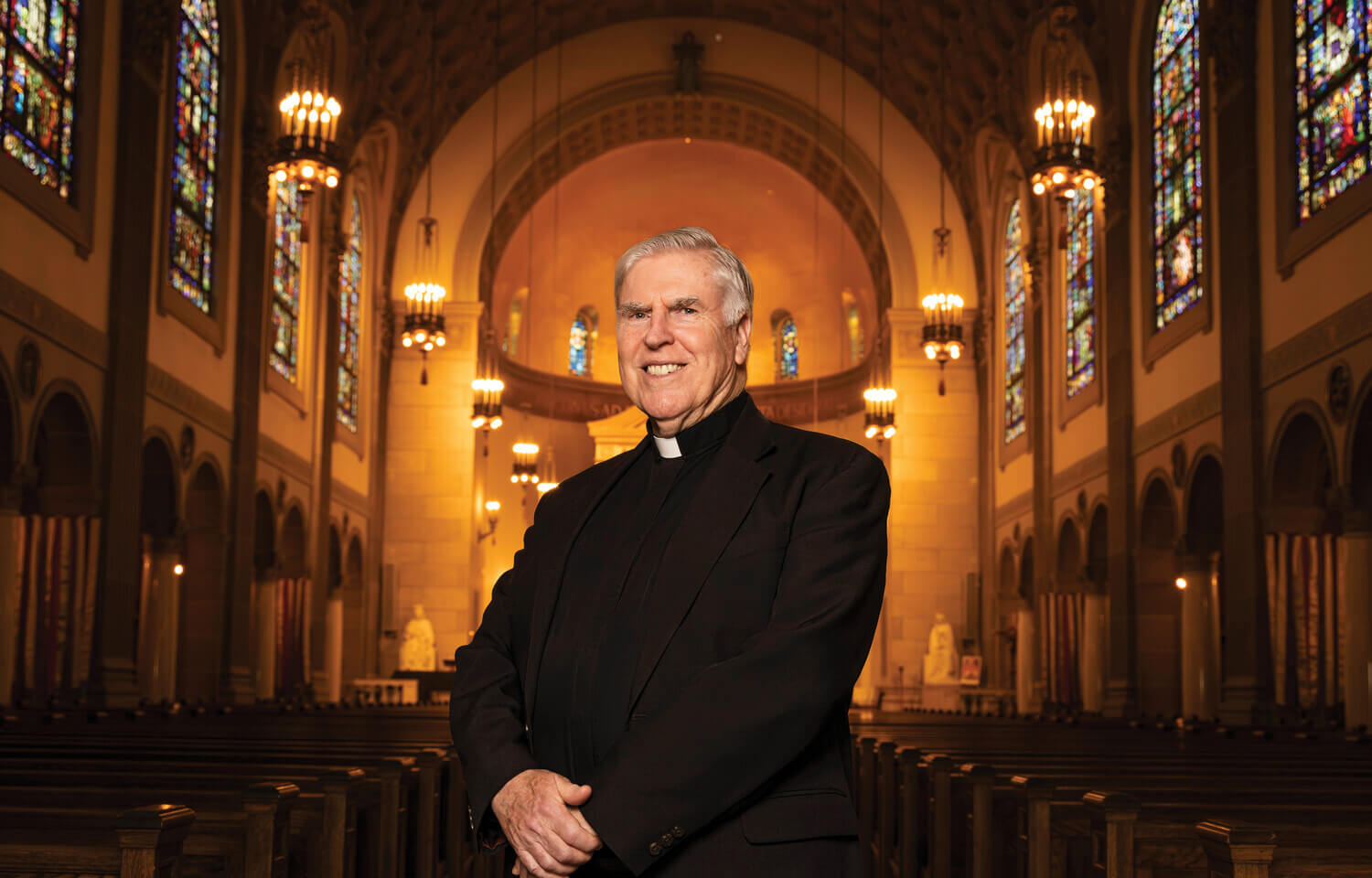

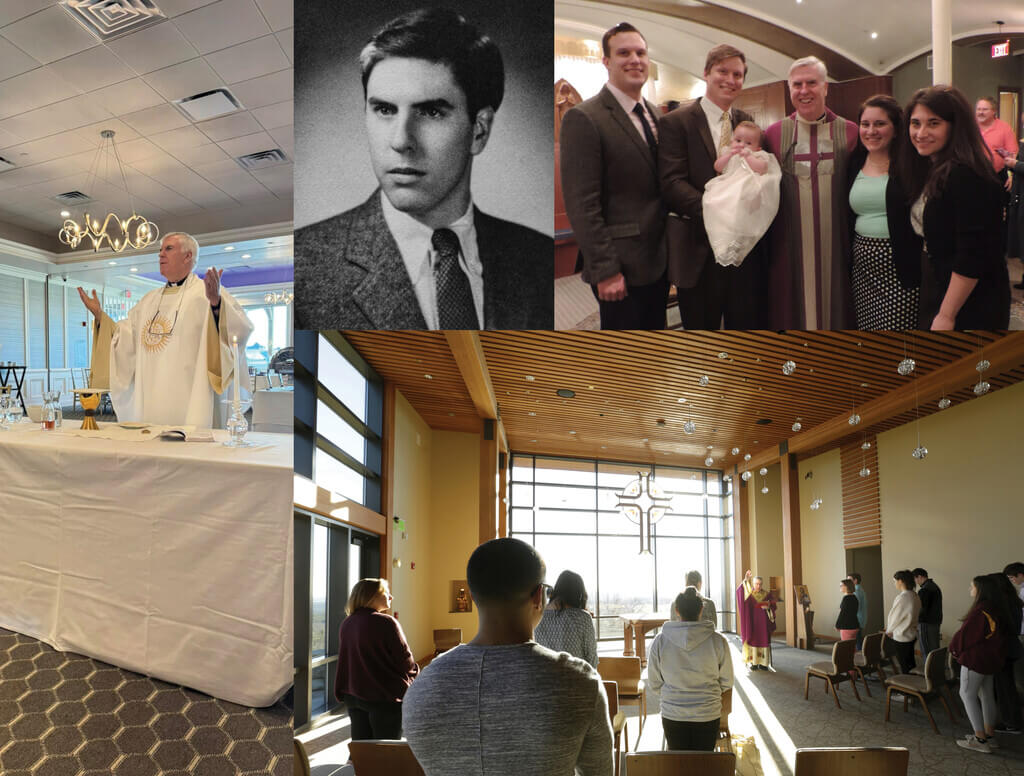

In spring 2025, Fr. Hayes retired from his role as associate chaplain for mission. In his more than 25-year tenure at Holy Cross, he served in a variety of roles. He was superior of the Jesuit community from August 2004 to July 2010. He chaired the College’s Mission and Identity Committee, served on the Holy Cross Alumni Association’s board of directors and was chaplain for the classes of 2015 and 2021. And, he’s officiated a lot of alumni weddings.

But for those members of the Holy Cross community who sustained the loss of a friend or family member during their time at the College, it may be Fr. Hayes’ Good Grief Bereavement Group that they’ll remember. Fr. Hayes initiated and supervised the group for 18 years, holding regular meetings and dinners, providing space and time for members to share and examine their grief together. Leading such a group is less of a top-down experience than an expression of solidarity, Fr. Hayes says. Grief shared, he notes, can do more than rescue people from feelings of desolation and aloneness.

According to the Spiritual Exercises, the foundation of Ignatian spirituality written by St. Ignatius of Loyola, desolation and consolation are states of being rather than feelings. Desolation is an alienation from God, Ignatius says, whereas consolation is an interior movement toward God that leads to a deep sense of peace.

Consolation, then, can and does exist alongside grief, sorrow or contrition.

“What I’ve learned is that consolation is a movement in our spirit,” Fr. Hayes says. “It’s often a grace, a gift that we’re given. And if we strive to engage in the ministry of consolation, then I think we listen attentively and strive to bring the good out of what another person is sharing with us and encourage them to see things in a new way, from a new perspective.”

For Fr. Hayes, this is not a theoretical argument; it is a lived and evolving experience.

“Jesuits are not afraid of death; it’s just a door,” he says. “I don’t know how you deal with it if you don’t have faith, but it doesn’t disturb me to hear people talk about their loss. I want to hear about it.”

‘NOW STICK TOGETHER’

Two months before Neil Hayes’ death, in the early spring of 1970, he sent his four brothers an open letter — bearing a hint of reprimand. He had just left the states for training in Panama.

The family had gathered in Worcester for a send-off dinner for Neil. Their conversation had been, in his brother’s words, shallow, Fr. Hayes recalls.

“He was anticipating, first of all, going to jungle school, which was a month in Panama and on to Vietnam,” Fr. Hayes explains. “So, he’s in a heavy sort of place, and I’m a sophomore at Holy Cross and I’m in a carefree place, in a way.”

It bears mentioning here that, in talking about his brother, Fr. Hayes often switches tenses, past to present, back and forth, sometimes in the same sentence. Spend enough time in his company and you realize this is no accident; this is the language of belief in eternal life.

Back to the letter: In big brother fashion, Neil issued orders to his younger siblings.

“Now stick together,” he wrote, along with a wish that the brothers look out for his newlywed wife, Paula. Of the future Fr. Hayes, Neil wrote: “Jim seems a little confused about the Navy and his future. Is he still thinking about the priesthood?”

Fr. Hayes grins at the memory: “I thought, What is he talking about? I did want to be a priest when I was little, until I was 12, then girls came into the picture.”

An English major, he was also thinking about a career in architecture or, perhaps, he’d follow the path of his father, Neil B. Hayes ’32, an attorney for the Archdiocese of Detroit. In the wake of Neil’s death, though, Fr. Hayes was moved by the consolation he felt from classmates and, especially, the two Jesuits and one lay professor who traveled from Worcester to Detroit to attend the funeral.

After the funeral, Neil’s wife discovered she was expecting, a lasting consolation for the Hayes family.

“That was a joy for us in this loss,” he says. “There’s no death without new life: That’s the message of the Gospel. And we have to focus on the new life. We have to grieve, yes, Jesus says, ‘Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be comforted.’ So, we have to mourn and grieve, but we also have to pay attention to new life.”

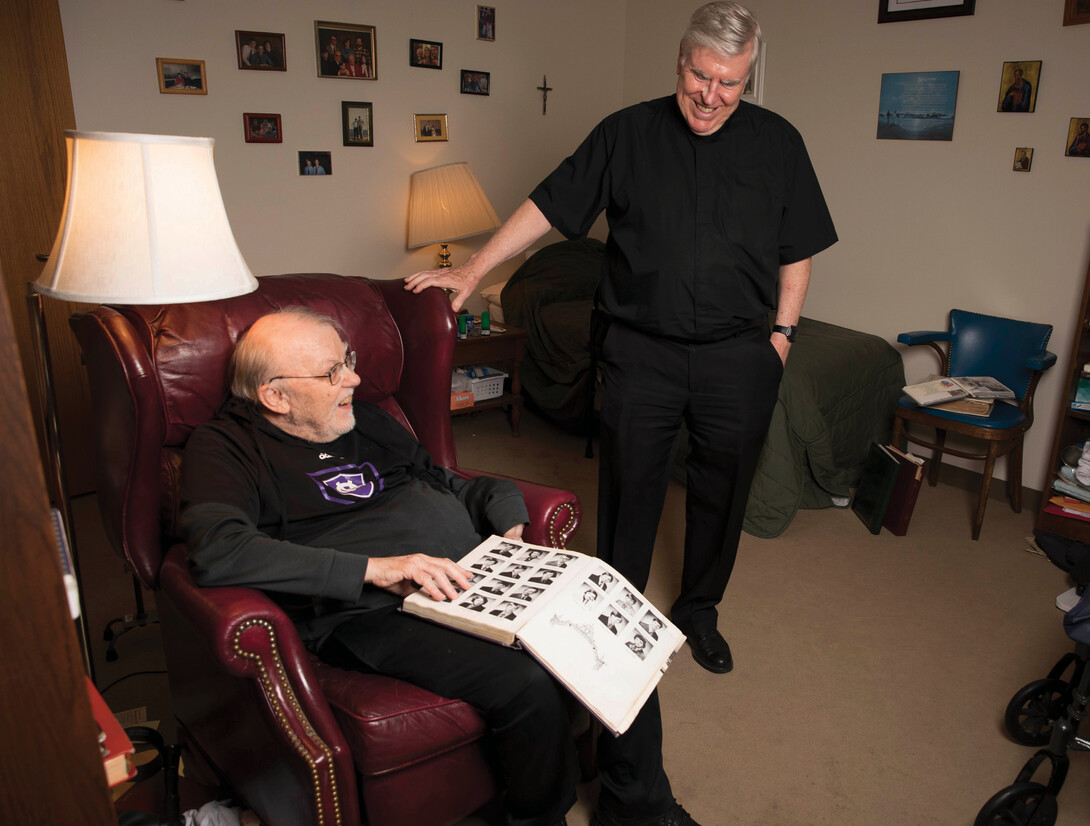

Neil Hayes III says that although he never met his father, his Uncle Jim made sure he knew him. The younger Hayes speaks of regular visits, long phone calls and the “shameless letter-writing campaign” his uncle has kept up over the years.

“Uncle Jim is my godfather, too. It’s pretty good luck on my part; it’s hard to get a lot more godly than that,” he says. “What is interesting about Jim is that he doesn’t have to have the first word or the last word, but he always has a compelling word. He’s most focused on how he can contribute something valuable and meaningful and deep to others. I don’t think he revels in the small talk; he revels in substance.”

In the telling of this part of his family story, Fr. Hayes recites a quote by German Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner that lands like a benediction:

“The great and sad mistake of many people, among them, even pious persons, is to imagine that those whom death has taken leave us. They do not leave us. They remain! ... We do not see them, but they see us. Their eyes, radiant with glory, are fixed upon our eyes full of tears. Oh, infinite consolation! Though invisible to us, our dead are not absent.”