Some would say poetry is the calculus of English: Difficult. Inscrutable. Maddening. An art form intended for a small, select and stuffy society that measures words by the foot and speaks the strange and secret language of caesura and catalexis, stanza and scansion.

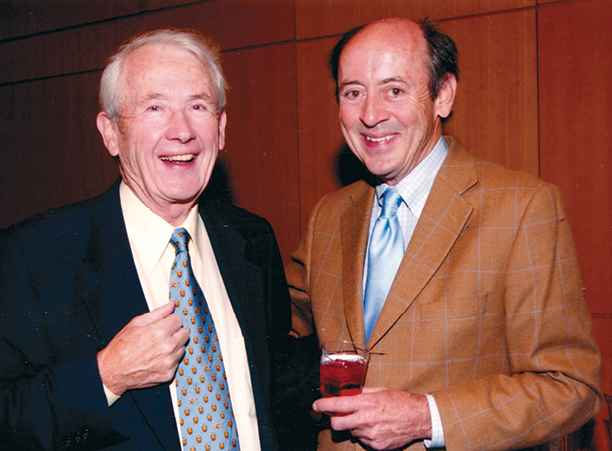

Fans of poet Billy Collins '63 Hon. '02 don't have those issues. They will tell you that his poetry is a journey from the familiar to the sublime, culminating in a moment of truth so, "Yes, exactly!" that you grin in recognition, unanimity and, always, wonder. With author Frank McCourt.

With author Frank McCourt.

And about those fans: The former U.S. Poet Laureate has won a large and loyal following over his career, one that includes former President Barack Obama, rock stars, actors, famous novelists, a Beatle and, yes, even teenagers, by being the champion of the everyday experience, a poet whose work throws open the door and waves you in.

"I want a poem to feel invitational, hospitable," Collins says. "The first few lines should contain something easy to accept, something that makes few demands. Then you can close the door behind the reader and get wiggy."

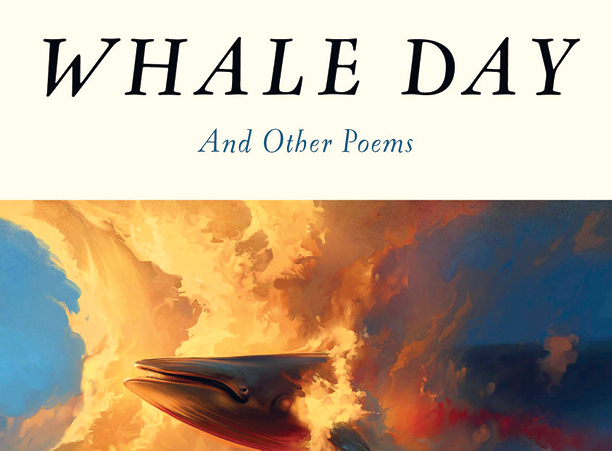

At the end of September, Random House will publish Collins' 14th book of poetry, titled "Whale Day." His last two collections, "Aimless Love" and "The Rain in Portugal," made The New York Times' bestseller list. The Wall Street Journal has called Collins "America's favorite poet." The Boston Globe has said that Collins is a "sort of poet not seen since Robert Frost." Literary lion John Updike once waxed, "Billy Collins writes lovely poems… Limpid, gently and consistently startling, more serious than they seem, they describe worlds that are and were and some others as well."

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Annie Proulx stakes claim for all of us: "I have never before felt possessive about a poet, but I am fiercely glad that Billy Collins is ours," she says.

Collins' greatest contribution to poetry, however, may never earn him an award. It isn't calculable. Poetry reading in the United States is on the rise and the greatest growth in readership has been among 18-to-34-year-olds, according to a survey by the National Endowment for the Arts. This would be the generation that benefitted from Poetry 180, Collins' project with the Library of Congress, which has offered a daily dose of poetry to the nation's high schools since 2001. To be clear, the project doesn't offer a daily dose of Collins. Rather, it features the work of a whole army of poets selected by Collins for writing poetry that is understandable, illuminating — even painless. Factor in that 19 years later, everyone, it seems, is displaying their verse — on paper and in performance halls, on social media platforms and at hip-hop concerts. Poetry is having a big moment, so big that, in 2018, The Atlantic crowed "Poetry is Everywhere," noting that "Far from 'going extinct,' as it was once predicted, poems are viral, vital — and invincible."

Poetry is cool again, and Billy Collins is one of one of the people we have to thank for that.

We begin with a poem whose title is one of several that are routinely shouted, yes, shouted, at Collins' readings, usually by someone with the zeal a concertgoer has for their favorite song.

The Lanyard

The other day I was ricocheting slowly

off the blue walls of this room,

moving as if underwater from typewriter to piano,

from bookshelf to an envelope lying on the floor,

when I found myself in the L section of the dictionary

where my eyes fell upon the word lanyard.

No cookie nibbled by a French novelist

could send one into the past more suddenly—

a past where I sat at a workbench at a camp

by a deep Adirondack lake

learning how to braid long thin plastic strips

into a lanyard, a gift for my mother.

I had never seen anyone use a lanyard

or wear one, if that's what you did with them,

but that did not keep me from crossing

strand over strand again and again

until I had made a boxy

red and white lanyard for my mother.

She gave me life and milk from her breasts,

and I gave her a lanyard.

She nursed me in many a sick room,

lifted spoons of medicine to my lips,

laid cold face-cloths on my forehead,

and then led me out into the airy light

and taught me to walk and swim,

and I, in turn, presented her with a lanyard.

Here are thousands of meals, she said,

and here is clothing and a good education.

And here is your lanyard, I replied,

which I made with a little help from a counselor.

Here is a breathing body and a beating heart,

strong legs, bones and teeth,

and two clear eyes to read the world, she whispered,

and here, I said, is the lanyard I made at camp.

And here, I wish to say to her now,

is a smaller gift—not the worn truth

that you can never repay your mother,

but the rueful admission that when she took

the two-tone lanyard from my hand,

I was as sure as a boy could be

that this useless, worthless thing I wove

out of boredom would be enough to make us even.

—From "The Trouble With Poetry And Other Poems"

If you haven't been to one, know that the traditional poetry reading is a solemn affair. The poet reads a selection of poems, the audience applauds politely, questions follow and a book signing concludes the event. There's often seating for about 10 or 50 more attendees than are present. A Billy Collins poetry reading is more like a rock concert: sold out, standing room only, requests shouted, thunderous applause, standing ovations. In fact, Collins may be the only poet ever to have toured with a rock star (Grammy-winner Aimee Mann). And he's also likely the only poet who can claim that he has opened for Dave Brubeck and been introduced by Carly Simon and Bill Murray.

What makes Collins such a draw? Well, his poems are often laugh-out-loud funny even as they tackle themes typically enshrined in solemnity: death, loss, loneliness, joy, hell, faith. Cats, dogs, mice (lots), birds and cows are well represented, too. Really any topic is fair game. And, yes, there are those poems whose titles signal familiar poetical terrain: "The Music of the Spheres," "Cosmology" and "The Death of the Allegory," but then there are others that deliver on their titular promise of hilarity: "Ode to a Desk Lamp," "Keats: Or How I Got My Negative Capability Back," "Victoria's Secret" (yes, the catalog), "Lucky Bastards" and "More Than a Woman" (in which the speaker suffers a Bee Gees earworm).

Credit to Collins' parents here. From the time he was a toddler, Collins' mother read to him, "Black Beauty" and "The Yearling," and recited Shakespeare. And his father had a wicked sense of humor and brought home copies of "Poetry" magazine when Collins was a teenager.

"My mother had these two voices: her regular speaking voice and her poetry voice, and I've compared it to AM and FM radio. The poetry voice was the FM," Collins says. "And I could tell there was a different sound coming out of my mother's mouth and it sounded, well, someone said, 'Poetry is language that means more and sounds better,' and this clearly meant more and sounded better than regular talk."

Collins' father, William, made art of the practical joke. He once had an exact copy of a co-worker's hat made a size larger than the original so that he could watch the man's consternation at the misperception that his head was expanding or shrinking. "Like, Monday through Thursday, he would put the real one out, his original hat," Collins says, "and then Friday he slipped the big one in. That's real dedication."

It's the foundation for another of Collins' most popular poems, "The Death of the Hat." That and "The Lanyard" are elegies, but in classic Collins fashion they start with the everyday and end in the sacred. It's a hallmark move.

"When I wrote 'The Lanyard,' I wasn't really thinking of my mother. I was thinking of the lanyard. I was thinking of camp, and I thought I'd write about camp. And then, as I wrote, it became a poem about my mother. The other poem, 'The Death of the Hat,' became about my father," Collins says. "Notice that the hat and the lanyard serve as portals or doorways to the larger subject of my mother and father. I could never write 'elegy' on the top of a poem about my father. It's too big a subject, but he was able to slide into the hat poem and my mother slipped into the lanyard poem."

Lest it all sound a little too literary, Collins, who watched a lot of Looney Tunes in his youth, also calls Bugs Bunny "a major influence."

Books

From the heart of this dark, evacuated campus

I can hear the library humming in the night,

a choir of authors murmuring inside their books

along the unlit, alphabetical shelves,

Giovanni Pontano next to Pope, Dumas next to his son,

each one stitched into his own private coat,

together forming a low, gigantic chord of language.

I pictured a figure in the act of reading,

shoes on a desk, head tilted into the wind of a book,

a man in two worlds, holding the rope of his tie

as the suicide of lovers saturates a page,

or lighting a cigarette in the middle of a theorem.

He moves from paragraph to paragraph

as if touring a house of endless, panelled rooms.

I hear the voice of my mother reading to me

from a chair facing the bed, books about horses and dogs,

and inside her voice lie other distant sounds,

the horrors of a stable ablaze in the night,

a bark that is moving toward the brink of speech.

I watch myself building bookshelves in college, walls within walls,

as rain soaks New England,

or standing in a book store in a trench coat.

I see all of us reading away from ourselves,

straining in circles of light to find more light

until the line of words becomes a trail of crumbs

that we follow across a page of fresh snow;

when evening is shadowing the forest

and small birds flutter down to consume the crumbs,

we have to listen hard to hear the voices

of the boy and his sister receding into the woods.

—From "The Apple That Astonished Paris"

Holy Cross, 1953: The Rules

• No skipping 7 a.m. Mass.

• No lights after 10 p.m.

• No drinking in the rooms.

• No women in the rooms.

• No cars on or off campus.

• No jacket + no tie = no Kimball.

It was like a 19th-century English boarding school, says Collins' friend John Whalen '63. But things were happening. The civil rights movement was gaining ground, and in 1960, the country had its first Catholic president. And there was this small contingent of guys, the New Yorkers, who were different, aware, Whalen says: "You could feel some change in the air, but it hadn't arrived yet. It was anticipatory." Whalen, a Vermonter, gravitated to the New Yorkers.

"Collins was one of the New York guys, and they were hip, so I threw in with them right away. With Collins everything was ironic and cool," Whalen says.

Whalen, who inspired not one, but two of Collins' poems: "Looking for a Friend in a Crowd of Arriving Passengers: A Sonnet" and "The Country," says their near-60-year friendship has its foundation in laughter, jazz, adventure and a shared devotion to language.

"It was like 'A Hard Day's Night': all comic and light and hilarious. And Collins just had that great sense of language," Whalen says. "He had such a sense of humor with The Purple when he was the editor. Collins mentioned Robert Frost being at Holy Cross, right? That was a thrilling thing, like Mick Jagger coming."

Whalen's reaction to Frost's cameo may not have been typical. The campus in its entirety didn't fully embrace poetry, Collins observes.

"The Purple would come out on a certain day, and it would be stuffed in all the mailboxes. And we editors would go down to Kimball and watch people throw them into the wastebasket, you know, with the other junk mail," Collins observes. "And, of course, we would fetch them out of the wastebasket."

Wait for it.

"But that just reinforced our sense that we were a special group, we were the literary, sophisticated group, and these Philistines just didn't know what they were doing," Collins deadpans. "So, great." Purple editor Collins with the late Bernie Schmidt "63 and Tony Libby '63.

About that time he met Frost:

"It was 1960, only a few years before he died. I was editor of The Purple, and the staff and I were invited to a luncheon with Frost," Collins says. "We were 'encouraged' not to talk. So there were the two Jesuits sitting next to Frost and Dr. Callahan. Nobody said a word. We just kept our noses in our soup. Frankly, the immensity of the experience didn't dawn on us till later. We were focused on eating good food for a change. Then we went to his reading.

"We had Frost and Auden visit while I was there," Collins notes. Silence follows at the shared wonder of that.

The other momentous event in the life of student William J. Collins involves a sly meditation on a flea.

"Mr. Francis Drumm was rather short, wore wire spectacles and always dressed in a three-piece suit with a watch fob — completely turned out. He taught 17th-century poetry — all the metaphysical poets," Collins recalls. "We really admired him, but there'd be a number of examinations during the semester, and he had the unique habit of not announcing them.

"We would station someone at the door and if he were carrying a pile of blue books, that was the giveaway. People would literally jump out the windows — this was on the first floor of Wheeler — and we'd just wiggle out the window and into the shrubs, then get over to the infirmary complaining of a sore throat or stomach ache.

"Anyway, he was a wonderful teacher, and I guess I had a, you'd call it an epiphanic — which is my favorite adjective, by the way — an epiphanic moment connected to his class when we read John Donne's 'The Flea.' It was the first time I experienced genuine literary jealousy. I was so angered that I didn't write that poem and fantasized that I did."

It would be almost two decades before Collins' career as a poet took off. He confided to John Whalen that he didn't think publication, let alone international recognition, literary prizes and six-figure book deals, was in his future. He became a faculty member at Lehman College of the City University of New York. Then came the kind of hopeful encouragement that poets dream of: Famed editor and former President Bill Clinton's inaugural poet Miller Williams returned a manuscript to Collins with 17 poems separated from the rest. Produce more like the 17 here, Williams wrote, and Collins would have his book deal. The result was the 1988 publication of "The Apple That Astonished Paris," the book Collins calls his "first real book of poems."

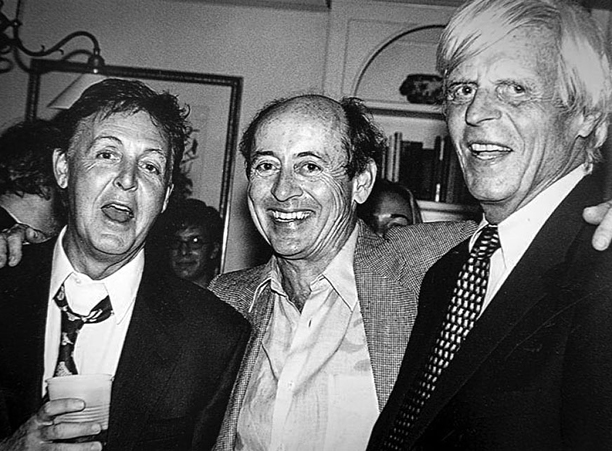

"Williams' words were more encouragement than I had ever gotten before and more than enough to inspire me to begin taking my writing more seriously than I had before," Collins says. A year later, Random House offered Collins an unprecedented six-figure deal for three books. Two years later, in 2001, Collins was named U.S. Poet Laureate. And John Whalen? He found himself celebrating his friend's success at George Plimpton's townhouse alongside some of Collins' friends, notably Paul Simon and Sir Paul McCartney.

"It was exciting, and he was so generous about it," Whalen recalls. "He's exactly the same person, you know. He didn't lose his old friends or anything. He brought you along."

********

From the final stanza of "The Names," read in front of a special joint session of the U.S. Congress on the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks:

Names etched on the head of a pin.

One name spanning a bridge, another undergoing a tunnel.

A blue name needled into the skin.

Names of citizens, workers, mothers and fathers,

The bright-eyed daughter, the quick son.

Alphabet of names in green rows in a field.

Names in the small tracks of birds.

Names lifted from a hat

Or balanced on the tip of the tongue.

Names wheeled into the dim warehouse of memory.

So many names, there is barely room on the walls of the heart.

A traditional elegy is a balm, acknowledging mourners' sorrow, showing admiration for the deceased, offering solace. On the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, the Library of Congress asked Collins for a poem. How to memorialize 2,977 people? How to address a nation's sorrow?

Ever the people's poet, Collins wrote "The Names," which includes 25 victims' names, one surname for every letter of the alphabet save X — "(let X stand, if it can, for the ones unfound)." Abstraction and political or mythic language are intentionally absent, Collins told "Wild" author Cheryl Strayed on her podcast, "Sugar Calling."

Instead, Collins chose imagery: "It was picture language, as Emerson calls it. It was the language of the world, of rain, and windows and reality."

In cohering the victims' names with the natural world, Collins had made their number personal and their lives, mythic.

********

So odd to suddenly become subject matter

then have some Sarah fail to identify you on a test

or be analyzed in an essay by young Kyle

who is on to you and your obsession with sex.

It's enough to make us forget where poems begin,

maybe in the upstairs room of an anonymous boy,

his face illuminated by lamplight.

He has penciled some lines in a notebook,

and now he pauses to think up a strange and beautiful title

while the windows of his parents' house fill with falling leaves.

—excerpt from "Mister Shakespeare," "The Rain in Portugal"

Collins' papers are housed at The University of Texas at Austin's Harry Ransom Center. Thus far, the collection comprises 96 document boxes, two oversize boxes, 15 folders, four computer disks and a laptop. Collins' agent and friend, Chris Calhoun, arranged the acquisition. As is the case with Whalen, Collins' friendship with Calhoun spans decades; they met at a poker game in 1981. "At the time, I was a salesman for a tennis magazine and Billy had a shoebox full of rejections," Calhoun jokes.

The Ransom Center is one of the most prestigious institutions of its kind —its collection includes a copy of the Gutenberg Bible. The acquisition ensures that there will be Collins scholars in the way there are Samuel Beckett, James Tate and Arthur Miller scholars: People who devote their lives to the study of a single literary figure.

What one thing would Collins like those future generations of scholars to know? That the accolades and the fame were never part of the plan. That the first 20 years of his professional life were spent happily teaching poetry in the Bronx to students who spoke English as their second language. That he was first a teacher and then a poet. That he kept his head down, wrote on the side and wasn't part of any poetry scene. That back in the day, he had to crash Paris Review parties. "I was on the sidelines, not even really in the game," Collins recalls.

When fame hit, though, he realized his audience had been waiting for poetry that "didn't seem to be, on the surface, completely egocentric and that showed some kind of hospitality to the reader. And that hospitality might be, you know, about the Jesuits and my parents having a kind of respect for people," Collins says. "And I think that respect — as a virtue in life — I think that might've kind of carried over into my poetry voice." Collins with Sir Paul McCartney and Paris Review founder George Plimpton.

Collins with Sir Paul McCartney and Paris Review founder George Plimpton.

An excerpt from George Plimpton's last Paris Review interview, "Billy Collins, The Art of Poetry No. 83," in which he asks Collins about what epiphanies come from looking at the poems aggregated in his collections.

[PLIMPTON] When you look back at old poems in making these selections, do you see any similarities or find things in poems that you hadn't noticed before?

COLLINS Only one thing: I have a lot of mice in my poems.

[PLIMPTON] Mice?

COLLINS That's the only revelation. There are mice all over the place. Still from Collins" daily Poetry Broadcast, in this episode wearing a sweatshirt from his teaching home for over 40 years. Aired live on Facebook from his home study, Collins talks jazz and reads poetry - his and others'. He began the project this spring while spending more time at home due to the pandemic.

When COVID-19 required Americans to shelter in place, Collins once again used the opportunity to democratize poetry, broadcasting daily Facebook readings from his Florida study with wife, Suzannah, acting as director, producer, lighting designer and makeup artist.

"I do my own hair," Collins says.

Viewership keeps growing. Fans hail from exotic locales: Egypt; Donegal, Ireland; Belgium; Inverness, Scotland; and Grinnell, Iowa. And, as is his habit, Collins covers other poets' work in addition to his own, doing his part to keep poetry viral, vital and invincible.

A viewer's comment has inspired a new poem, "The Minor Third," which Collins reads one day and then another, after revising, delighting his audience who bliss out in thumbs up and heart emojis at his providing them this window into his process. That Collins has made a poem of a drive-by comment raises the question, can he make a poem of anything?

"Well, at around 9 this morning our cat Francis — we named him after the pope — caught a lizard and bit its tail off," Collins says. "And the body, unaware, runs away and the tail is jumping all over the place. I could make that into something: two parts of a gecko moving in two directions like a break-up or a bad romance …

"You know, I need to write that down."

Written by Marybeth Reilly-McGreen '89 for the Summer 2020 issue of Holy Cross Magazine.

About Holy Cross Magazine

Holy Cross Magazine (HCM) is the quarterly alumni publication of the College of the Holy Cross. The award-winning publication is mailed to alumni and friends of the College and includes intriguing profiles, make-you-think features, alumni news, exclusive photos and more. Visit magazine.holycross.edu/about to contact HCM, submit alumni class notes, milestones, or letters to the editor.

Billy Collins '63: The Making of an American Poet

The environs of the Holy Cross alumnus and former U.S. Poet Laureate may have changed dramatically, but he hasn't