In high school, Gabriella Bacino '25 and her friends would buy disposable cameras to shoot pictures of one another. There was something different about the older-model cameras and the pictures they produced that appealed to the girls.

"We would constantly capture our lives in grainy color, which got me wondering how the process of developing photos worked," Bacino says. "I have always and am always taking photographs on my phone, but I never felt fully connected to the creation process and the format of my final product."

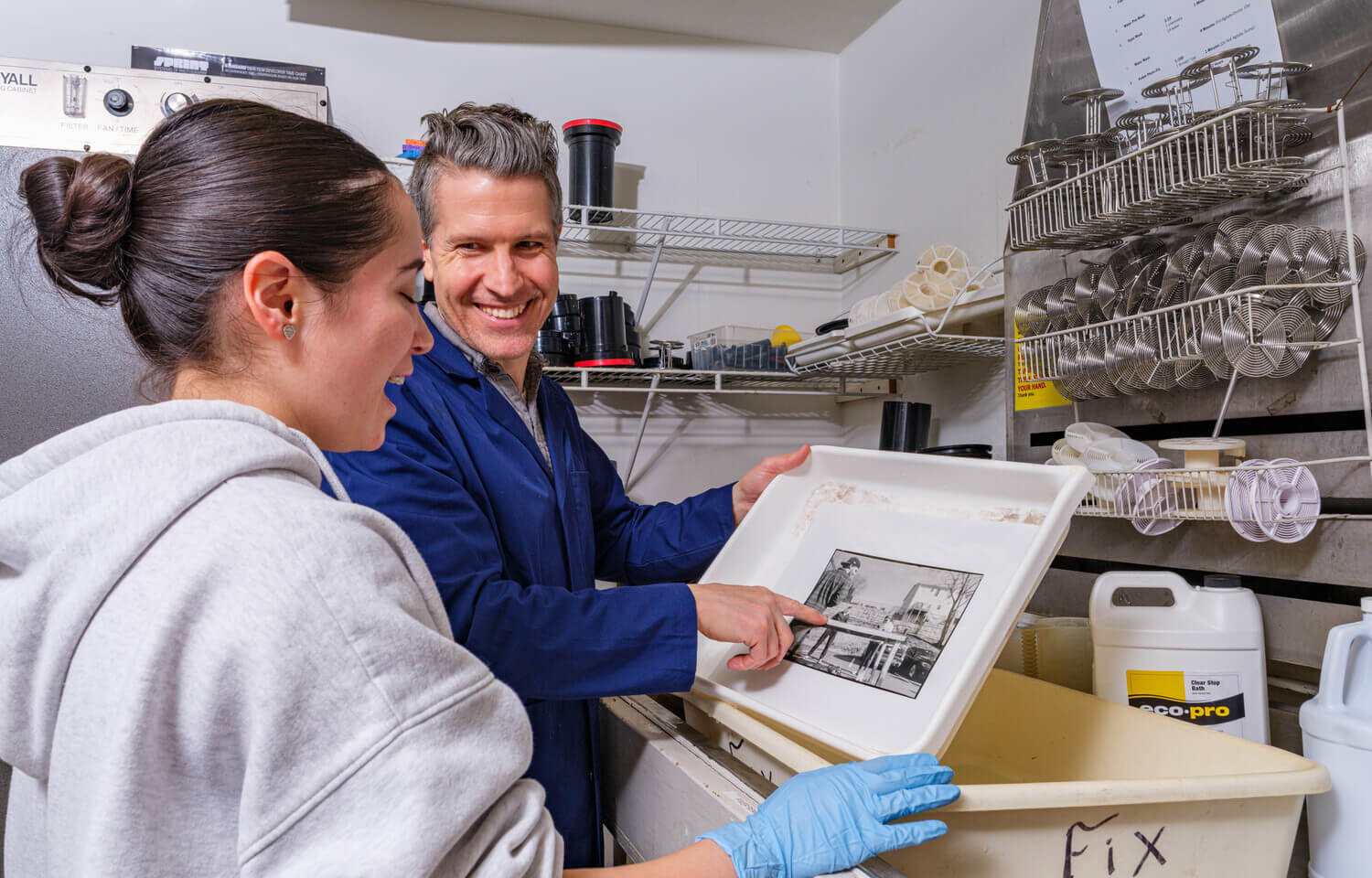

Bacino found connection in Darkroom Photography, a course in which students study analog imaging, using light-based techniques and black-and-white processes in tandem with drawing, painting, and printmaking to create unique images. This hands-on course, taught by Matthew Gamber, associate professor of photography and new media in the visual arts department, is complemented with readings contextualizing photography's evolution as a discipline from its beginnings in the 19th century through the industry's disruption and transformation via digital technology.

Bacino, a philosophy major with a double minor in studio art and creative writing, aspires to work at a fashion magazine one day. She believes the skills she's honed in darkroom photography give her a competitive edge.

"There is so much that goes into developing photos, photograms and chemigrams that it can be hard to remember every change you need to make to get your desired result. We take notes and have signs up to help, but problem-solving can be a tedious process," Bacino says in a subsequent email exchange. "The most rewarding thing is when you finally get it right, when, after an hour of changing time, aperture, and filters, you finally see the changes and details you've been attempting appear in the developer bath."

On dedication to the craft

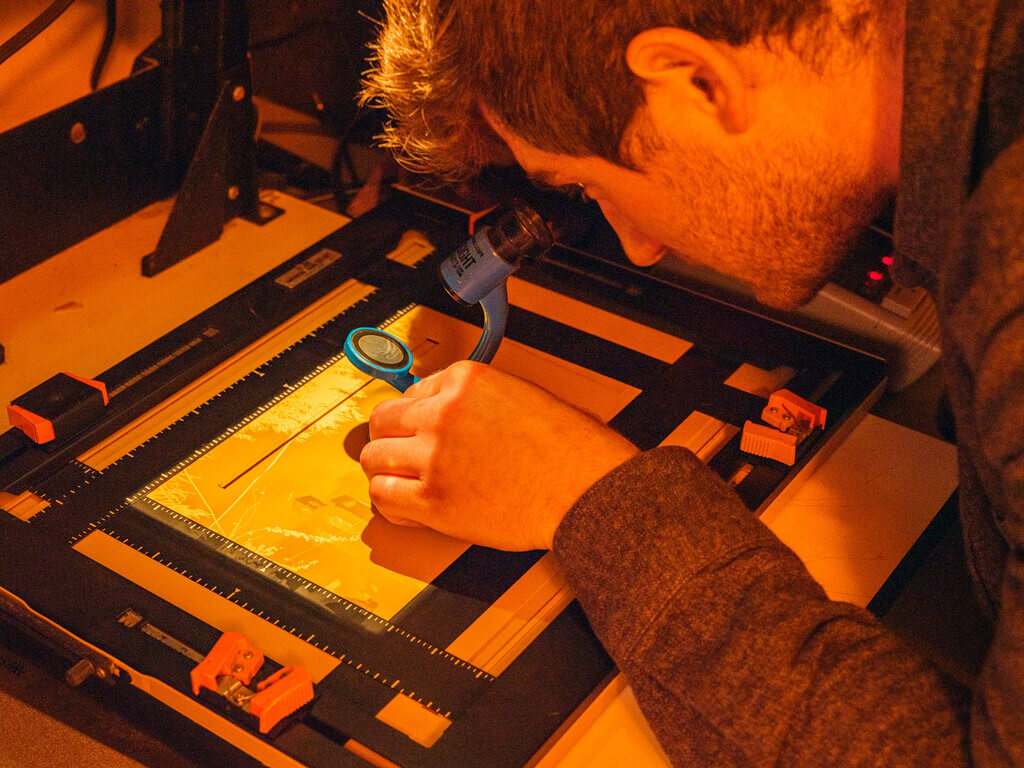

For a generation of digital natives used to smartphones' instant gratification, a darkroom photography course could feel interminably long. And that's fair. This course clocks in at nearly four hours, 5 to 8:45 p.m. Wednesdays. But time flies in the darkroom, says Olivia Montminy '27, an English and studio art double major.

"The most challenging and rewarding parts of this course are the same thing for me: how much time one must dedicate to the craft. You can spend hours shooting film, then you spend at least another hour and a half processing your negatives and letting them dry, and by the time you’ve finished with that, you haven’t even made it into the darkroom," she says.

Montminy is also the photo lab monitor at the Millard Art Center, where the class meets.

"One night I clocked in for work at 5:30 and didn’t leave until almost 10, and all I did was print photos," she exclaims. "But I love those hours I spend there."

Challenging, too, are the topics the course takes up. In Gamber's class, art-making is a politically charged topic for its environmental impact. For instance, a photographer working for National Geographic might visit Prince William Sound, Alaska, to photograph the melting Columbia Glacier as part of a story on climate change. But does the photographer and the magazine bear a responsibility for the ensuing uptick in tourism that can accompany such stories, as people rush to see the thing before it disappears, thus hastening its demise?

Put another way:

"How do I look at my own implication in making this image, for trying to draw other people's attention to it?" Gamber says.

An experience outside the realm of digital devices

Gamber thinks student interest in his darkroom photography course is, in part, a show of resistance to what some may consider the tyranny of technology.

"In this era of Zoom meetings, social media algorithms, deep fakes, and AI, students are more interested in learning film-based photography and traditional darkroom processes," Gamber observes. "Students are grappling with the flood of information on their devices and seek image-making methods beyond smartphones as they try to manage the complexities of consuming media that is not entirely in their control."

Students praised Gamber's teaching and the easy camaraderie that developed as they worked together over the course of the semester.

"This course reminds you how fun it can be to learn and problem solve," Bacino says. "If you love photography but technical or perfect photos are not your style and you want to explore abstraction or see how photography can expand outside of a normal photo, you would enjoy this class. We do so many experiments and try to expand what it means to create a great photo."

And then there are the intangible, unquantifiable rewards that come from immersing yourself in a thing, Montminy says.

"It’s a chance to just put on my headphones and tune out the rest of the world — especially when it’s just me in there," she says. "The darkroom turns into this strange, liminal space where it seems like time passes more slowly and the world falls away. I love it."