“Is there a certain time of the month when it’s better to give tests?”

Even with the positive press, the support of the president and the majority of its campus community, going coed was complicated and uncomfortable for some in those early years. Novelist Marilyn French, hired as an assistant professor of English in 1972, wrote the novel “The Women’s Room” during her four years at Holy Cross. The novel, which sold millions, is considered a pioneering work in feminist literature. “The Women’s Room” excoriates the all-male college where the female protagonist works. In a 1977 New York Times article, French, who left Holy Cross in 1976 when denied tenure, had harsh criticism for the College and recounted an anecdote that indicates just how foreign women were to some male faculty: “I don’t know whom to ask,” French recalled a Jesuit saying to her. “There are girls in my class. I never had girls in my class. Is there a certain time of month when it’s better to give tests?”

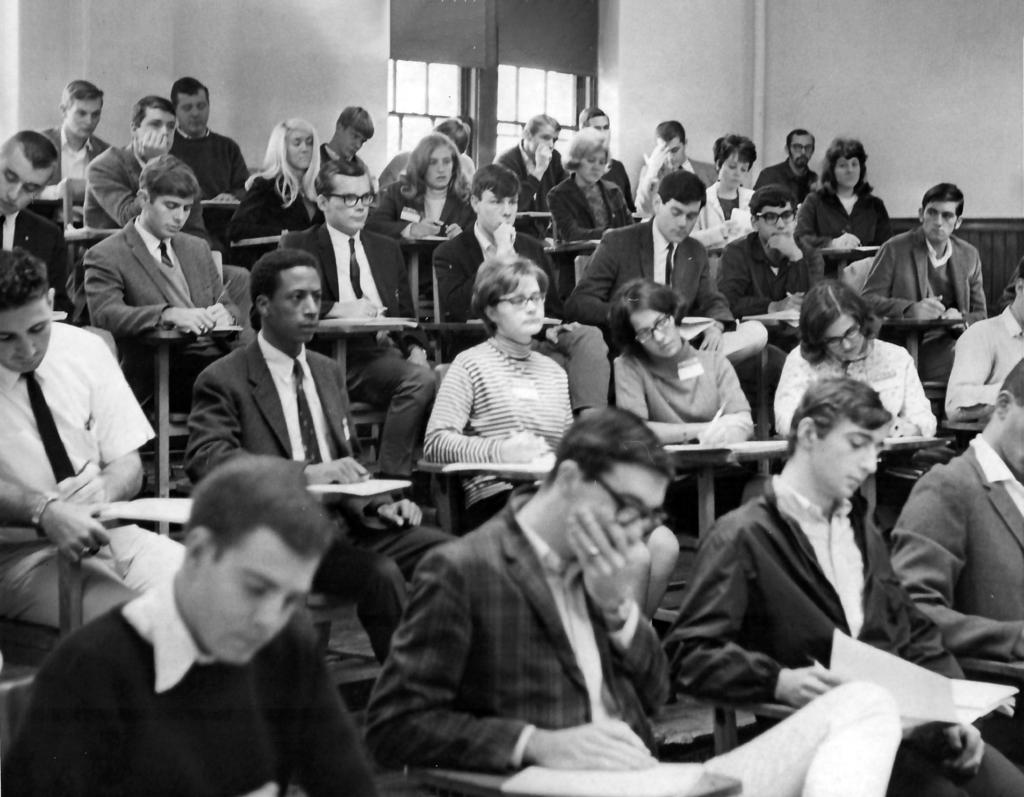

“I think some of the older priests had a difficult time having women there,” Cheryl Chapman ’74 told Holy Cross Magazine in 1997. “Certainly that showed up in some classrooms. They ignored our hands. They didn’t want to call on us in class.”

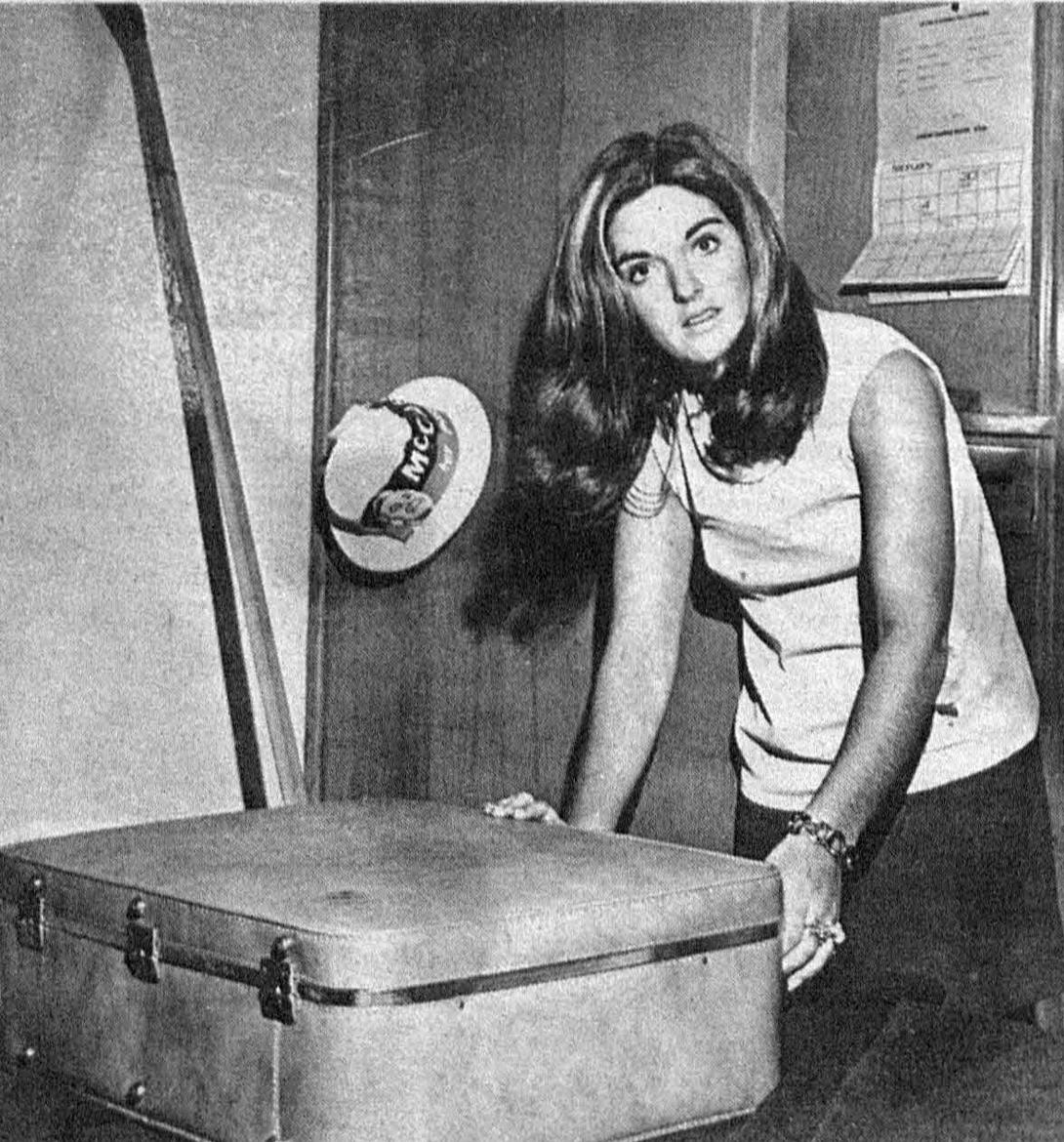

Other aggravations were the result of well-meaning missteps, Mary Jane Dinneen ’74 told Holy Cross Magazine in the same 1997 article. Some of those first female graduates characterized the College’s efforts to accommodate them as well intentioned, while occasionally clueless. The adding of yogurt, cottage cheese, skim milk and diet drinks to Kimball’s offerings went largely unnoticed. The administration’s worries about women needing bathtubs, lingerie sinks, washing, ironing and drying rooms along with kitchenettes were amusingly anachronistic.

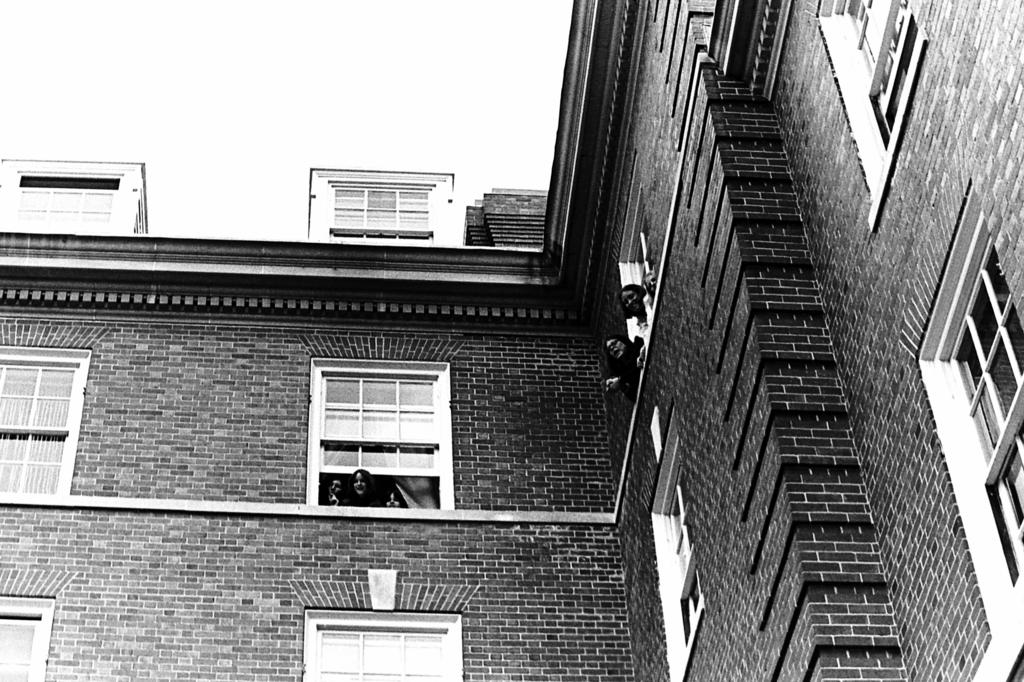

The College “had gone through a lot of effort to prepare for the women with the best of intentions and to the best of their knowledge. They did funny things like installing bathtubs because somebody had done some research and they found that if you had women on campus, you had to have bathtubs,” Dinneen said. “There was some general flakiness. We actually had locked doors on the dormitory floors and, at that time, I don’t think any other dorm did.”

The administration had its own learning curve. Its misapprehensions about women’s domestic inclinations and overreaching in ensuring their safety invited students’ scorn if the 1976 Purple Patcher yearbook is a fair arbiter: “Guards were posted at Mulledy, almost like Arab eunuchs from A Thousand And One Nights. Rape lights penetrated every nook and cranny of the hilly campus. Mulledy became a bastion of security; the women often wondered if they were well-protected treasures or well-guarded prisoners.”

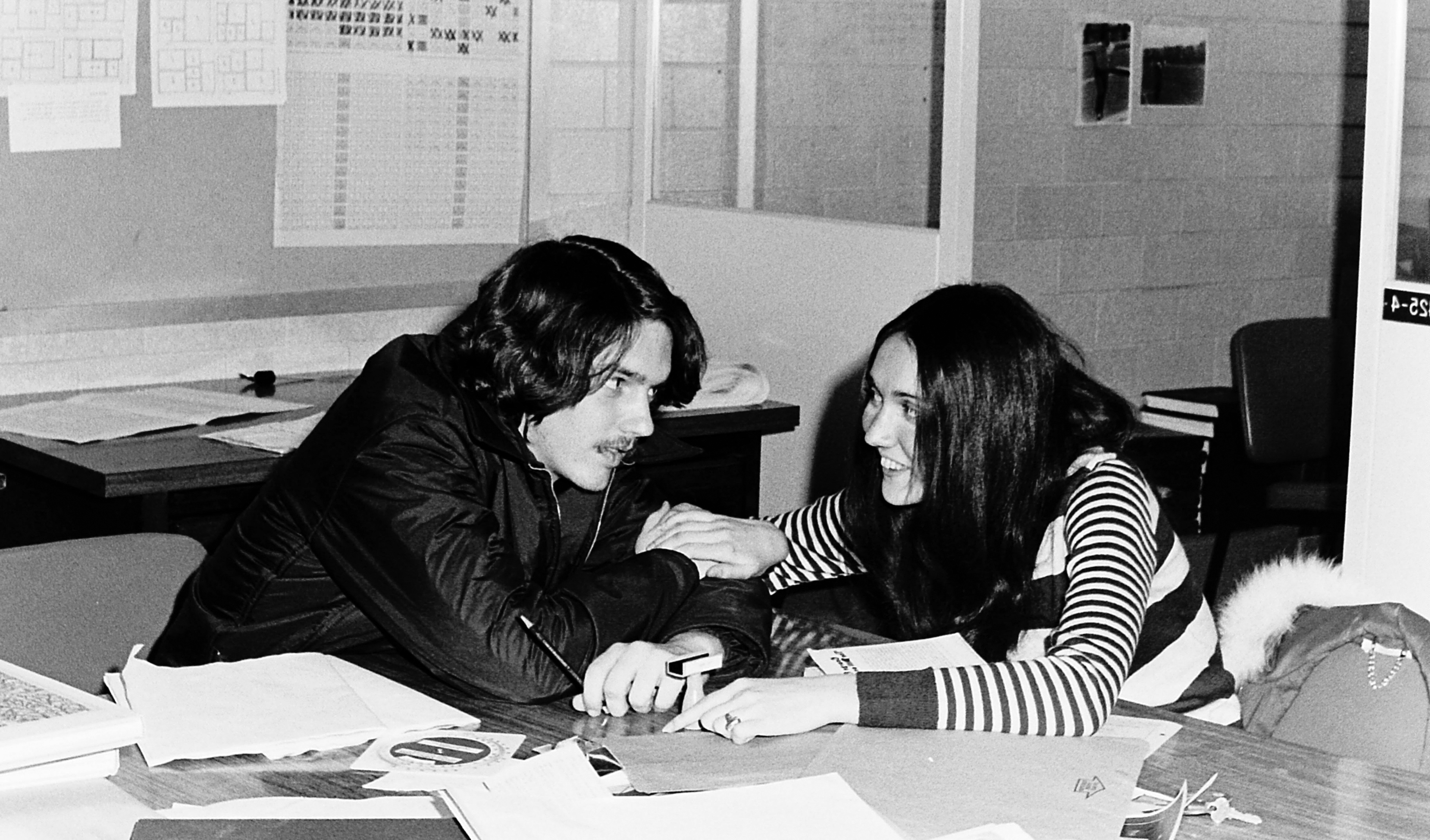

“It took a while of women being there for them to realize that women wanted a lot of the same things as the guys,” Dinneen said in 1997. “They wanted to play sports and to participate in all of the different campus activities.”

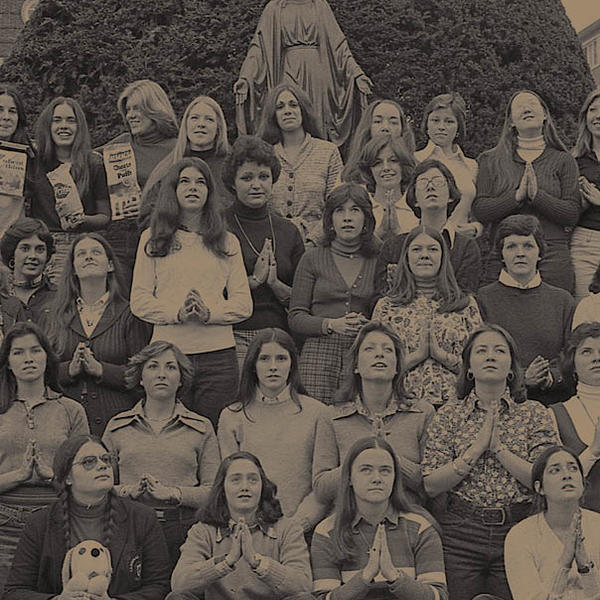

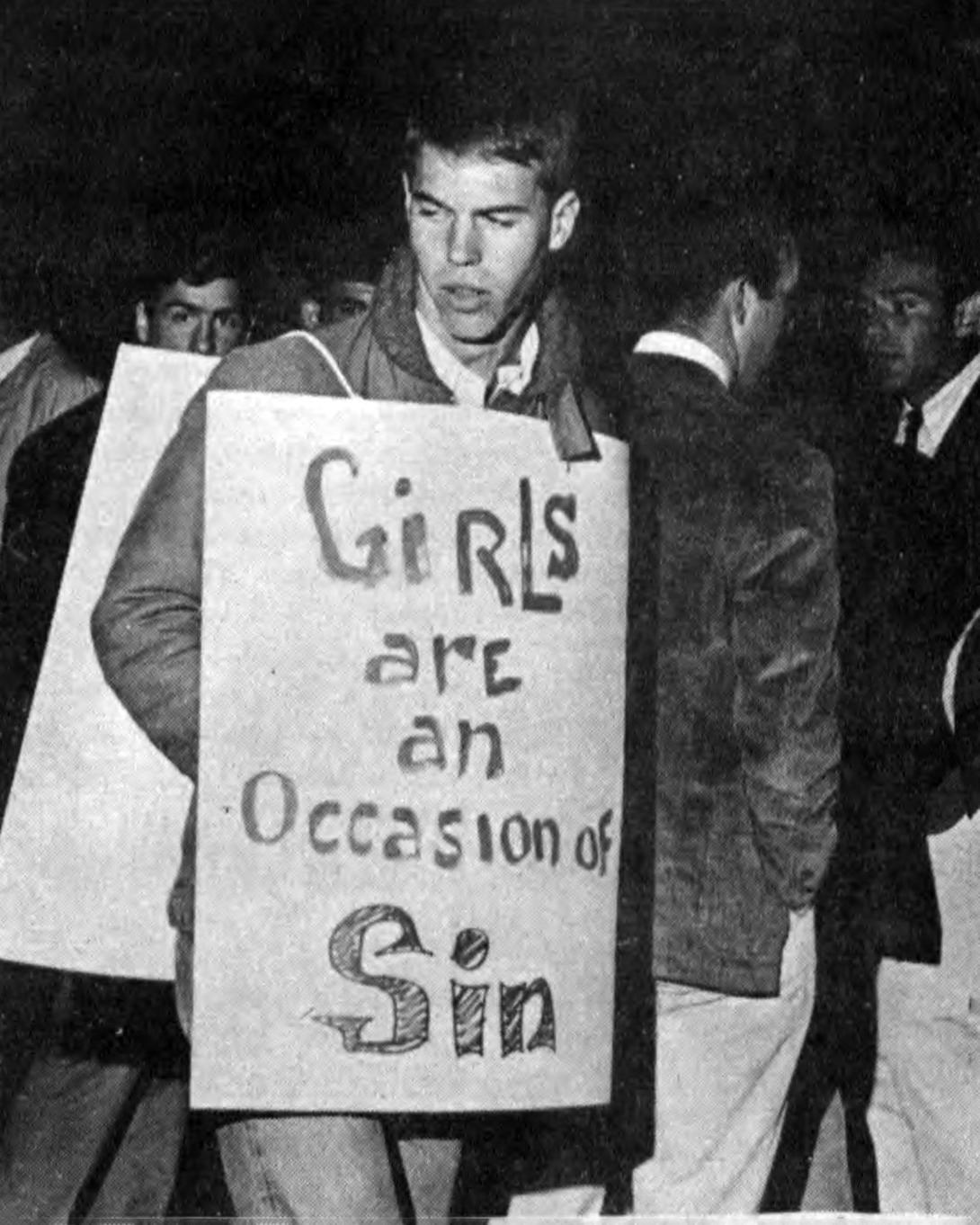

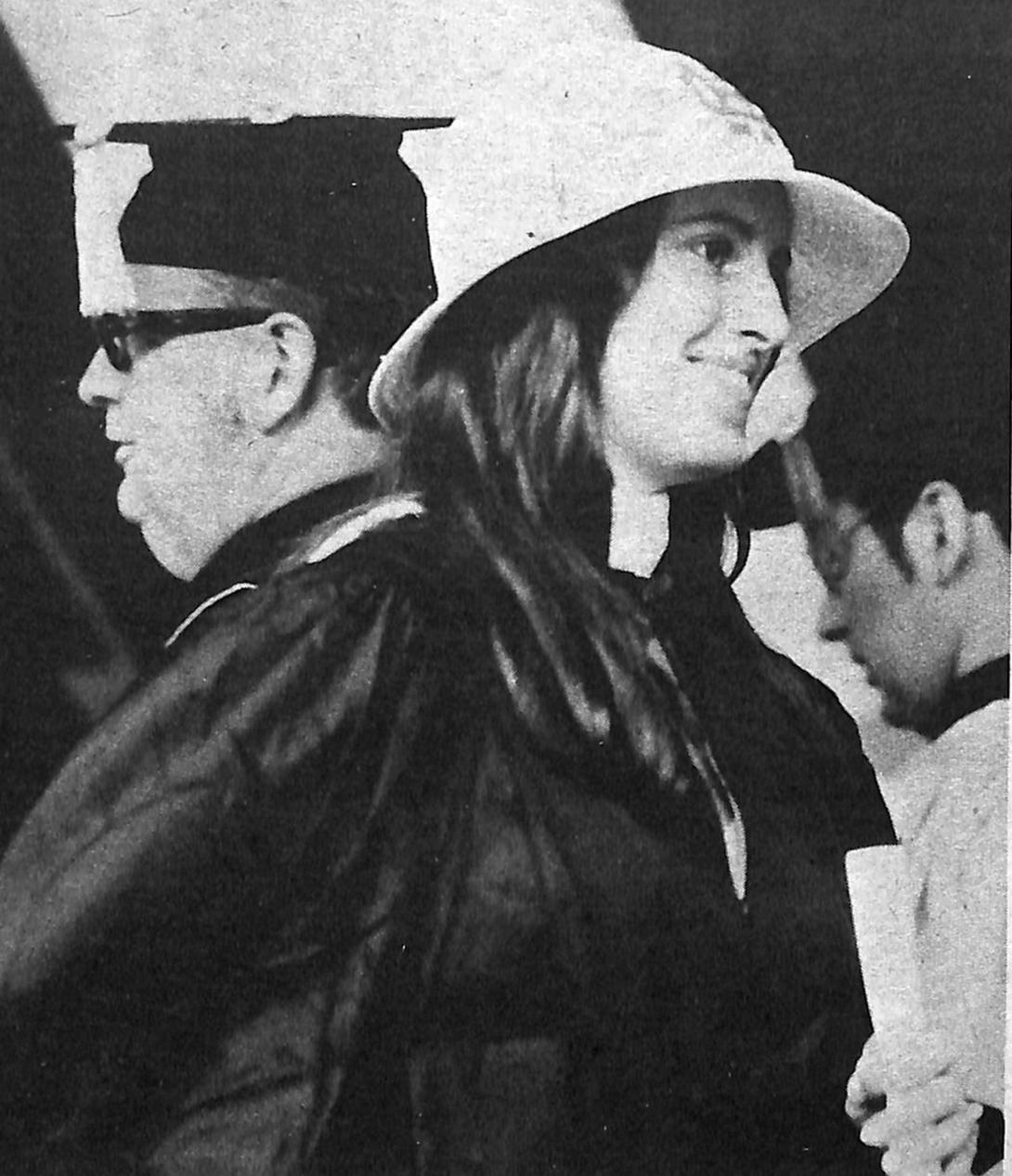

George Shea ’69 was one of a team of three admissions officers, led by James Halpin, to select the women who would become the first female Crusaders. The first early decision acceptance letters were sent in December 1971. Among the 30 women to receive offers, eight were daughters of alumni, and four of those ranked first in their respective classes. An additional 250 women were accepted into the class of 1976. “Classes up until that time were composed of a significant number of students from all-male, Catholic high schools, specifically Jesuit Catholic high schools,” Shea says. “So those young men hadn’t had a coeducational experience from high school on. So it may have been different for them. Most of the women, the experience they had was coed. ”

Alumnae remember professors fumbling in their addressing of female students. Some professors called the men in the class “Mr.” while calling the women by their first names. Others did the opposite. Less benign was one graduate’s account of a male professor telling her not everyone was cut out to be a math major when she went to him for help. Sexist behavior occurred outside of the classroom as well. A few alumnae recounted being catcalled by male students who scored their appearance on a scale of 1 to 10 as they walked to Kimball.

“It was intimidating to be a real minority,” said Suzanne Geaney ’76 in “Women on the Hill: Alumnae Reflect on Twenty Years at Holy Cross, 1972-1992” by Ann J. Cahill ’91. “It was harder to raise your hand if you were the only woman in the class. Sometimes well-meaning faculty members would say, ‘Well, let’s hear from a woman about this.’ So even if you weren’t ready to talk, you had to. So that was my motivation. I was never unprepared.”