In spring 1975, theater legend Arthur Laurents received a Tony Award nomination for directing the revival of "Gypsy," the 1959 classic often referred to as the quintessential Broadway musical. In that same time—and some 200 miles away—David Saint was graduating magna cum laude from Holy Cross, wondering what a career in New York might look like. Fortunately for the American theater, their paths would cross soon enough.

"Arthur was an enormous influence; he had such an amazing sense of who he was," Saint says of Laurents, the late Tonywinning and Oscar-nominated artist who wrote the books (theater parlance for the script) for "West Side Story" and "Gypsy," the screenplay for "The Way We Were," and a host of scripts for other Broadway and Hollywood gems. Laurents, who ultimately became a father figure and mentor to Saint, was also a celebrated director, scoring a Tony for helming the ground-breaking 1983 musical "La Cage aux Folles."

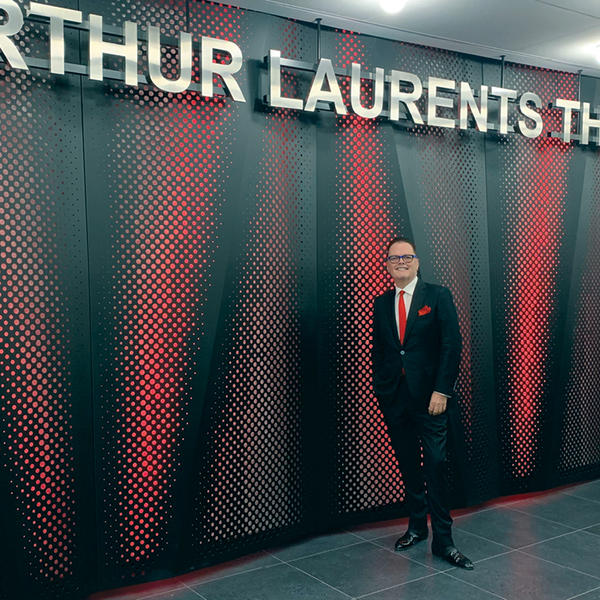

Saint, like Laurents, has also worn a number of hats throughout his career. He's the artistic director of George Street Playhouse in New Jersey, has directed regionally in 36 states, mounted a smash production of "West Side Story" with rotating seating banks in Japan, is literary executor of Laurents' estate and also president of the Laurents/Hatcher Foundation. In a time of crisis for theater, the impact of that foundation is proving more vital than ever.

Providing Critical Aid

Named after Laurents and his partner of 52 years, actor-turned-real estate developer Tom Hatcher, the Laurents/Hatcher Foundation awards an annual prize to an early-career American playwright and also distributes more than $1 million every year in theater development grants across the country. The pair established the foundation in 2010 to support the production of new plays or musicals, a reflection and extension of the career path that launched Laurents to fame.

In March 2020, "The day the theaters closed, we had a show running at George Street and we had another big musical about to start and like everyone we had to pull the plug," Saint remembers. "I was sitting there feeling so helpless, and I thought I've got to do something. And I thought, ‘Wait a minute, I run the foundation!'" From there, Saint phoned the trustees and worked to quickly distribute 30 grants of $25,000 a piece to theaters nationwide.

"It was great to be able to do something and help, and so gratifying to have done something proactive right away," Saint says. "You didn't have to apply for a grant or go through the usual steps; we just gave an emergency gift."

Saint also saw that his own audience community was taken care of, making dozens of calls to donors who gave money to George Street Playhouse despite its stages being dark. "What I learned is how much the theater means to them," Saint says. "They'd say, ‘I have four best friends and I associate my girlfriends with your theater; you always give us something to talk about.' Another woman said, ‘I'm doing well physically, but I'm starving culturally.'"

Six months later, in October, the Laurents/ Hatcher Foundation issued a second round of emergency grants. Theatre news website Broadway World reported that the foundation was "one of the first to respond to the crisis," noting "with this second round of $10,000 grants, the foundation has awarded $875,000 in emergency funding."

Ensuring the Laurents Legacy

As foundation president and literary executor of Laurents' estate, Saint juggles many responsibilities in maintaining the integrity of his friend's name and legendary body of work.

"There's a lot of responsibility and a lot of privilege; I'm both grateful and daunted by the work," Saint says of his executor role. "With someone like Arthur, who was so prolific in so many different mediums, I basically serve as the gatekeeper; I'm the guardian of the estate. If someone wants to do a major production, they have to come to me to get the rights."

That's a legal responsibility, but it's also an artistic one. "You want to make sure a title like ‘West Side Story' or ‘Gypsy' is protected. If you don't take into account what the artistic approach is, you're not really protecting the property," he explains. This often means having approval over a project's director and lead actors.

But before he became a president, executor and director, Saint — gregarious, open and always with his eyes toward the horizon — was back in Worcester, studying English and contemplating his next steps.

"One of the biggest draws for Holy Cross was they had a beautiful theater and an active theater department," Saint notes. "The first month of my four years at Holy Cross, I auditioned and got into one of the plays." He also hails from a family with deep Crusader roots: late father, Paul F. Saint '40, and brothers, the late P. Michael Saint '71, John P. Saint '80 and Joseph R. Saint '88.

He started performing in high school and he kept busy on campus auditioning, rehearsing and performing. "I had the greatest time, I met some wonderful people," he says, crediting, among others, beloved theater professor Don Ilko. He cites several favorite roles from his days performing in Fenwick, but playing the titular role in Molière's "The Miser" his senior year was the pinnacle. "That was an unbelievable experience I'll always remember — even alumni today who were around Holy Cross during those years will say, ‘I'll never forget ‘The Miser,'" he says.

That production was noteworthy in more ways than one.

"Ann Dowd '78 and I acted opposite each other," he says of the Emmywinning actress. "Ann played Mariane in that production. We've stayed in touch and been friends ever since."

This collaboration with high-profile peers sparked a motif in Saint's career: When he meets one of the greats, time and time again they find a way of re-entering his orbit and working alongside him. Years later, Saint would direct Dowd in a reading of a play. But prior to that, Saint pursued another career that often acts as a gateway to directing.

"I went right to New York and auditioned for Uta Hagen," Saint says of the two-time Tony winner who originated the role of Martha in the theater classic "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" She later became a highly influential acting teacher at the Herbert Berghof Studio.

"I just thought, ‘If I get in, I'll move to New York.' I got in, so I moved with $500 in my pocket and I studied with Uta for six years."

Saint didn't only rub elbows with Hagen at the famed HB Studio, he also trained alongside the industry's most renowned artists. "Matthew Broderick, Liza Minnelli, Rock Hudson — it was such a range of people in the class," Saint recalls. "The great thing about that was they were working actors, so they treated the classes like a gym."

Much like with Dowd, Hagen remained a fixture in Saint's life: During his inaugural season at George Street Playhouse, his artistic home of now 23 years, she starred in one of his shows. "I learned a lot about directing from what I learned in Uta's class: the emotional core of a scene," he says.

While enjoying gigs as an actor, Saint saw directing as perhaps a more amenable career, more suited to his interests. "As an actor, you're slightly limited by your age, what you look like, how you come across," he explains. "But as a director, you can explore any role in any play you feel passionate about, so I found I really loved directing."

From there, Saint said his "years were spent in a trunk," with directing jobs more often than not taking him on the road to some of the country's most prestigious regional theaters. "Someone said to me, ‘You have a very schizophrenic career: You're all over the place with your genres,'" as Saint would direct everything from edgy pieces and new plays to comedies and musicals. But that comment, Saint says, "was a compliment to me."

In his early days as a director, he'd do eight or nine shows a year — "I went to wherever the work was," he notes — which included Seattle Repertory Theater, where he'd brush shoulders with Laurents and jumpstart a decadeslong friendship.

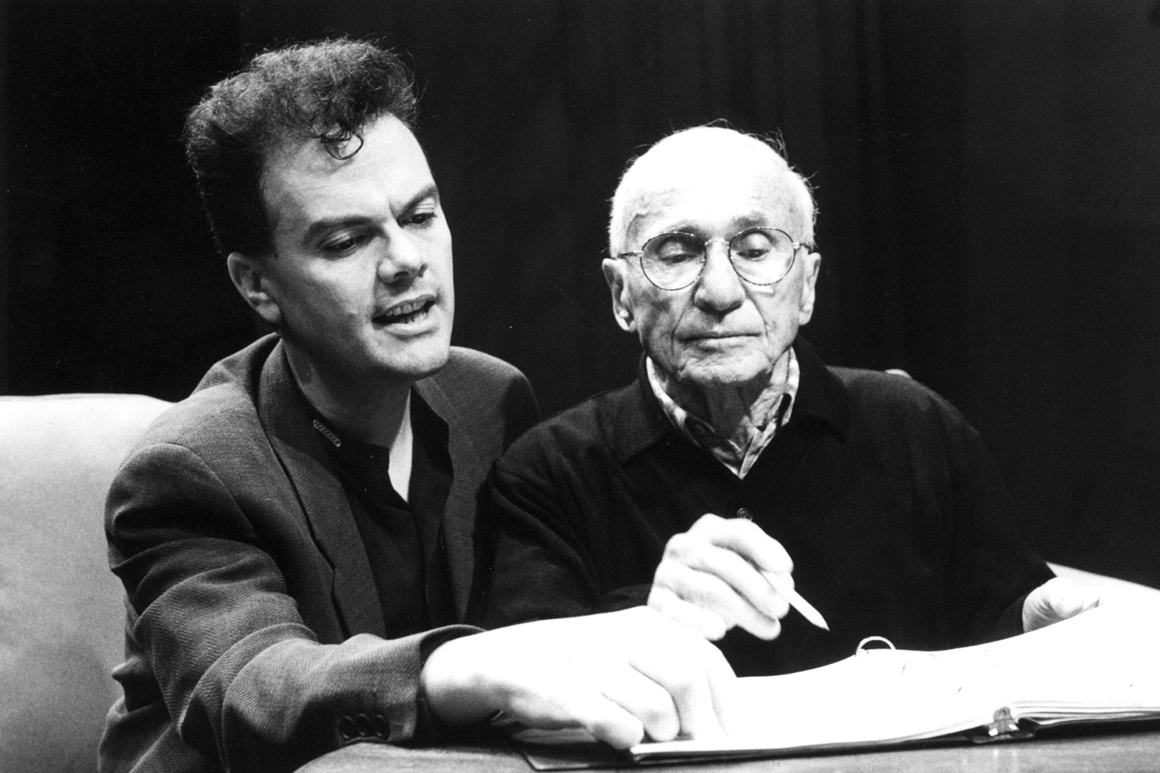

Saint first met Laurents in the early 1990s after directing "After-Play" at Manhattan Theatre Club, a seven-time Pulitzer Prize-winning theater. "Arthur said, ‘You're a good director, you have a real gift for directing high comedy,'" Saint remembers. Months later, he was working at Seattle Rep where Laurents was developing a new work. They ran into each other on the street and went out for drinks; a couple months later, "My agent called and said, ‘We just got a new play by Arthur Laurents and he wants you to direct it.'" From there, the pair would be frequent collaborators until Laurents' death in 2011 at age 93, with Saint directing 11 of his plays.

Laurents' lean, cherished scripts run the gamut, but what seems to unite his characters is a quality Saint also shares: a sense of seeing goals and persevering to attain them despite any obstacle.

"Arthur believed that you have to encapsulate in one sentence what the piece is about," Saint says. "Anything that doesn't serve that, you don't need." Saint describes the thesis for "Gypsy" — a musical chronicling the ultimate stage mother's quest to make her child a star — as the need for recognition. (Saint would assist Laurents on his last Broadway revival of "Gypsy," an awardwinning production he helmed in 2008 at age 90.) For "West Side Story," the north star was "the struggle to love in a world of bigotry and violence," Saint says.

Bringing a Classic to the Screen Once More

The contrast of passion and intolerance has made "West Side Story" one of the most enduring stories of the past half century (it debuted on Broadway in 1957), with multiple productions on Broadway and a 1961 movie adaptation winning the Academy Award for Best Picture. Saint is intimately familiar with the landmark musical, having worked as associate director on the Laurents-led 2009 Broadway revival. He also helmed national tours and in 2019 created his own technically dazzling production in Japan with audience seating that revolved around the set.

While directing the Japan production, "couples would come up to me and say, ‘This is our story. We grew up in rival feuding villages and our parents wouldn't even let us date, let alone marry,'" Saint says. "The musical has a universality. I don't care if ‘West Side Story' takes place on the moon, or if one gang is pink and one is blue: It's about racial bigotry and violence, and then a love story in the middle of it. Unfortunately, that narrative hasn't changed."

In 2019, Saint found himself working on the musical again, but this time behind the camera, playing a key role in the much-anticipated new movie adaptation directed by Steven Spielberg. Originally slated for a December 2020 release, the movie's debut was moved to December 2021 due to the pandemic.

Saint's collaboration with Laurents made him an invaluable presence on set, recalling Spielberg telling him, "I want to hear everything you have to say. You are my direct link to Laurents' work."

"Originally my role was to work with Tony Kushner on [the movie script]," Saint notes. But he also had two requests from Laurents rolling around in his head. "Arthur had told me to not let a theater director direct it. He wrote a lot of movies, and he said he knew enough to know they are two different mediums. It needs to be a cinematic genius," Saint says. "The second thing is whoever they get to work the screenplay needs to be someone very smart — and please be there with them."

Check and check: With Spielberg and Kushner, two of the greatest directors and writers of their generation, Laurents' sacred material was in good hands. Saint's contribution and work earned him the title of associate producer on the film.

"When they started shooting, I thought I'd go a few times," Saint says. "I got a call from Steven's associate who said, ‘Listen, Steven loved talking with you on the set today: He would like you there as much as possible,' so I went almost every day! I'd sit there with him; I have to say, he's a genius, of course, but the thing that most surprised me was how humble and generous he is."

The Road Ahead

With "West Side Story" complete, Saint returned to his theater in New Jersey where he — like others in the industry worldwide — eagerly await the day audiences can gather again for a shared live experience. Until that time, tens of thousands of theater professionals are left without an income, and billions of dollars generated by theater are being lost in cities large and small worldwide. The Broadway League notes that in New York City alone, the theater industry supports more than 96,000 local jobs, everyone from shop owners to taxi drivers and restaurant owners; the city is losing billions in tourism revenue, largely propelled by Broadway audiences.

The pain of the current moment, with theaters closed for nearly a full year, is a "double whammy" for performers, Saint says: "It's not just the no paycheck coming in — it's also the ‘I don't have a rehearsal room to go to, to do what I love.'"

"I would urge people to remember the artists in their lives, even if you just reach out or encourage them," he advises. "Nonprofit theaters depend on their audiences and support; reach out whenever possible and give a donation or a letter to remind them of how important they are to you."

Written by Billy McEntee for the Winter 2021 issue of Holy Cross Magazine.

About Holy Cross Magazine

Holy Cross Magazine (HCM) is the quarterly alumni publication of the College of the Holy Cross. The award-winning publication is mailed to alumni and friends of the College and includes intriguing profiles, make-you-think features, alumni news, exclusive photos and more. Visit magazine.holycross.edu/about to contact HCM, submit alumni class notes, milestones, or letters to the editor.