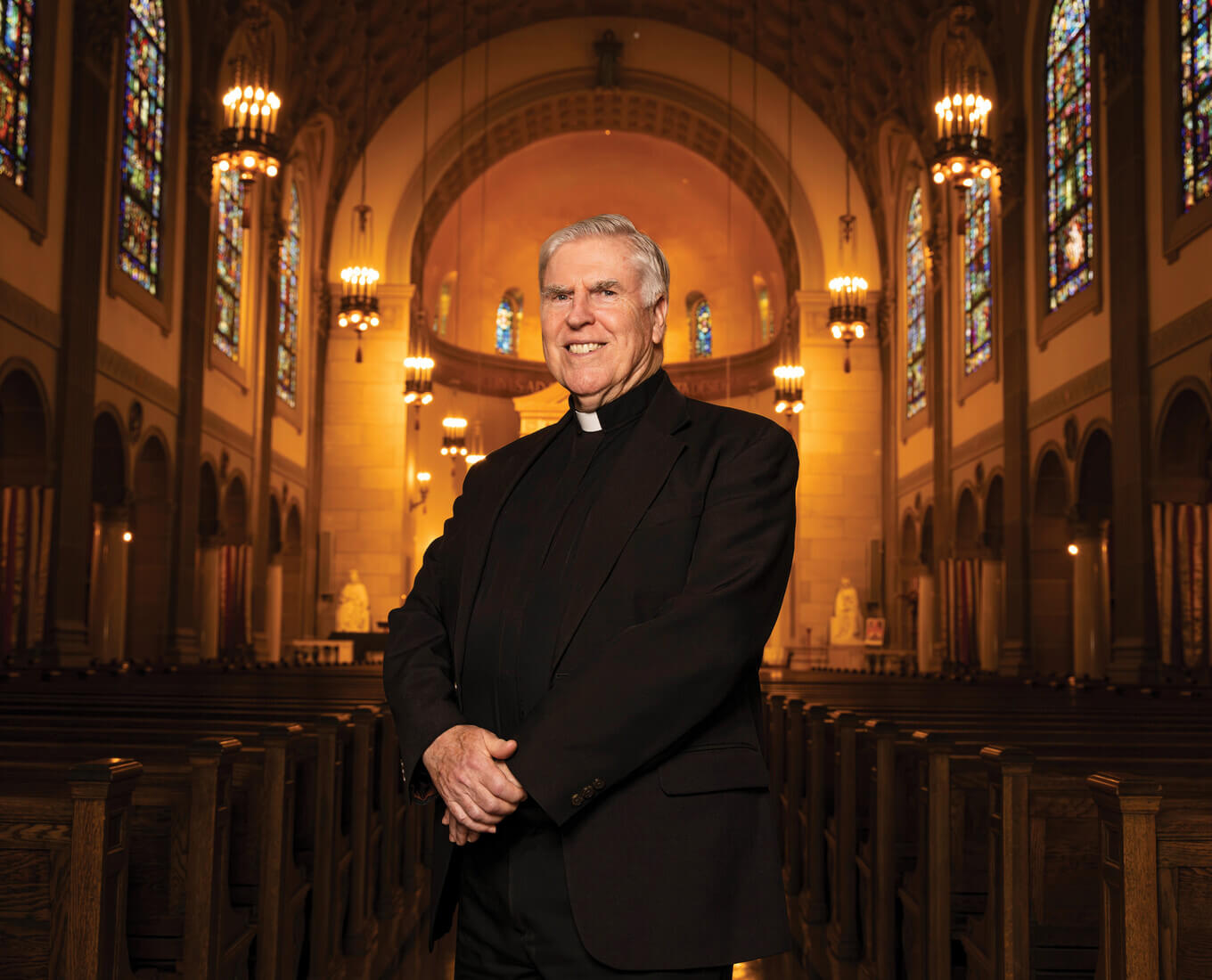

Two little girls, sisters, play in a garden.

The younger girl perches on a rock, knees bent slightly, ready to spring. The older girl has one foot on the rock and the other on the ground. She holds one of her sister’s hands in hers. They are barefoot and sharing a moment of full-throated laughter. With their glossy black hair and spotless white rompers, the pair calls to mind fairytales in which children transform into songbirds: two chickadees caught midmelody in the moment before taking flight.

The scene is captured in a photograph produced by Professor Florencia “Flo” Anggoro when asked about her childhood growing up in Indonesia. (She’s the younger girl, the child about to leap.) The older girl is her sister, Felicia. Just a year and a month apart in age, they were mistaken for — and often treated like — twins growing up. They liked it that way. The two shared everything: a room, clothes and taste in music (New Kids on the Block, then Bon Jovi).

Anggoro, a professor of psychology and science coordinator at Holy Cross, calls her sister a force and uses words such as “fearless” and “trailblazer” to talk about her. Friends and family use similar words to describe Anggoro, usually coupled with the word “persistent.” Anggoro is an expert in language and conceptual development, science learning, relational thinking, and culture and cognition. Her research explores how children build conceptual knowledge about the world and how language and cultural ideas inform those concepts.

Put another way, Anggoro’s the person you wish you had on speed dial when, at the end of a long day, your child asks, “Where does the sun go at night?” or “Can Jesus walk through walls?”

More on that later. For now, know that Anggoro understood from a young age what she wanted to do, and she did it. But hers is not a story of effortless success. Like those children in fairytales, Anggoro would confront formidable, even life-threatening, challenges. Armed with only her wits and will, she would meet and surmount daunting obstacles and, in the process, gain an understanding of what children — and her students — are capable of, given the right support.

° ° ° ° °

Some must cultivate persistence. Others are powered by it. Anggoro falls into the latter category, says friend and colleague Danuta Bukatko, distinguished professor of education and psychology.

“If you look at Flo’s grant-getting experience, I would say she’s one of the more successful faculty members at the College,” Bukatko says. “I think persistence is a big part of that. For her, the ultimate goal is to engage people in the richness, excitement and reward of doing science.”

Anggoro made up her mind to study psychology at the age of 8. Her mother, also a psychologist, ran a counseling practice from their home in Jakarta, Indonesia, and enlisted her youngest daughter’s help with clients who arrived for their appointments with their children in tow. Anggoro loved being her mother’s apprentice.

“My mother thought [the kids] would be helped by my presence, and so she would give me a little background and then let me sit in on sessions,” Anggoro recalls. “Afterwards, sometimes, she would talk about it with me.”

She laughs at the memory.

“She probably broke some rules, but I loved it,” Anggoro says. “All I knew was that psychology was about helping people with their problems.”

Anggoro’s parents, Budyharto Anggoro and Jeanne Arijanti (her mother kept her maiden name), came from small towns in Central Java, Indonesia. Arijanti was the only girl and the youngest in a traditional family that believed in investing in sons.

“My mom wanted to study psychology,” Anggoro says. “But this was the 1970s in Central Java. Can you imagine that uphill battle? Her parents were, like, ‘All of our investments will be for the boys. We’re going to send them to Germany for school, and they’ll study engineering.’”

Her mother stayed home and attended the top university in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, for psychology.

“She was the only one of all of her siblings to graduate college,” Anggoro notes in a How-do-you-like-them-apples? tone.

Anggoro is the middle child in her family, followed by her younger brother, Juventus. Her parents were successful and financially comfortable when the children were young. Unlike many of their generation, they believed their children should have a choice in how they spent their professional lives. Be pragmatic about it, they said, but pursue your interests.

“My mom thought I would be good at marketing, at using my observational or speaking skills — what she’d observed in me,” Anggoro says. “My sister is like my father: artistic.” When Anggoro was 17, her sister left home to pursue a graphic design degree at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore.

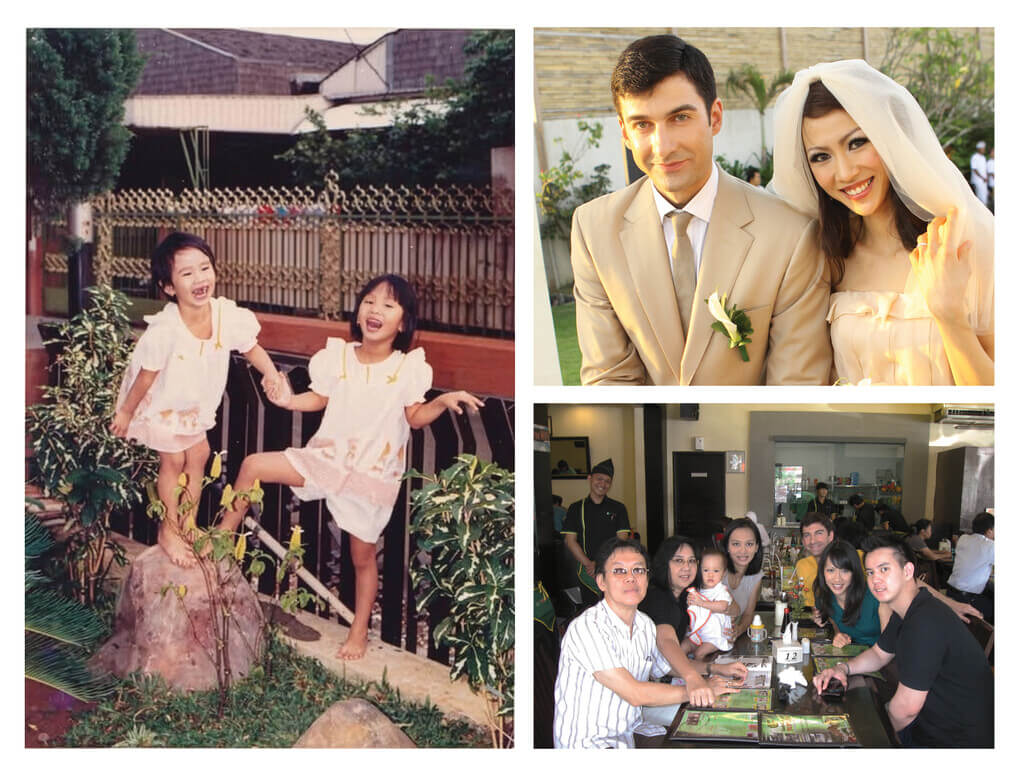

The plan was for Anggoro to follow in her sister’s footsteps, graduate from an American university and then return to her family in Indonesia. She would marry her boyfriend of eight-and-a-half years, whose brother, as it happens, later became Felicia’s husband. They would move into the house her fiancé’s family was building for them, next door to the one they were building for Felicia. The sisters would be next-door neighbors — and sisters-in-law.

It was all arranged until it was all undone.

Anggoro’s parents are third-generation Chinese immigrants. They raised their children Catholic in the predominantly Muslim city of Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital and its largest city. The country requires its citizens to register their religious affiliation and to carry ID cards bearing that information. While this might read as extreme to Americans, Indonesians view it as evidence of tolerance of religious diversity. The Anggoro children were largely unaware of the tensions, ethnic and religious, that were brewing as the country’s economy faltered in the late 1990s.

“We’re a very tight-knit family, and we were pretty insulated in terms of what was going on in the outside world,” Anggoro says. “There’s no doubt in my mind that I could and can count on my parents for anything and everything. Their love was unquestionable, and they sacrificed everything.”

She produces another photo, taken when she was about 14. This one shows a thoughtful adolescent Anggoro wearing a tentative smile. Hands on her knees, sporting a baseball cap and green plaid skirt, Anggoro poses with her crew.

Here is where the “sacrifice” begins, and it is neither metaphor nor platitude; Indonesia was becoming a dangerous place for the Anggoro family.

Families with means sent their children to the best Catholic schools they could afford. Anggoro’s parents enrolled their daughters at St. Ursula Jakarta, a prestigious and rigorous all-girls school. School was held six days a week, and days started at 7 a.m.

“We were out the door by six to make it to school on time,” Anggoro says. Scholastically, St. Ursula was a place where they could realize their shared dream of going to college in America. Felicia embraced the arts. Anggoro chose the social sciences track.

“Three years of junior high school, three years of high school,” Anggoro recalls. “It was an extremely formative experience in some ways. Not so good for me in other ways. I loved my friends, but disliked the school.”

St. Ursula’s was strict. Uniforms, prim white shirts, knee-length green plaid skirts and white knee socks, were subject to surprise inspection for holes. Hair was to be pulled back from the face. No makeup. No jewelry. It was an environment intended to eliminate distraction — an ideal setting for adolescent rebellion.

“I was part of this group of girls, and we really just wanted boys’ attention,” Anggoro says, then smiles. “We would go to basketball games at partner schools. There was this other girls school that we’d compete with. They’d get all the boys because the school was less strict, and they looked sassier.”

So, at one game, Anggoro and her friends rolled the waistbands of their skirts to show a little knee, at most an inch between the hem and knee sock.

“I almost got kicked out of school for that,” she says, disbelief still registering in her face and her tone. “I was a junior, and some of the senior girls reported us.”

The public shaming was swift, harsh and sneaky. By “reported,” Anggoro means someone posted a public notice of the girls’ behavior. In the days before social media, public posting happened on the school’s prayer board.

“The prayer board was this big white board in front of the auditorium. Everybody would write down their prayer for the day, like, ‘I’m praying for my grandma who’s sick’ or ‘I’m praying for our class that has a history exam today,’” Anggoro explains.

The day after the basketball game, an anonymous note posted on the prayer board read, “I’m praying for the junior girls who embarrassed our school by shortening their skirts.”

“And that’s how we got caught,” she says. “We all had to stand in front of the auditorium wearing signs that said what we had done and why, and the senior girls yelled at us.”

The experience was traumatic for Anggoro. One of her friends left the school. What Anggoro’s mother did next, though, was to give a horrendous situation as much of a happy ending as could be had under the circumstances.

“My mom didn’t get mad at me; she got it,” Anggoro recalls. “She said, ‘Whatever the punishment is, you will do it,’ but she felt it was a cool thing to do: to rebel a bit and develop mentally.

“I told myself, ‘I’m not going to set foot in that building again once I’m done,’” Anggoro continues. “None of my friends felt the way I did. They just accepted it. They think of their personalities as having been positively formed; they’re proud of having been through that gauntlet.”

Anggoro parts ways with her friends there, focusing on the action rather than its aftermath.

“I’m proud of my rebellion,” she says. “I guess I have an independent streak.”

That streak would be tested in ways her then 16-year-old self couldn’t begin to imagine.

° ° ° ° °

In 1997, the year Anggoro’s sister left for college, the Asian financial market collapsed. Indonesia’s official currency, the rupiah, plummeted in value. Suddenly, Felicia Anggoro’s already-expensive American education cost seven times more. Anggoro saw the strain the family’s change of fortune had on her parents. Though she’d already applied to several American schools, Anggoro offered to attend the local university to ease the financial burden.

“We found this program that was two years in Indonesia and then your credits could transfer to a college in the States,” Anggoro says. “I was going to apply. I was in high spirits; I could still graduate from a United States university.”

One day, though, she found herself the target of unwelcome attention as she walked to an appointment with university officials to talk about the program.

“There was a bunch of guys on the street staring at me, and my dad just couldn’t let me do it,” Anggoro says. “He felt I was going to be targeted.”

When the economy tanked, tensions exploded between Indonesia’s citizens, especially between native and Chinese Indonesians, Anggoro explains. There were riots. Chinese homes were attacked. Businesses were looted and burned. People were beaten. Women were raped.

“Houses were marked if there were Chinese girls in there; girls were more of a target,” Anggoro says. “And, oh, my God, we had a big house at that time. It was just me, my parents and my little brother. Every day we were on the phone trying to get information about what areas were more or less safe.

“My relatives in Central Java lost their houses and shops,” she says. “They were burned.”

People who could afford to leave did. One Friday, Anggoro’s parents heard a rumor that gangs would be attacking Chinese households later that day.

The family gathered in the living room, held hands and prayed while native Indonesians, employees of Anggoro’s father, stood guard at the gate in front of the family home.

“At around 2 or 3 a.m., we heard the loudest banging on our door. I’d never seen my parents so scared,” Anggoro says. “We grabbed anything we could and ran towards the back of the house because that’s where our neighbors were.”

They ran into the night, making as much noise as they could to alert their neighbors, who ran to their defense, armed with baseball bats.

“We were imagining a mass of people at the gate, trying to raid our house, to torture and attack us,” Anggoro says. She tore one of her hands open scrambling over a fence: “I still remember the blood on my hands.”

It turned out to be a false alarm, perhaps the banging was some random thug looking for an unlocked door, Anggoro posits.

That was May 1998. Despite their precarious financial situation, the Anggoro family made the decision to send their second daughter to the United States; in the moment, it was as much for her safety as it was for an education. Two months later, Anggoro was on a plane to Baltimore to stay a month with her 18-year-old sister.

Two oceans and 10,000 miles’ distance from Jakarta and its riots sparked excitement and apprehension in Anggoro. She’d been accepted to several American universities and chose Indiana University, sight unseen. But how to pay for it? The Anggoro sisters’ financial circumstances were dire.

Again, Anggoro looked to Felicia’s example.

“My sister is the more calm, agreeable one,” she says. “I was absolutely the more rebellious, outspoken one, but she was my trailblazer. She has no fear, whatsoever, of trying new things — even though she is kind of reserved. She has a quiet confidence.”

Anggoro tears up: “She made me more willing to take risks.”

Both sisters scraped by with small jobs and scholarships. For Anggoro, the ensuing years of bachelor’s to master’s to Ph.D. were thrilling and terrifying in equal measure. Each semester’s tuition bill got paid, but Anggoro operated from a perspective that any given semester might be her last. She also struggled with self-doubt and professional jealousies, not uncommon in competitive academic programs. Still, Anggoro completed her undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in three years (she transferred from Indiana), and in 2006, earned her Ph.D. from Northwestern University. She was just 25 years old.

It was time to go home.