Most students who signed up for Professors David Karmon and Cristi Rinklin’s inaugural Maymester in Venice had the same desire: “I want to see it before it sinks.”

This is a popular tourist narrative, along with visions of glittering blown glass, festival revelers in masquerade, canals haunted by ghosts and mythical sea creatures. The city has a romantic, fantastical aura about it, one that the two visual arts professors wanted to inhabit – and investigate.

“Although the romantic stereotype tends to dominate the popular imagination, it’s just one way of understanding Venice,” Karmon explained. “We wanted to challenge our students to think more critically about the city, and to explore how this extraordinary place can make us think differently about the world we live in today.”

Karmon, professor of architectural and urban studies, and Rinklin, professor of studio art, had been looking for a way to promote collaboration among faculty in the visual arts department, as well as combine their mutual interest in environmental studies. They selected Venice as the perfect environment due to prior experiences working in Italy and the nature of the city itself, and from there, the Maymester course was born.

“Venice is a really interesting case study, because it's not only this ancient city that has all of this history, but it's also where the contemporary art world coalesces every year” with architectural, art and film festivals, Rinklin said. “It's just kind of this place where all these things collide, but it's also full of all of these interesting problems and contradictions. … It gives opportunities to center ideas of art and architecture in really exciting ways.”

Art on the go

Understanding Venice started with getting students out of the studio and into the city. For four weeks beginning in late May 2025, almost every morning began with site visits to architectural and historical landmarks, museums, churches and various spots around the city. They started in Piazza San Marco, the traditional arrival point to Venice, and worked outwards until they had covered the entire city – to the point where students became regulars at cafes, found a gym and knew their way around without a map. It was different from how most experience Venice, which Karmon explained is usually just a pit stop on the way to other destinations throughout Italy, one that lasts no more than a few days.

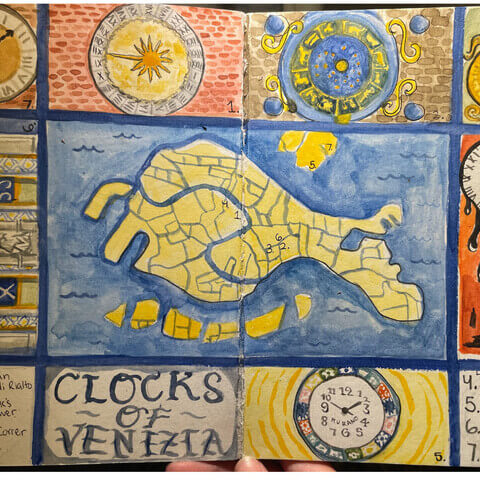

The students also got to know the city on a deeper level – by creating art everywhere they went. They carried a field journal and portable art supplies at all times, to work on projects and to be ready whenever inspiration struck.

This approach to art was a change for Maeve Foley ’26, a studio art and psychology double major, but one she welcomed. “I'm so used to doing all of my art in the studio, but I was sort of surprised at how easy it is to kind of do art everywhere,” she said. “I think it'll make me now think to bring my art supplies with me everywhere I go and want to create art out of everything.”