It's subterranean champagne soirees and secret speakeasies. High adventure propelled by hurricanes and blizzards. It's fraternity forged in the clandestine heist of a decommissioned missile. It's street cred earned in hall jai alai and inspired scribbling done in drafty garrets.

It's a story nested in stories so numerous they'd tax Scheherazade in the telling. At the center of it all is a house with space for infinite memory, by a beach with no sand nor ocean.

Over its 177 years, the College has offered a variety of residences for students, yet none seems to have an everlasting pull on its former residents like Wheeler Hall.

Rev. Anthony J. Kuzniewski, S.J.'s 516-page history of the College, "Thy Honored Name: A History of The College of the Holy Cross 1843-1994," states that Wheeler was built to alleviate overcrowding in Fenwick and O'Kane. The dorm opened in January 1940 and was named (quite ironically, it would come to pass) for the late Rev. John D. Wheeler, S.J., prefect of discipline. Initially, seniors occupied the first four floors and juniors, the fifth. Total cost: $415,000.

College Archives and Special Collections is home to blueprints, newspaper clippings and pictures of Fr. Wheeler, but save for a single newspaper clipping about the opening of his namesake's short-lived basement bar, culture and pride aren't so much the concern of historical record. So, on the occasion of her 80th birthday, the question is put to alumni: What is it about Wheeler?

"I really don't think anyone was there by accident," says Cyndi Tully Webber '89, a former RA. "Whether you had big hair and high heels, were a tough-as-nails straight shooter or from a sheltered, single-sex Catholic school upbringing, you found your home in Wheeler. We all bonded. Everyone I met along the way there belonged in Wheeler. Everybody."

Stephen Hickey '73, P01 arrived at Wheeler in the fall of 1969. Then, the newest dorm, Mulledy, was the place to live. Hickey preferred Wheeler. "People didn't tend to leave Wheeler because it was the most convenient dorm. The Field House and Hogan were half a hill up; the library was half a hill down. And Wheeler had a sense of community. Wheeler was the only totally integrated dorm on campus. We had students from all four classes in it. A lot of guys spent their whole college career at Wheeler."

It was in an enviable location for another reason. "The College would bus women from all-women's colleges to the Field House or the Hogan parking lot and what was the first dorm you'd see? Wheeler," he says.

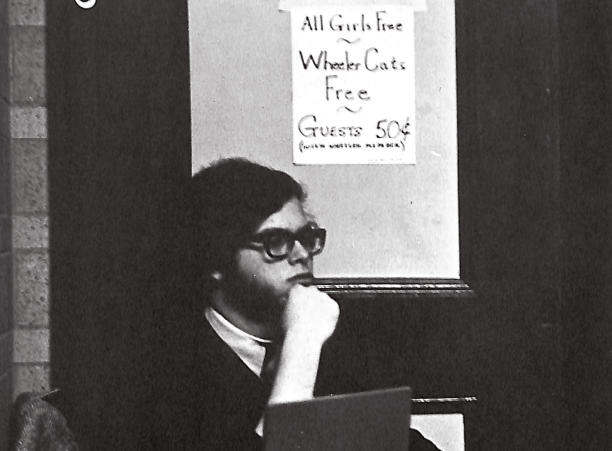

At the ready was the lounge, The Brickskellar. A black-and-white photo from the 1973 edition of the Purple Patcher shows a motley arrangement of folding chairs and mismatched tables, ashtrays, playing cards and empties. "A certain amount of interior renovation made Wheeler a more comfortable dwelling for the hundreds of Stephen Daedalus's [sic] that descend yearly to the house," the Patcher reported. "This title is appropriate because the undergraduates' years spent within the confines of the house are still those years of hopeful searching, to come to a full realization of what life at Holy Cross entails. From the penthouse level of Wheeler, one may oversee the seven hills of Worcester, but hopefully no one will attempt to make his flight from this height before coming to terms with his values and goals." (Clearly the writer was in Professor Edward Callahan's Joyce seminar.)

Hickey was one of 10 students with keys to The Brickskellar. "We served beer and booze. Wine? Ha, no," he says. "It was 25 cents for a 12-ounce beer and 50 cents for a hard drink. You had to buy tickets, $1 or $5 tickets. A dollar got you five beers. It was always packed. We opened when we opened, and we closed when we closed. Every Friday in the fall each academic department was invited over, providing a relaxed atmosphere for the students to get to know the faculty and have a drink with students. Although the room was open most Friday and Saturday nights, the rest of the week was open by request for Bruins or Celtics games or other special events."

And this was a business with a social mission decades before there was such a thing, Hickey notes. Proceeds of the Wheeler social room were often donated to student organizations.

At the time of the lounge's opening, the administration praised the enterprise. In a letter to the dorm's residents, Dean of Men McClain wrote, "The other houses now have a new standard for which to strive, both in fellowship and style ... from now on when I think of community, I will think of Wheeler House."

O'Neil, director of the RA program, was even more effusive in his praise: "I think the men of Wheeler House did a fine job in offering the campus something with a little class," he wrote to the residents. "I hope that you are successful in making Wheeler House the best place on campus to live."

"Sophomore year, Lehy, Hanselman, Clark and Mulledy houses were the preferred resident selections," says Paul Howard '71. "Wheeler 507, a.k.a. The Penthouse, was our home. Our roommate, Ed, built a bar and we painted our ceiling in lime, pink and yellow. We viewed Wheeler House as the epicenter of our Holy Cross campus and Wheeler 507 cemented our lifelong friendship and treasured memories of our Holy Cross experiences."

It Has a Certain Energy

Feng shui dictates that a building be designed to encourage optimal flow of energy, qi. It's unlikely Boston architectural firm Maginnis and Walsh had this in mind in Wheeler's design (they also designed St. Joseph Memorial Chapel, Dinand Library and Alumni Hall), yet alums like Dave Curran '73 say the dorm's layout created a neighborhood atmosphere. Students took to the halls like city dwellers to stoops. "You walked out your door," Curran says, "and you were immediately part of things. No one ever wanted to leave Wheeler. We had the luck of having a good mix of people."

The hallway was a living room, notes Mary Lynch Supple '82, P17, P13. People would gather and chat over popcorn or even pop champagne, on occasion. "We held a reception on Wheeler 5 when Luke and Laura got married on 'General Hospital,'" Supple recalls. "It was a real community with a special bond. We would gather to walk to Kimball together and gather to walk to 10 o'clock Mass Sunday nights — and go to the pub on our way home."

"There was something about the way the light came in through the dorm room windows, casting a cozy glow in the afternoons and the old-fashioned radiators that smelled so good when the steam heat came on," remembers Lesley Stackler '88. "These contributed to an atmosphere of comfort and happiness that invited friends to visit and hang out in each other's rooms for hours on end. I met my best Holy Cross friends in Wheeler and our friendship has endured to this day."

This caused concern for some parents, especially dads leaving their 18-year-old daughters at college for the first time, recalls Diane McDonnell Pickles '89. "My dad took one look around and said, 'Get back in the car. You're not staying.'"

The pair reached a compromise. "I'll let you stay, but you have to promise not to date anyone on this floor," Pickles' father told her. "And no football players."

This year, Pickles celebrates her 30th wedding anniversary with hallmate and former Holy Cross football player, Bill Pickles 88.

A metal fire door divided women from men on Wheeler 2. It was mostly left open except during hall jai alai matches, says Jonathan "JW" Cahill '88, P23. The door had to be closed to play the game, and it kept the women from serious injury.

"Well, it involved throwing a golf ball against that door, and it would come flying back and it was dangerous and that's what was great," Cahill says. "It wasn't advisable for anyone to play, but it happened quite often that guys from other dorms came to play."

Another Wheeler draw: TRM, Cahill's band, which won the College's Battle of the Bands four years in a row. "The gigs in Wheeler basement were some of the best gigs I've done. We'd walk downstairs to the Wheeler social room and people would be lining the hall and cheering," Cahill recalls.