It was Spring 1987 and high school senior Arnold Principal was lost.

He arrived on Mount St. James for a campus visit, got separated from his host and unknowingly stumbled upon the Black Student Union-sponsored Spring Talent Show.

"Two BSU members immediately recognized that I was not a current student and seemed lost," he remembers. "That night, they made sure I had a great time at the event and hosted me in their dorm. Not only did I join the BSU that fall, but I also performed twice in the talent show the following spring."

Today a proud alumnus of the class of 1991, Principal recognizes the impact of that happy accident and how it changed his life: "I credit coming to Holy Cross to its students and that one particular event." Changing lives, taking action, finding lost students (usually figuratively, but in this case, literally) — and inviting them into a welcoming community of shared experience is a common thread that spans the history of the BSU, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2018.

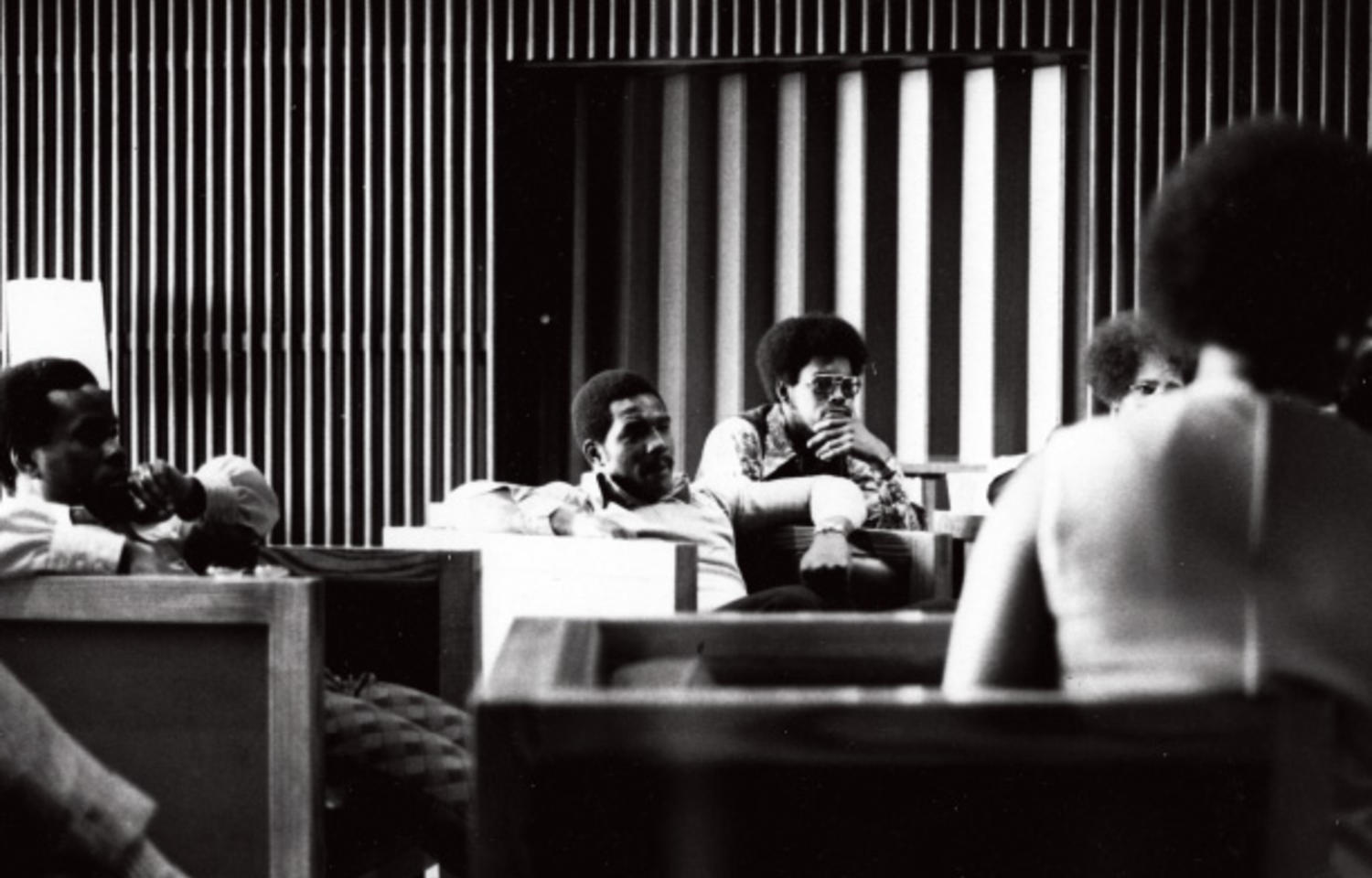

A Place to Find Community

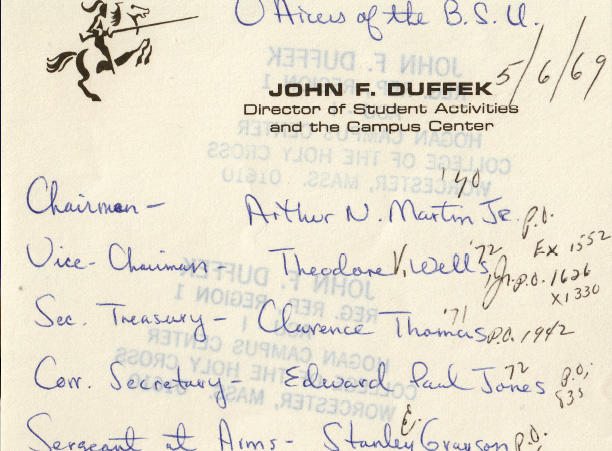

"Prior to 1968, there were very few black students on campus," notes Arthur "Art" Martin Jr. '70, first BSU president. He arrived on campus in 1966, one of two black students in a freshman class of 600. "You may have had eight to 10 black students, so there wasn't any organization or safety net for the number of students who came on board."

In the wake of the April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. John E. Brooks, S.J., '49, then academic vice president and dean of the College, took his now-famous road trip up and down the East Coast to recruit more students of color, an effort to better diversify the student body. That fall, 19 black students arrived at Holy Cross, and while they greatly bolstered the minority numbers on campus, they were still a tiny percentage of a nearly all-white institution, which was jarring for many of them — and their new classmates.

"As much as the black students didn't know the white students, the white students didn't know the black students," Martin says. "There were a lot of cultural differences going on back then, even down to the music that people listened to, the way people danced. It was a whole cultural shock for some."

Notes Theodore V. "Ted" Wells Jr. '72, who was recruited by Fr. Brooks and later became the BSU's second president: "When we arrived on campus, I dare say that Holy Cross was not ready for us and we were not ready for Holy Cross."

The environment was familiar to Martin, as he graduated from a predominantly white high school as student council president of a 2,500-person student body — one as large as Holy Cross. "I was used to that demographic; it didn't bother me," he says, "but I knew a lot of people that came on board that year didn't have that. And I think Fr. Brooks realized they didn't come out of that environment. So he and [then College President] Fr. Swords made an effort as if to say, 'What do we need to do to make this whole thing possible?'"

The answer was the formation of the Black Student Union, which received recognition as an official student organization, a budget and office space on the fourth floor of Hogan Campus Center. It was the first cultural affinity group in the then-125-year-old College's history, a trailblazer that paved the way for students from other cultural backgrounds to form their own groups and find their own voice in the years to come.

"What the Black Student Union was doing was giving the students on campus the opportunity to interact with each other, to have some commonality, to have some comfort level," Martin says. "We were there at the same time, we breathed the same air, we suffered the same way. I mean that not in a negative way, but that experience really made us brothers — literally, brothers. We went through some stuff on campus and it made us stronger."

A Time to Take Action

The organization would need to draw on that strength just a year later, when at least 60 black students — nearly the entire BSU — famously turned in their student IDs on Friday, Dec. 12, 1969, and quit Holy Cross in protest of the suspension of four black classmates. Martin names "the walkout" as the BSU experience of which he is most proud.

Earlier that week, 16 students (four black, 12 white) were charged with violating College policy and suspended after being identified in an on-campus protest of General Electric. The BSU had voted to remain neutral in the protest itself, but became involved after the suspensions, noting that a disproportionately high number of black students were charged because they were more easily identifiable, which the group argued was an act of racism. Of the 49 white students involved in the protest, only 12 were identified and suspended, compared to the five black students, four of whom were identified and punished.

"It wasn't so much about [the suspensions], it was more about, OK, why them?" Martin says. "'Well, we could identify them.' Well, I guess you could identify them! There's the old saying, 'it's the fly in the buttermilk!'" He chuckles, then continues: "I can look back and smile and laugh, but at the time this was going on, it was not quite that funny."

Martin and Wells decamped to nearby Clark University ("Our refuge," Martin recalls), where Fr. Brooks visited them, gave them cash out of his own pocket to ensure they ate and urged them not to leave the city altogether. The College administration, torn between upholding its policy and fairly treating its students, met continuously over the weekend, and the college careers of the BSU members — nearly all the nonwhite students at Holy Cross — hung in the balance. All of the students had a lot to lose, but few more than Martin, who was halfway through his senior year. He was already accepted into law school, and now he had quit one semester shy of receiving his degree.