For years, Sophie Sundaram ’26 has tried to answer two questions: What does it mean to really know another person? What does it mean to truly know yourself?

To accomplish this, the studio art major has been engaging in what she calls “emotional detective work” – from trying to guess the tone of her mother’s reading material based on her facial expressions and reading stream of consciousness stories from Virginia Woolf and James Joyce to falling in love with international arthouse cinema and the work of filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman and Krzysztof Kieślowski. The ultimate goal: to understand emotions — the way they shift and change and how they can be used to solve the mystery of who a person truly is beneath the surface.

With the onset of the pandemic and the rise of videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom, more interactions than ever are taking place on screens, which offer close-up images not only of the person on the other end of the connection, but also of oneself. It’s a more intimate interaction than humans are used to, Sundaram explained, but because of the screen, it’s also more distanced and curated, constrained by the borders of the camera.

“I became really interested in how the screen shapes emotional visibility and that kind of tension in the clarity and distortion – meaning, what we're seeing and what we think we are seeing when we're communicating with others,” Sundaram said.

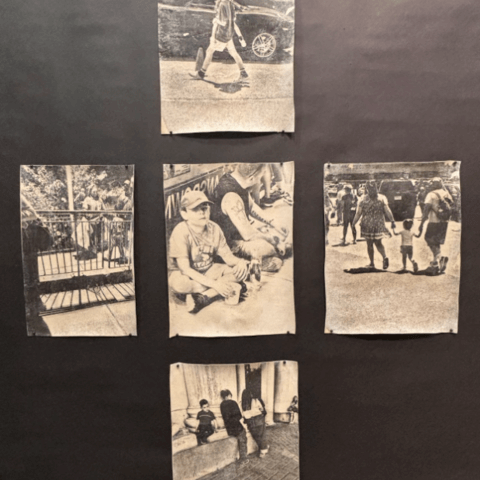

This interest became the foundation of Sundaram’s first solo body of work. Through the College’s Weiss Summer Research Program, she spent summer 2025 zooming into the emotions of herself and others through a camera lens, and trying to understand their complexity off the screen via art.

Looking inward

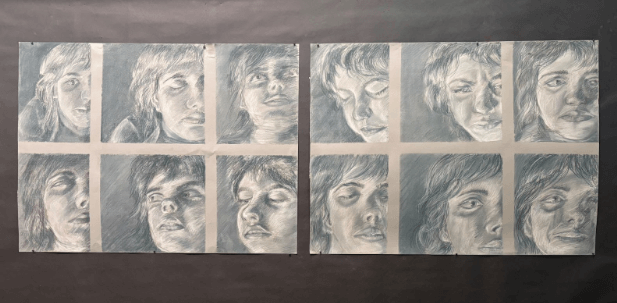

Like many who live far away from loved ones, Sundaram makes a lot of video calls, talking to her parents in Concord, Massachusetts, her sister in Belgium and her extended family in Poland. But over summer 2025, instead of simply talking to them, she also used the calls to document her emotions. While FaceTiming daily with her sister and parents (who were abroad for most of the summer), Sundaram would take screenshots or videos of the call, then use the images to later draw a self-portrait. Sometimes the self-portraits were neutral expressions of everyday conversation, while others displayed more distinct feelings, like happiness or sadness. Drawing a portrait of herself crying after receiving a piece of bad news, for example, was emotionally charged for Sundaram and for her viewers at her end-of-summer critique.

“I think one of the reasons that people resonated with that one is, how often do we actually slow down enough and sit with the discomfort of somebody who is crying, who's in distress, who's sad?” she said. “Sadness is still quite taboo in some ways. Even though you can find a hundred people on Instagram who are crying, there is something about that that is very packaged, you can flick through it and it feels very commercial. When you draw something, you have to sit with it. There was some uncomfortableness with actually looking at myself crying, and having to sit with that and draw it.”

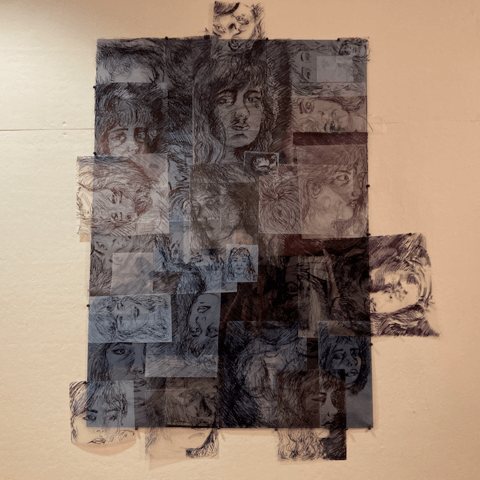

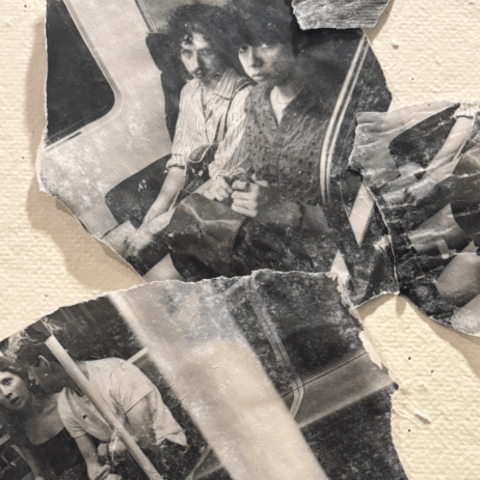

Using a variety of materials, including charcoal, ink, oil bar and acrylic pours, on varied surfaces, such as vellum, plexiglass, paper and canvas, Sundaram was able to experiment with breaking down the idea of curated images that are common on social media and capturing the emotional intensity and ambiguity she was experiencing. Sometimes that meant breaking free from the rectangle shape of screens. Other times, it meant tearing up a piece she was dissatisfied with at the prompting of her advisor, Assistant Professor Leslie Schomp, and creating something new.

“A certain kind of emotional moment, expression, light, [or] gesture would grab me, and then I'd break it down, trace it, draw it, layer it, cut it apart,” Sundaram said. “And from those fragments something new and emotionally resonant would kind of emerge.”

“She learned a lot about materials through trial and error. There are some things you can teach about materials and sometimes you just have to try it,” Schomp said. “I'm really excited when she'll take a prompt and interpret it. It's a fine line between being lost and doing what somebody tells you, and having an intrinsic sense of what you need to do for yourself, because you are the artist and you're the author of this work. Often she interpreted my responses and used the ones that felt most connected to her.”

The act of creating art itself also invited Sundaram to slow down long enough to pay attention. Whether it was drawing, doing photo transfers or slowing a video clip enough to see how her emotions changed, she was able to notice more than if she was just taking a photo or video alone.

“I think in a really rushed and curated world, attention becomes really radical. I mean, I think about how hard it is for a lot of young people to pay attention to even a whole movie these days,” she says. “So drawing and making art in general, even when it's from photographs, is really important, because it makes space for that emotional slowness, for trying to understand that ambiguity in a different way.