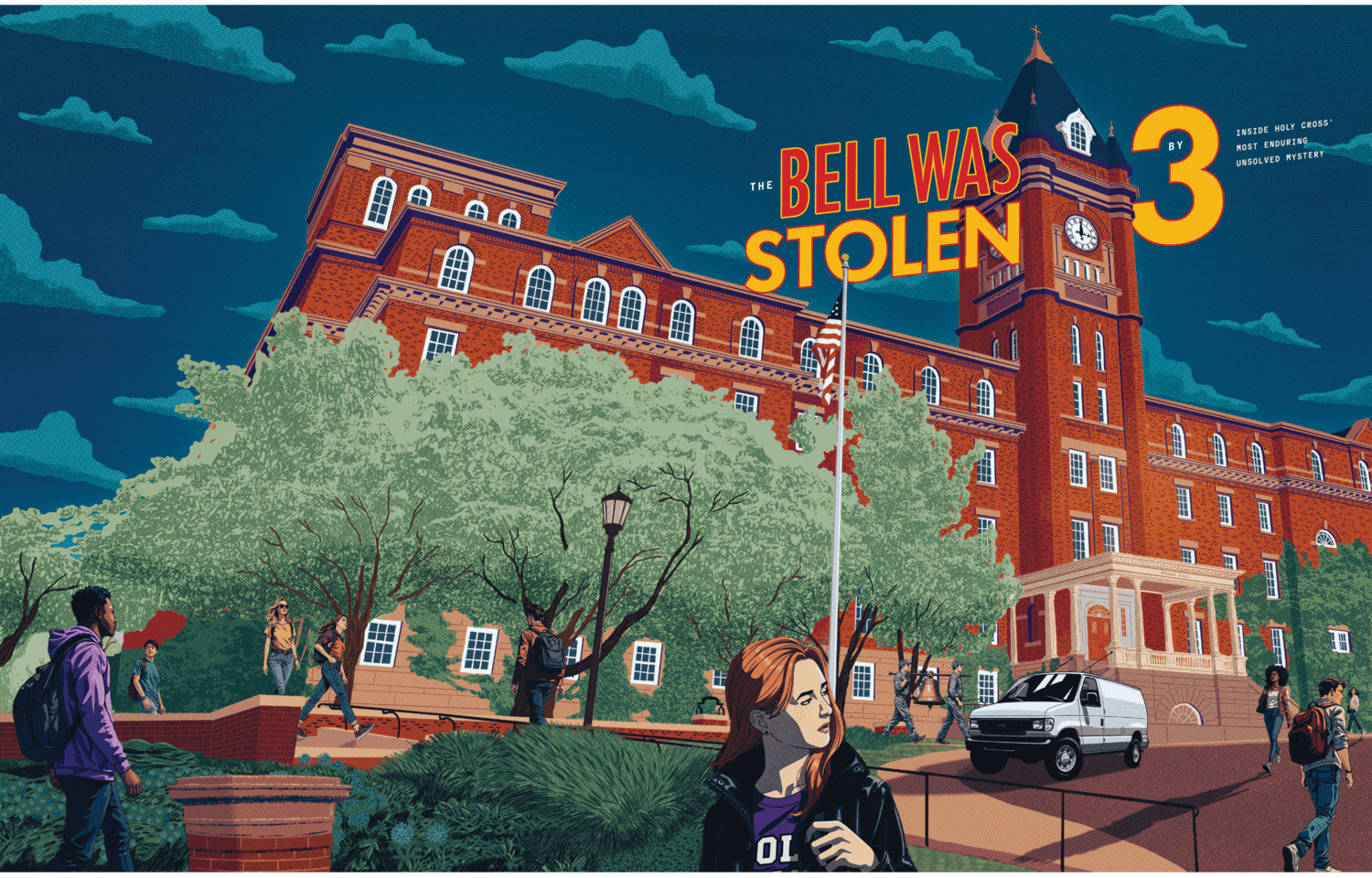

On a spring afternoon in 2009, at around 3 p.m., a student noticed six middle-aged men in crisp, matching coveralls exit a white van parked on Linden Lane. The vehicle sat between a guard shack, located in the middle of the College’s busy main entrance, and Holy Cross’ public safety office in the basement of O’Kane Hall. The area between teemed with hundreds of students walking to and from classes.

One of the men carried a wrench.

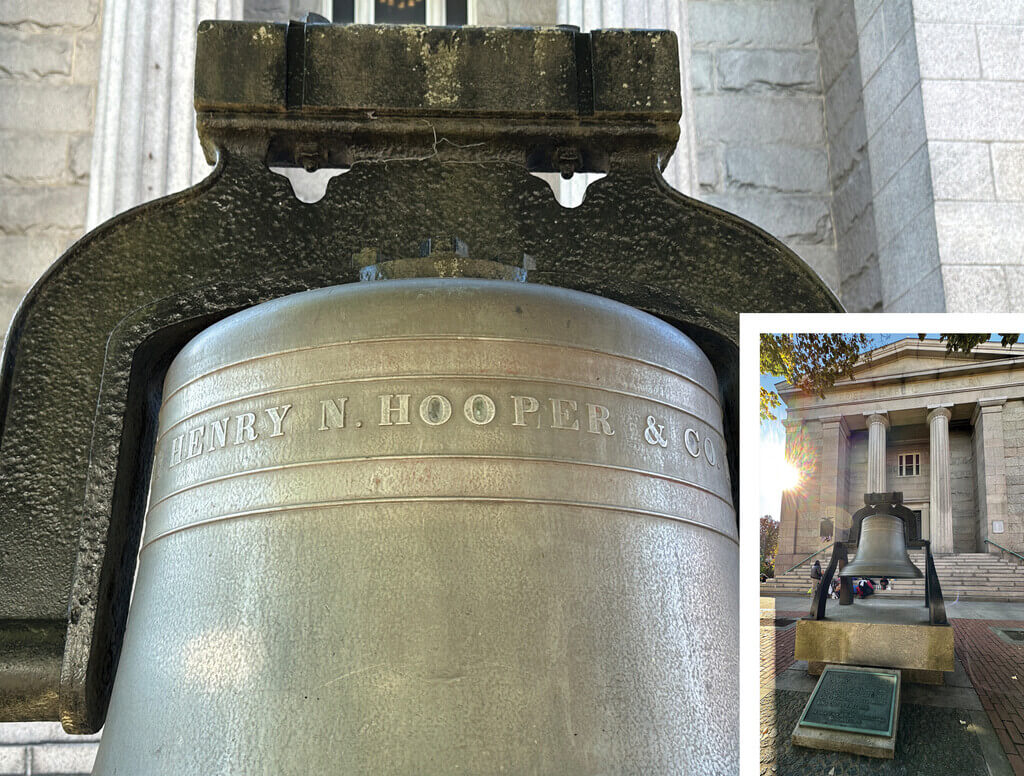

The student watched as the men removed the 400-pound, then-156-year-old bronze bell, commonly known as the Fenwick Tower Bell, from its stand on the lawn at the corner of Fenwick and O’Kane halls. The crew loaded it into the van and left the only way they could, via Linden Lane, a short, busy, U-shaped road offering one way in and one way out.

Only later, after calls were exchanged between the public safety and facilities departments, did College officials realize that the bell, a fixture on campus since 1854, had been stolen in broad daylight.

That detail about the timing of the theft still sticks with Sgt. Brian Hayes of public safety. Now in his 20th year at Holy Cross, he was a member of the department in 2009.

At the time, public safety’s shift change, he notes, was 3 p.m.

“They must’ve scoped it out,” Hayes posits. “They knew what they were doing; this was a professional job.”

If one were filed, no police report remains. No one has ever been charged in the heist, and the bell — relatively invisible in the three decades it sat on the O’Kane lawn, but infamous after its disappearance — has never been recovered.

But that’s not the end of the story.

STUDENT PRANK OR SOMETHING ELSE?

Over the years, three theories have emerged regarding the bell’s fate. College officials first thought the theft may have been a student prank. The second scenario is that the bell was melted and sold for scrap. A third: The bell ended up in a private collection.

Following the theft, members of the Holy Cross community received an email request for information that yielded just a single eyewitness account, from a female student. The student’s name is unknown. The email is not among College records. But search “Campus Bell is Missing,” and you’ll find an email in a discussion forum on collegeconfidential.com. Dated May 2009, the email reads like an official statement, and its alleged author was a College employee. Efforts to reach the former employee were unsuccessful. But, if the email is authentic, its overarching message is that the College initially treated the theft as a student stunt.

The email:

“Dear Students,

The approaching end of the academic year is a time to celebrate the accomplishments of the year and, in particular, the accomplishments of the Class of 2009. It is a time rich in history, tradition, and the promise of the future.

As some of you may have noticed, a piece of Holy Cross history has recently been missing. The bell that graces the lawn outside of O’Kane Hall disappeared two weeks ago. This solid bronze 400-pound bell was cast in 1853 by Henry Hooper, who took over Paul Revere’s foundry after Revere’s death in 1818. For over 100 years, the bell was mounted atop Fenwick Tower and daily tolled the ‘Angelus’ and ‘De Profundis,’ traditional Catholic prayers.

Public Safety has been searching for the bell, including contact with local metal salvage operations. So far, they have had no luck.”

The email then asks recipients to contact public safety with any information and closes on a no-harm-no-foul note:

“As we look ahead to Commencement, it is the hope of many in the Holy Cross community that the bell will find its way back (no questions asked!) to its place on the lawn outside of O’Kane Hall, where it may bid farewell to the Class of 2009 and be ready to welcome the Class of 2013.”

Nearly 20 years later, the prank theory doesn’t sit well with experts.

Sgt. Hayes recalls the FBI being contacted at the time and notes that law enforcement checked local flea markets for a year after its disappearance, but no new information — or the bell — surfaced. He reiterates that the theft was well planned and orchestrated: “They didn’t even leave a mark on the stanchion.”

The stanchion is the apparatus that holds the bell; it, the brick base and the plaque identifying the bell are all that remain.

Maybe.

FROM DAILY REMINDER TO “DEAD RINGER”

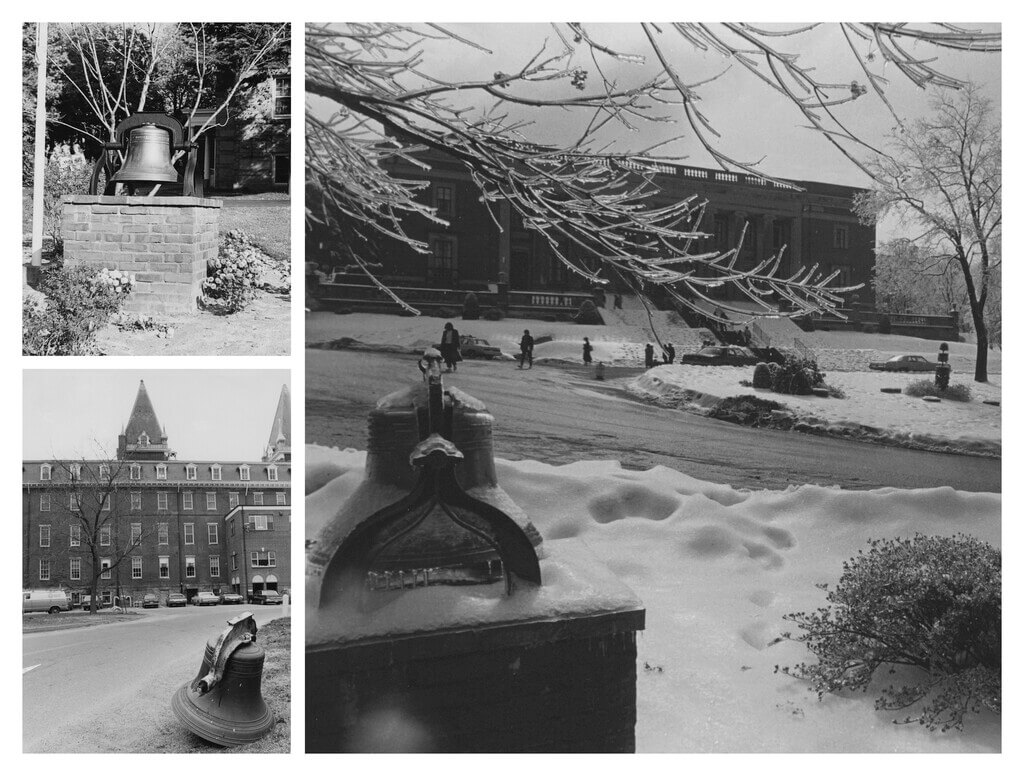

First, a little history: According to the article “Fenwick Bell Has a New Home” published in the September/October 1975 issue of Crossroads, the alumni magazine at the time, the bell was acquired by the College in 1854:

“The solid bronze, 400-pound bell, long the target of Holy Cross pranksters until it was removed from its casing atop Fenwick Hall in March 1974, has found a new resting place: a brick pedestal in front of O’Kane Hall.

“The bell has a long history. It was cast in 1853 by Henry M. Cooper [sic], who took over Paul Revere’s foundry in Boston after the latter’s death.”

[An important note: Henry Northey Hooper, not “Henry M. Cooper,” was Paul Revere’s apprentice at the patriot’s Boston bell foundry. Hooper purchased the foundry from Revere and renamed it Henry N. Hooper & Co. He developed a reputation for his bronze lighting fixtures and his bells, some of which still reside throughout New England, according to the Paul Revere Heritage Site in Canton, Massachusetts.]

“In 1854, the bell was mounted on Fenwick Hall, when the building was only two stories tall, and it was moved to one of the Fenwick towers when two more floors were added in 1867.”

When the bell was in use, it tolled to mark the beginning and end of the Jesuits’ day, according to the article.

“The bell rang out the ‘Angelus’ at 5:30 a.m., noon and 6 p.m., and finished its daily ensemble with ‘De Profundis’ at 9 p.m.,” according to the Crossroads article. “The ‘De Profundis’ was also tolled to announce the death of a member of the Jesuit community, and its measured, solemn tones marked the passage of his funeral cortège from the chapel to the Jesuit cemetery.”

The article concludes with the reason for the removal of the bell from its tower: “College officials feared that some would-be bell ringer might slip off the roof and fall 80 feet to the ground below.”

The Worcester Telegram also published a short article noting the bell’s relocation, which included a nod to pranksters: “... if anyone wants to ring the bell without making the traditional climb, he can’t. Foreseeing a possibility of ground-level noise, college officials have removed the clapper.”

The article’s headline: “A dead ringer.”

In fairness, it bears mention that Holy Cross students mounted a defense of their actions, addressing the issue in an editorial, “For whom the bell tolls,” published in the March 8, 1974, edition of the student newspaper, “The Crusader.” The editorial is a mock-elegy, lamenting the death of a time-honored, though objectively harebrained, tradition:

“The Bell’s removal will end a tradition that begins way back in Holy Cross history. Many alumni probably recall the times they braved the slippery roof and alerted the campus of their victorious ascent to the spires overlooking the campus. In those days, ringing the Bell probably ranked as highly as streaking does now. It was a star on the list of forbidden campus attractions, a challenge to those who wanted to do something different and still make the eleven o’clock bedcheck by the corridor priest. Ringing the Bell didn’t make national headlines; as far as we can determine, there was never an Association of Student Bell Ringers. But it was a tradition; and it was something to do; and many people did it; and, now, apparently, it won’t be done anymore.”

Bell-ringing, the writer contends, is a strike against the status quo, a salvo against complacency.

“It’s sad, in a way, that this tradition will be no more. There is no doubt that other fads will come, and that some of those fads will become traditions that we will tell others about after we leave Holy Cross. As the College changes, so do the traditions of the College. But it is nice to have a few traditions which are constant, which are passed down from class to class, which are always sure to evoke some reaction when they occur. We cannot argue that the ringing of the Bell isn’t dangerous. That was what made it exciting when you heard it ring; you knew someone was taking a chance. We don’t advocate students putting their lives in danger simply to ring a bell, but it was rather comforting to know that in this era of apathy, there were still some who would take a gamble.”

Clearly, the administration was unmoved.

And so the bell sat silent on the O’Kane lawn for 35 years, until 2009.

“THERE’S SOME OTHER MOTIVE”

About that prank theory: International crime theft expert and New York Times bestselling author Anthony Amore is head of security for Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, as well as its chief investigator. For 20 years, Amore has been investigating the infamous 1990 heist at the Gardner, in which two thieves dressed as Boston police officers stole 13 pieces of art, including a Rembrandt and a Vermeer, which they cut from their frames. Together, the stolen pieces’ value totals between $500 million and $1 billion. There is a $10 million reward for information that leads to the recovery of the still-missing artwork.

Amore’s fourth book, 2025’s “The Rembrandt Heist: The Story of a Criminal Genius, a Stolen Masterpiece, and an Enigmatic Friendship,” tells the story of Myles O’Connor, dubbed the world’s greatest art thief by Boston Magazine. On April 14, 1975, O’Connor and another man stole the Rembrandt painting “Portrait of Elisabeth Van Rijn” from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In broad daylight. During the museum’s operating hours.

All this is to say, Amore has extensive experience with art crime. And the Holy Cross heist strikes him as peculiar. Generally, people want to claim credit for a prank, he notes.

“Lots of crime happens on campuses,” Amore says. “They’re soft targets. This is weird, though, the idea that people went through this sort of planning to make a few hundred bucks.”

Amore is referring to the bell’s “melt value,” its worth in its liquid state. Bronze, which is 70 to 95 percent copper, is valued less than a pure metal. Copper’s value in 2009 hit a low of $1.48 per pound in January and a high of $3.16 in December, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. So, if six men stole Holy Cross’ copper bell at the height of the metal’s value in 2009, its melt value would be, at most, $1,246 — a payout of about $210 per thief. But, remember, bronze would fetch even less.

So, not a big score for a crime committed in broad daylight with hundreds of potential witnesses and in full view of the public safety office.

“You don’t go get a van and uniforms and risk getting arrested for $200, right?” Amore says. “So, I think there’s some other motive for stealing the bell. The key is figuring out what the motive is.”

TO MARKET WE WILL GO?

Todd Lower is the owner of Bellcastings, a company outside Knoxville, Tennessee, that sells and refurbishes large church bells. Lower also has doubts about the stealing-for-scrap theory. No legitimate scrapyard, foundry or bell dealer is going to buy a bell without paperwork. A party would need to produce a purchase order to sell such a bell to a reputable business, Lower maintains.

His default mode is laconic when cold-called about the 17-year-old case. Turns out, he’s heard it all before: A Holy Cross alumnus, whose name Lower can’t recall, has periodically contacted him over the years with similar questions.

“Hooper produced many bells. If Holy Cross knew the size of the bell, or if there were an inscription or a dedication on the bell, that would help in identifying it,” he adds. “It’s hard to remove an inscription from a bell.”

(While College Archives and Distinctive Collections keeps architectural drawings, building plans and purchase orders, a purchase order is not among the papers collected about the Fenwick Bell.)

So, what if thieves stole the bell not to melt it, but to sell it to a private collector or at the nearby Brimfield (Massachusetts) Antique Flea Markets? Held annually since 1959, Brimfield is the oldest and largest outdoor antique market in the country. Three times a year — spring, summer and fall — the weeklong events showcase 150 acres of antiques for sale and draw buyers and sellers from across the United States. And they’re held just 30 minutes west of Mount St. James. The bell was stolen in Spring 2009. Brimfield’s markets that year were held May 12-17, July 14-19 and Sept. 8-13.

“It might’ve shown up at a Brimfield, or another flea market,” Lower says. “That’s a great place to sell a bell.”

A stolen item has turned up at a Brimfield show. According to the newspaper Antiques And The Arts Weekly, a Litchfield, Connecticut, antiques dealer and collector purchased a late 18th-century needlepoint sampler embroidered with “When This You See/ Remember Me/ Matilda Cone Aged 9 Years/ East Haddam 1799” at Brimfield in 2015. When researching the piece, the dealer learned that it had disappeared from the Welles Shipman Ward House in South Glastonbury, Connecticut, sometime in the fall of 2011. (Incidentally, Matilda Cone also vanished soon after finishing the needlework piece.) Freaked out at the prospect of purchasing stolen art with a creepy backstory, the dealer promptly contacted the police and returned the piece.

HOW TO DRESS FOR A HEIST

In addition to the Fenwick Bell heist’s timing — remember, Sgt. Hayes says 3 p.m. was shift change — the thieves’ wardrobe is another detail that should give people pause.

Despite what Hollywood would have you believe, thieves don’t drop from the ceiling like Tom Cruise (“Mission Impossible”) or Cirque du Soleil their way through a web of laser beams a la Catherine Zeta-Jones (“Entrapment”). And forget under-the-dark- of-night capers. Art thieves work by day because that’s when museum security systems are disarmed — and college campuses are bustling.

And, unlike Tom and Catherine, art thieves don’t generally favor form-fitting black clothing. A long trenchcoat or baggy pants are far superior to a vinyl catsuit for concealing objects. Better yet, vaguely official-looking coveralls that pass for maintenance uniforms on a busy campus may make concealment completely unnecessary and enable a small group of men to walk off with a 400-pound bell at the change of classes without anyone thinking there’s anything unusual afoot.

In his 2011 book, “Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists,” Amore examines motive across several heists, including the 1972 armed heist at the Worcester Art Museum. On Wednesday, May 17, two thieves, dressed in matching clothing — in this case, blue windbreakers — entered the building in the late afternoon. They took two Gauguins, a Picasso and a Rembrandt, stashing them in a barn at the Picillo Pig Farm in Coventry, Rhode Island, designated a superfund site by the EPA in 1977 for the 10,000 drums of hazardous waste and indeterminate amount of liquid chemicals found on the property.

In the commission of the crime, the thieves made a few mistakes. Both neglected to don their ski masks upon entering the museum. One bragged to two teenage girls in the museum that he was about to rob it.

Additionally, one or the other of the thieves:

- Shot a guard. (They were told not to by their leader, Worcester resident and career criminal Florian “Al” Monday.)

- Cut the Rembrandt from its frame and tossed the frame into a canal. The frame, priceless in its own right, was never recovered.

- Laid one of the Gauguin paintings, “Brooding Woman,” on the getaway car’s roof rack and sped away, securing it by hand; that is, one of the thieves draped his arm over the painting as they fled.

The gang’s biggest mistake, though, was its failure to think through how they would sell the paintings. Monday, the heist’s ringleader — “mastermind” would be a gross overstatement here — eventually led authorities to the pig farm after a rival gang demanded, at gunpoint, that the paintings be turned over to them.

Experts like Amore have a particular term for such criminals: stupid.

Set against the colossal blunder that was the Worcester Art Museum heist, the Fenwick Bell theft 37 years later comes across as the work of seasoned and sartorially correct criminals, unconcerned about potential witnesses. And, with the bell’s location at the top of Linden Lane, in front of O’Kane Hall and close to popular academic building Stein Hall, not to mention Carlin Hall, there would’ve been many witnesses around 3 p.m. on a weekday, says Holy Cross Registrar Patricia Ring.

“I think it would be safe to say hundreds of students could have been passing on their way from or to class around 3 o’clock,” she says.

Moreover, the number of men — the student witness said six — is overkill for a 400-pound bell. Half that number could’ve removed the bell from its base and loaded it on the truck in a matter of minutes, Lower says.

So, if the motive for the theft was neither stunt nor scrap, then it’s worth considering that the thieves had a buyer for the bell, Amore says.

How big a market is there for hot antique bells? Hard to say. But, nearly two years after thieves took the Fenwick Bell, an 1853 Hooper bell of comparable size was stolen from the front yard of a Blackstone, Massachusetts, residence, just 26 miles south of campus.

THE OTHER 1853 HOOPER BELL HEIST

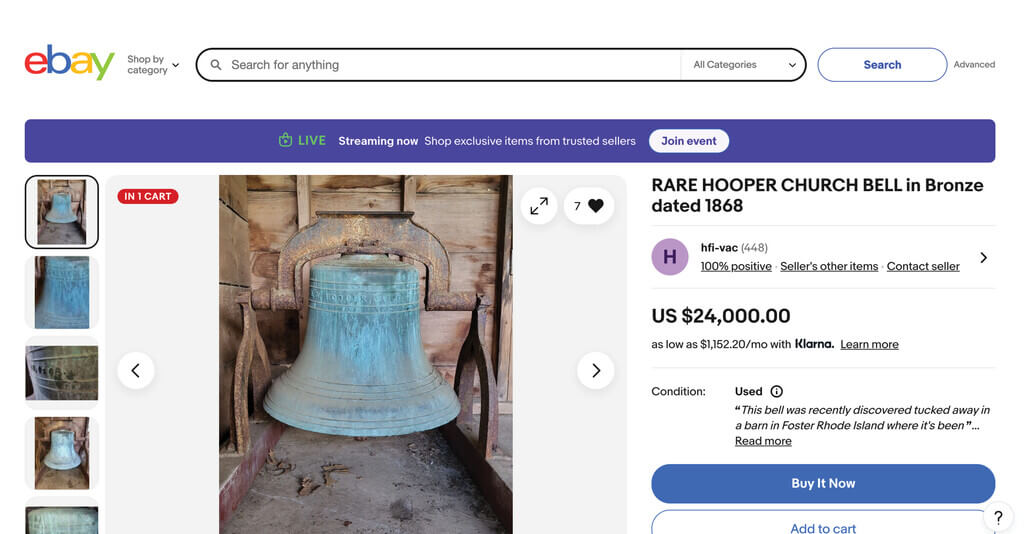

In 2004, the FBI created an art crime team and the National Stolen Art File, whose categories of stolen objects include bells. Holy Cross’ Hooper bell is not in the database. Nor is any other Hooper bell.

But what is established: Bells have been the target of thieves enough times to rate inclusion in the file. And occasionally bells, too, turn up in unexpected places, like an old barn or on eBay. At the time of the writing of this article, eBay was offering an 1868 Henry Hooper bell for sale for $24,000 with this note from the seller: “This bell was recently discovered tucked away in a barn in Foster, Rhode Island, where it’s been stored for 50+ years! It remains in Excellent, ‘As Found’ and untouched condition; no cracks or damage.”

In January 2011, Rhode Island newspaper The Woonsocket Call reported on the theft of a Hooper bell from a Massachusetts man’s front yard. The bell was one of a set, according to the article, “Bell Theft Takes Toll on Owner.” The bell’s owner, Kevin Mahoney, had purchased two bells from his employer, a John Luchetti of Weston, Massachusetts, for $3,000, and secured them to his front lawn with a steel chain. Thieves took bolt cutters to the chain and then took the Hooper bell. The article also notes that several bells were stolen months earlier from a church in Cumberland, Rhode Island. (Those were recovered by police from local recycling centers.)

Calls made to an Attleboro, Massachusetts, phone number identified in the article as Mahoney’s generated an automated response by Verizon saying, “The called party is temporarily unavailable.”

Holy Cross Magazine contacted the Blackstone Police Department, asking if it had an incident report about the 2011 crime. It did.

According to the police report provided by Blackstone Police Chief Gregory Gilmore, on Monday, Jan. 17, 2011, officers took a report for “a past larceny” from a Kevin J. Mahoney. Mahoney said that on Jan. 12, 2011, he’d reported the theft of an “1853 Historical Hooper & Son brass bell” from the yard of a house he owned at 239 Elm St., in Blackstone, Massachusetts. According to the report, Mahoney said the bell weighed approximately 500 pounds and required three men to lift it. He noted he’d purchased the bell for $1,500 six months earlier (which would be approximately June 2010) and discovered the theft when plowing the driveway.

To Chief Gilmore’s knowledge, the bell has not been recovered.

That 2011 Woonsocket Call article also quotes Patrick M. Leehey, research director of the Paul Revere House in Boston, saying that his institution paid $25,000 for a Hooper bell in 1977. Leehey also appears in a file about the Fenwick Bell papers in College archives. In a February 2017 email, he responds to an inquiry by Allison Thiel ’17, who appears to have been working on a project about the bell.

His comments echo those of Lower:

“I have a partial list of Hooper bells compiled by the bell researchers Edward and Evelyn Stickney as a sideline to their main interest, researching Revere bells. I checked their list, and could not find the Holy Cross bell there. Perhaps your bell was stolen before the Stickneys compiled their list, and in any case their list was partial. I am sorry that your Hooper bell was stolen — I hope you get it back some day. Most surviving Hooper bells have the same inscription, ‘CAST BY HENRY N. HOOPER AND CO. BOSTON’ followed by a date.”

A representative from the Paul Revere House says that Leehey retired several years ago, and no one on staff could assist with questions about Hooper bells.

A SECOND MYSTERY

A survey of the March and April 2009 editions of The Crusader for coverage of the bell theft is a rollercoaster ride, expectations-wise, for the amateur bell theft investigator. There is elation upon discovering that the newspaper staff ran a Page 2 public safety blotter in almost every issue. You’ll find a few suspicious person incidents there, but it’s mostly an accounting of building security checks and students needing car batteries jumped, medical attention or escorts to their dorms.

Given the diligent effort to account for all campus incidents, surely, the theft of the Fenwick Bell would be Page 1 news.

But, no. Archives has digitized all available Crusader issues from 2009, and no story about the theft appears. In April 2009, the presumed month of the theft (even that cannot be verified), The Crusader was published on April 3 and 24. The likelihood is that there were only two issues published that month, says Lisa Villa, Holy Cross’ public services and engagement archivist.

“There were no issues of The Crusader published April 10 and April 17,” Villa says. “The volume and numbers flow consecutively from April 3.”

That is, the April 3 issue is Volume 85, number 19, and the April 24 issue is Volume 85, number 20.

Villa posits that Easter and spring break might account for a change in the newspaper’s weekly production schedule. Emails to several members of the 2009 Crusader staff are variations on a theme: “Unfortunately, I do not have any recollection of covering it. Sorry I can’t be of more help. Best of luck.”

Oddly, a review of the Worcester Telegram & Gazette’s 2009 digital records yields not a single article about the crime, either. A public records request to the city of Worcester similarly dead ends: “The City of Worcester has reviewed its files and has determined there are no responsive documents to your request. Unable to locate.”

Calls for information on the College’s social media accounts went unanswered. Absent a campus or Worcester police report, bill of sale, insurance claim or photograph of the bell’s signature markings, there seems to be little else to be said and scant hope of solving the crime.

Except there was a second witness, one whose knowledge of the College was unparalleled. One whose recollections bolster the credibility of that student’s version of events.

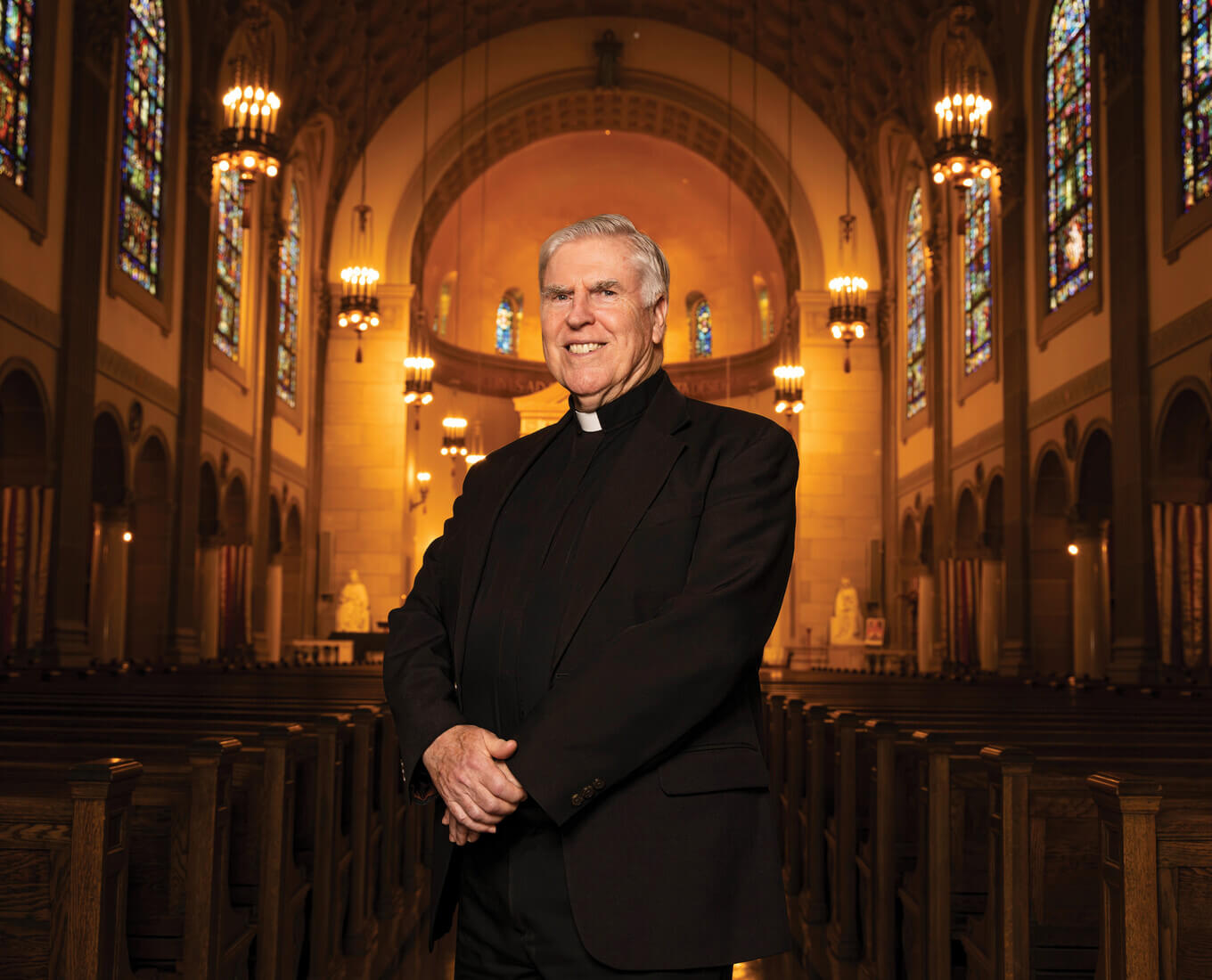

In a cruel plot twist, the other eyewitness to the theft was Holy Cross’ campus historian, the late Rev. Anthony J. “Fr. K” Kuzniewski, S.J., beloved emeritus professor of history and author of the 1999 book “Thy Honored Name: A History of the College of the Holy Cross, 1843–1994.” Fr. K left no written account of the theft that we know of, but he did speak to Holy Cross Archivist Sarah Campbell about what he saw that day.

“He watched as men in coveralls drove up, unscrewed [the bell] from the base and drove it away,” Campbell recalls, shaking her head and half smiling in the rueful way people do when a thing is anything but funny.

“I do not remember exactly what Fr. K said beyond that, but I remember my shock when I walked by the [bell’s] empty cradle later that day. The bell was one of those things you walk by hundreds of times and don’t notice until it’s gone,” Campbell says. “Looking at the empty cradle was quite sad; it hit me the same way as those empty frames on the wall at the Gardner Museum: Something was there that is now gone, and we’ll likely never see it again.”

So what, if anything, remains to be said?

“YOU CAN TAKE THE WORK, BUT ...”

A pearl begins as an irritant. A speck of sand or a parasite finds its way inside an oyster, and the mollusk responds by coating it in nacre, a calcium carbonate substance, and lo and behold, the result is a thing of beauty, a treasure. The theft of the Fenwick Bell is similarly an irritant and a delight. There is something maddening and delicious in an unsolved mystery — as the popularity and proliferation of countless true crime television series, novels and podcasts attest.

James Welu is director emeritus of the Worcester Art Museum and a distinguished visiting lecturer at Holy Cross who teaches courses in museum studies and 17th-century Dutch Art. While the loss of a treasured object is profound, he says, even thieves who get away with it don’t get everything.

“The history behind a work of art, its provenance, as we call it, is part of world history,” he says. “In the case of the Holy Cross bell, the theft is part of its history, too. You can take the work, but you can’t take away its impact on history.”

Since 2017, Tom Cadigan ’02, director of alumni regional and special programs in the College’s Office of Advancement, has conducted popular campus history tours on family weekends, homecomings and reunions. The bell theft is a tour highlight, ranking right up there with the story of the (alleged) exorcism room and the tale of the (true-but-temporary) immurement of Fr. Crowley in Lehy Hall (the latter a true student prank). Occasionally, Cadigan will hear an “I know a guy” story from an alumnus who says he knows of a classmate who braved the 80-foot drop to ring the Fenwick Bell, though no one has claimed to have made their own “victorious ascent to the spires” that The Crusader editors of 1974 claimed was a regular thing. Truth, here, isn’t of consequence, though. The tale’s the thing. And the mystery delights and somehow compensates for what was lost.

Put another way, the bell’s absence gives it permanence — if only in our memory.

“Holy Cross becomes an extension of home for alumni,” Cadigan says. “They always have a fondness, not only for the relationships they forge, but for the physical space, too.

“You spend a lot of time on this campus, and you get to know your neighbors,” he continues. “You get to know your classmates, you get to know faculty — and the physical place takes on an air of nostalgia.”

And you can’t steal that.