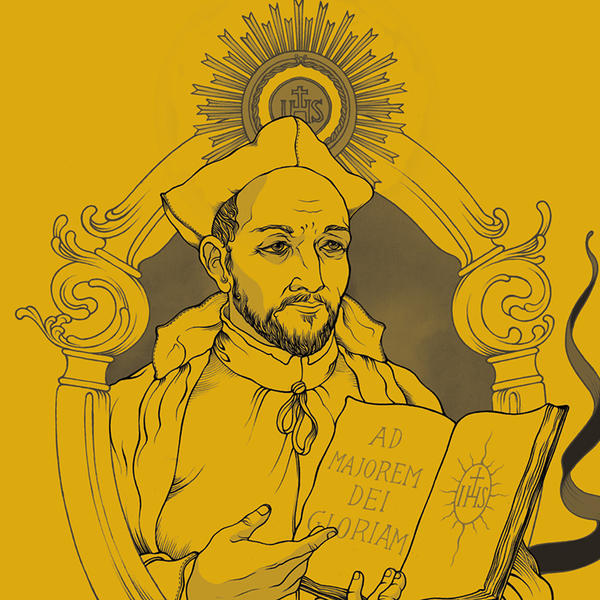

Ignatius asks, "Who am I called to be?"

Born in 1491 at the castle of Loyola in northern Spain, Ignatius was the youngest of 13. "He wanted to be successful in the world as he understood it, which for him meant excellence at arms when needed, but also marrying well and increasing the fortunes of his family," Fr. O'Brien says. While defending Pamplona from French troops, Ignatius was hit by a cannonball, shattering his right leg. Initially, he was so aesthetically concerned with how his leg was healing that he asked to have it re-broken and set again, even though anesthetics were not available.

"While recuperating at the castle of Loyola, he found none of the tales of chivalry that he loved to read," writes historian Rev. John W. O'Malley, S.J., Hon. '99, author of "The First Jesuits."

Instead, only two books were available: the illustrated "Life of Christ" by Ludolph of Saxony and a book on the lives of the saints. Laid up in bed, Ignatius had months to consider his next move. He began to notice that daydreams of returning to his old life left him feeling "dry and agitated in spirit," Fr. O'Malley writes.

In contrast, the idea of modeling his life after the saints he read about brought "serenity and comfort." This process of discernment helped him choose a new path. As soon as he was able, he set out on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

"I talk to students about Ignatius because his story is relevant to us today," says Michele Murray, senior vice president for student development and mission and dean of students. "Ignatius' story is a roadmap for dealing with major heartache and disappointment. I find that this is part of being human: allowing your heart to break and seeing very real desires — good desires — all crumble in front of your eyes. I don't know a person who has not had that experience.

"Ignatius offers us a lot of hope that there's life beyond the disappointment — and that life is bigger and more rewarding and more engaging than what we can imagine on the near side," she notes." It takes courage and openness to possibility to recognize that disappointment is not the end of the road, often it’s the beginning. Ignatius and the early Jesuits teach us that."

In the pandemic times of today, many people around the world are searching for any meaning they can take away from the pain of isolation."Ignatius let the time and stillness and solitude that was forced upon him become a means of reflection," Fr. O'Brien says. "And that, I think, is relevant to all of us."

On disappointments and setbacks Ignatius' injury at Pamplona would not be the only hurdle he’d face. His new path — even his journey to the Holy Land — brought new disappointments. "At every turn for a while he hit up against roadblocks and had to ask himself, 'Well, now what do I do?'" Fr. O’Brien says.

Due in part to an outbreak of the plague, a short stay in Manresa, Spain, turned into months. Ignatius spent hours praying in a cave and reportedly suffered from mental anguish and doubts of faith. "[He] gave himself up to a regimen of prayer, fasting, self-flagellation, and other austerities that were extreme even for the 16th century," Fr. O'Malley writes.

Coping with these struggles, he began to write as a means to help himself and others. These writings would become part of the Spiritual Exercises — a practical handbook of prayer, meditation and contemplative practice, a hallmark of the Jesuits used to guide people seeking a deeper relationship with God. "Ignatius really found a way of distilling a lot of wisdom that had been passed on, even from early Christianity," Fr. O'Brien says of the Exercises. "He put them together in a readily accessible format. That's the real innovation of Ignatius."

For years, Murray has carried with her an excerpt from the beginning of the Exercises: "The shorthand for it is to listen generously, to give the speaker the benefit of the doubt. At this point in the history of the world, that simple concept feels so countercultural — the idea that we can listen not to argue, but to understand."

Ignatius finally made it to Jerusalem in 1523 — only to be asked to leave two weeks later by church officials who could not guarantee his safety there. Once again, he found himself facing a familiar question: Now what?

Stronger in community

Ignatius decided that getting an education might be the key to furthering his spiritual work. So, at age 33, he returned to grammar school. After years of study, he moved to France to attend the University of Paris. There, he roomed with fellow students (and future fellow saints) Peter Faber and Francis Xavier. Together, the trio would eventually found a new religious order called the Society of Jesus.

"Outside my office window is the statue group of the three founders," Murray says. "And I like to tell students not just about Ignatius, but about all three of them — that they were roommates at the University of Paris. They came from different life experiences and didn't necessarily get along at first, but look at what they did. Their work together and the schools they founded changed the world. Their sense of brotherly love laid the foundation for us at Holy Cross and for all of the Jesuit works. When we talk about community, it's not an abstract term. It comes directly from the experiences of the early Jesuits."

The Ignatian Colleagues Program (ICP) is one way Jesuit institutions across the country are connecting as a broader network, strengthening and fostering the Ignatian tradition in their campus communities. Offered through the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities for more than a decade, the 18-month program for faculty and administrators includes workshops, retreats, international immersion trips and capstone projects.

This year, Fr. O'Brien is helping lead a new initiative at Holy Cross called the Campus Colleagues Program, a sort of local version of ICP. The idea originated as a capstone project created by Holy Cross community members and ICP alumni Paul Irish, associate dean of students, and Robert Bellin, professor of biology. Led also by Emily Rauer Davis '99, associate chaplain and director of domestic immersions, the program focuses on Ignatius’ tradition of self reflection.

"It's bringing together faculty and staff, in relatively equal numbers, to engage with their own sense of call and mission on this campus," Fr. O'Brien says.