If St. Joseph Memorial Chapel is the spiritual heart of Holy Cross, Dinand Library is the College’s intellectual equal — a sentiment captured in a 1927 Boston Herald editorial praising the library’s opening that fall:

“The college has created for itself in this new building a center for the intellectual life of its students and faculty as excellent to its own purpose as the chapel on the Mount is to its service as center of the religious life of the college.”

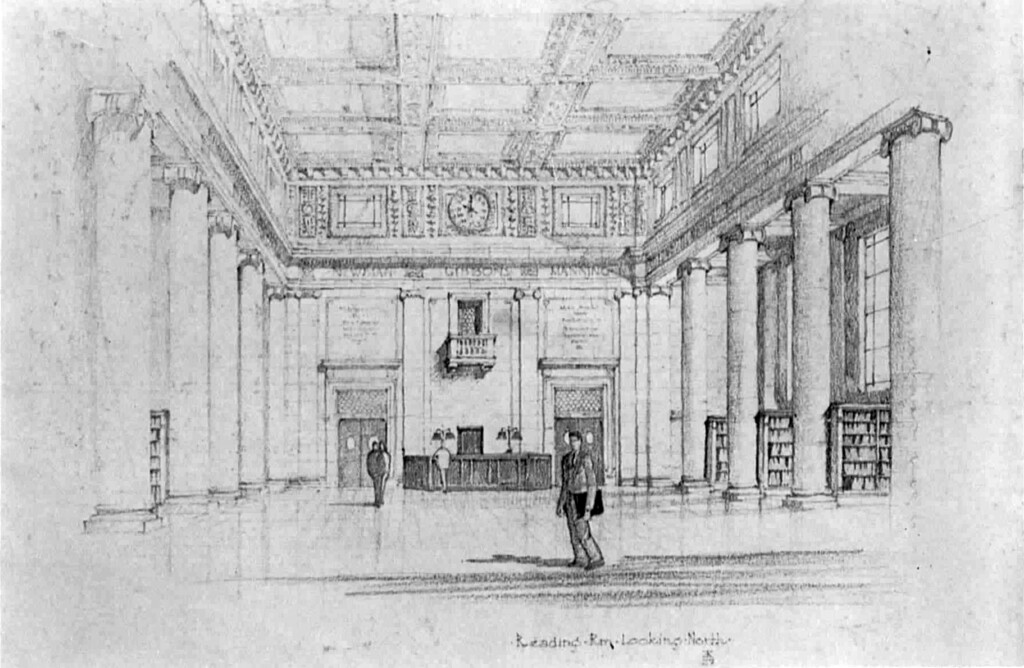

The library’s unveiling marked the triumphant finale of an ambitious undertaking led by then-President Rev. Joseph N. Dinand, S.J., who ultimately transformed a small circulating library located in two rooms in Beaven Hall into an architectural and scholastic jewel on Mount St. James.

“Within three years of its dedication, a distinguished American educator and librarian hailed the Dinand Library as one of the ten greatest college libraries in America,” wrote Irving T. McDonald, Dinand librarian, in 1933. He noted, however, “The library itself advances no such claim. It does not aspire to comparison. It would like to be most useful, and a most memorable source of enrichment to those whom it is privileged to serve.”

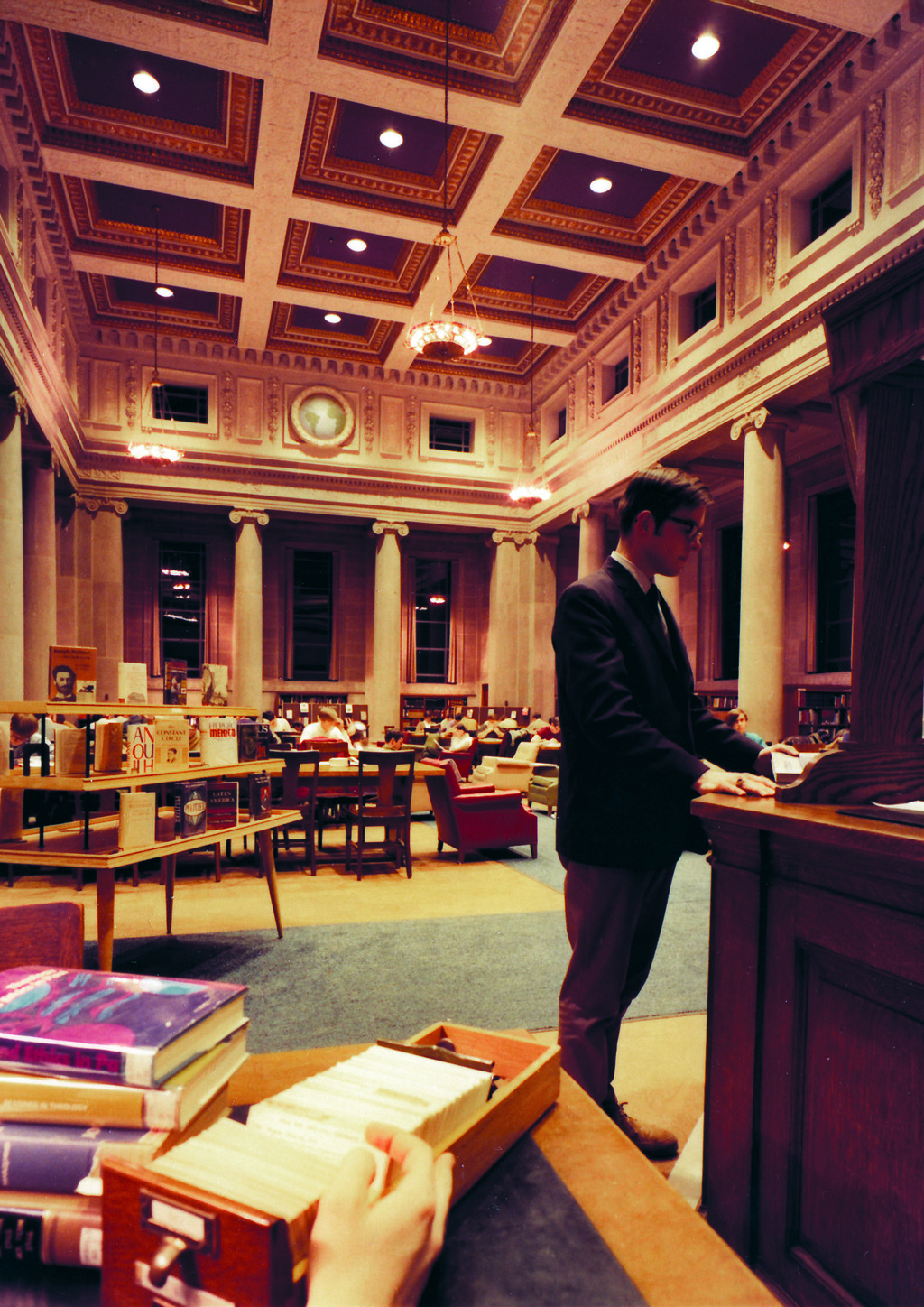

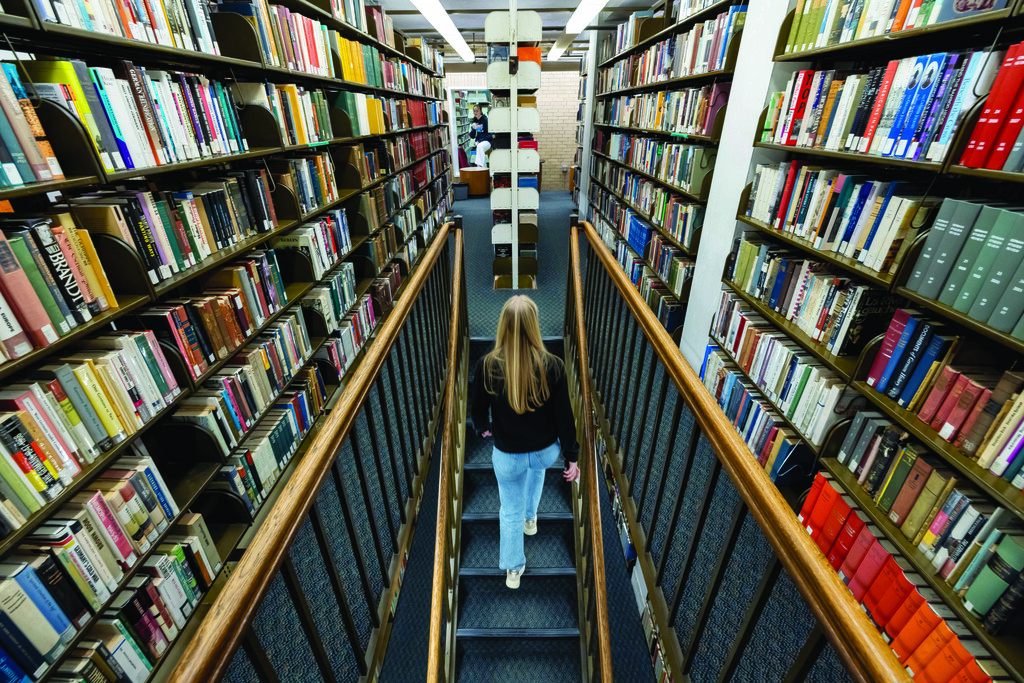

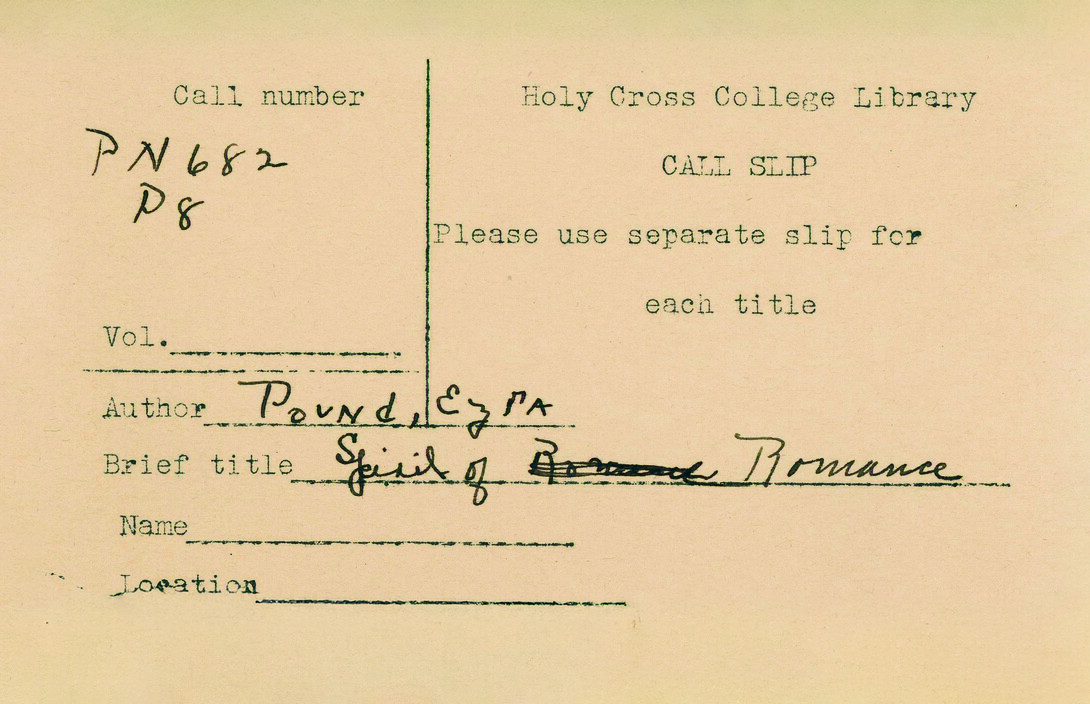

In the nine decades following its opening, the library has done just that, enriching the minds of generations under the hushed glow of reading room lamps and within the (mostly) quiet alcoves of its thoughtfully curated spaces. With insights from the College’s Archives & Distinctive Collections team, who call Dinand’s third floor home, we reveal some lesser-known history and features of this beloved edifice of knowledge.