Brianna Dominguez-Barnes ’23, a child of Deaf adults, had no idea of the intersection of health care and Deaf people until she was told the story of her birth.

“It’s a scary situation when someone is coming into your personal space and doing things medically,” said Dominguez-Barnes, noting that her mother shared how an interpreter was not available when she was in labor. “Patients want to be aware of what is going on with their own body. Not being able to communicate heightened her anxiety. Giving Deaf people equitable access to what’s happening to their own lives is essential.”

A current position paper from the National Association of the Deaf notes the “health care system has largely failed to both ensure and provide accessible language services and health information for many deaf individuals.” This, despite federal law requiring that means of effective communication is made available.

“There isn’t a lot of Deaf awareness in the hearing community. This leads to Deaf patients being ostracized,” said Trinity Offutt Decker '23, who works in human services with Deaf and hard of hearing individuals in Providence.

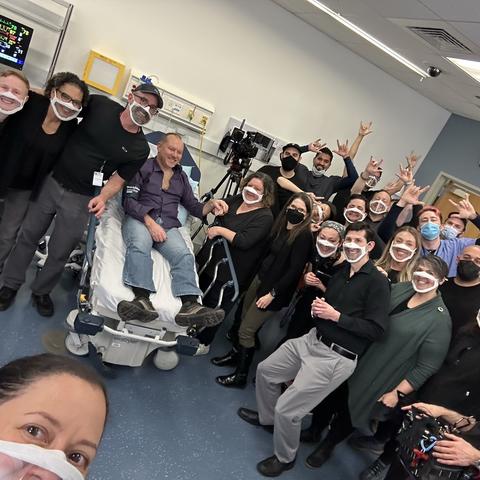

Dominguez-Barnes and Offutt Decker, now alumnae, and several current Holy Cross students sought to address this and in 2022 worked with Stephanie Clark, lecturer and program director of Deaf Studies and Sign Languages, on a film that teaches hearing health care professionals and students how to effectively communicate with Deaf, DeafBlind and hard of hearing patients. The students participated in the project through their intermediate American Sign Language course and the Donelan Office of Community-Based Learning, Teaching and Engaged Scholarship.