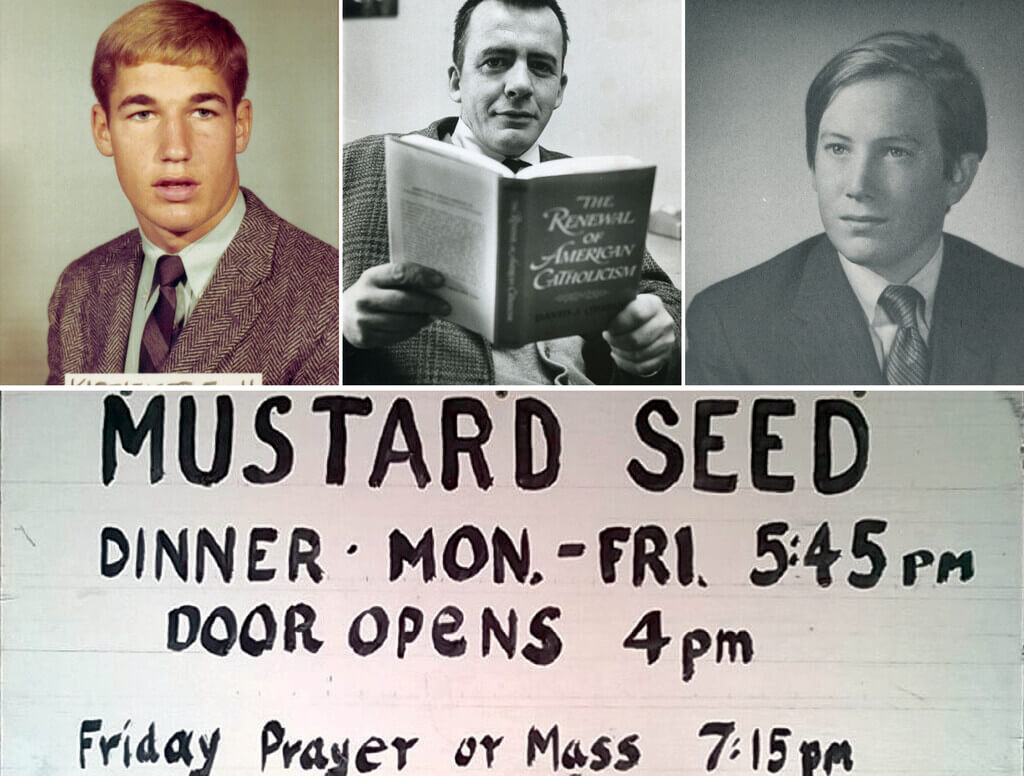

Credit the Dominicans, the Jesuits, Brown University, chance, fate, football or an intrepid Providence cabbie — all played their part in how high school senior Frank Kartheiser ’72, Hon. ’19 ended up on the steps of the Hogan Campus Center without any idea of what to do next.

It was 1968, and Kartheiser, a high school football player, had traveled east from Chicago at the invitation of the Brown University football team, when, on a whim, the Dominican-educated Kartheiser hailed a cab and asked the driver to take him to “Warchester” — specifically, the College of the Holy Cross. The cabbie dropped him at the top of College Hill. With no appointment and no one to meet, Kartheiser sat on the steps of Hogan and thought, What am I doing here? I’m a thousand miles away from everybody I love and care about. What am I doing?

Fifty-seven years later, Kartheiser smiles.

“It worked out OK.”

Kartheiser has spent more than 50 years in Worcester, working for the betterment of his neighbors in a variety of ways and roles. He began with the Mustard Seed, a soup kitchen and food pantry he co-founded in 1972 with his wife, the late Mary Brenda Norton Kartheiser, and the late Shawn Donovan ’70. The Mustard Seed has been a Worcester staple ever since and launched Kartheiser’s career as a social justice advocate, community organizer and founder of subsequent organizations, including Worcester Interfaith, a multiracial community organization.

Kartheiser’s freshman year, 1968, was particularly tumultuous in the United States. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated within months of one another, King one week before the Civil Rights Act became law. On campus, students like Kartheiser joined peace and justice coalitions and staged protests over the country’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

His intention in coming to Holy Cross was to get a solid education, play some football and become a businessman, but world events and the death of a friend and high school classmate, a serviceman in the Vietnam War, moved Kartheiser to make a life-altering decision in 1971, his junior year.

“The stories about Vietnam and what was happening, why we were there — the difficulty even for the administration to explain what we were doing there — spurred me to identify professors who could help me think about it,” Kartheiser says. “People were dying, and stopping the war felt more and more urgent.”

He decided he would drop out of school to do anti-war work. If drafted, he intended to be a conscientious objector.

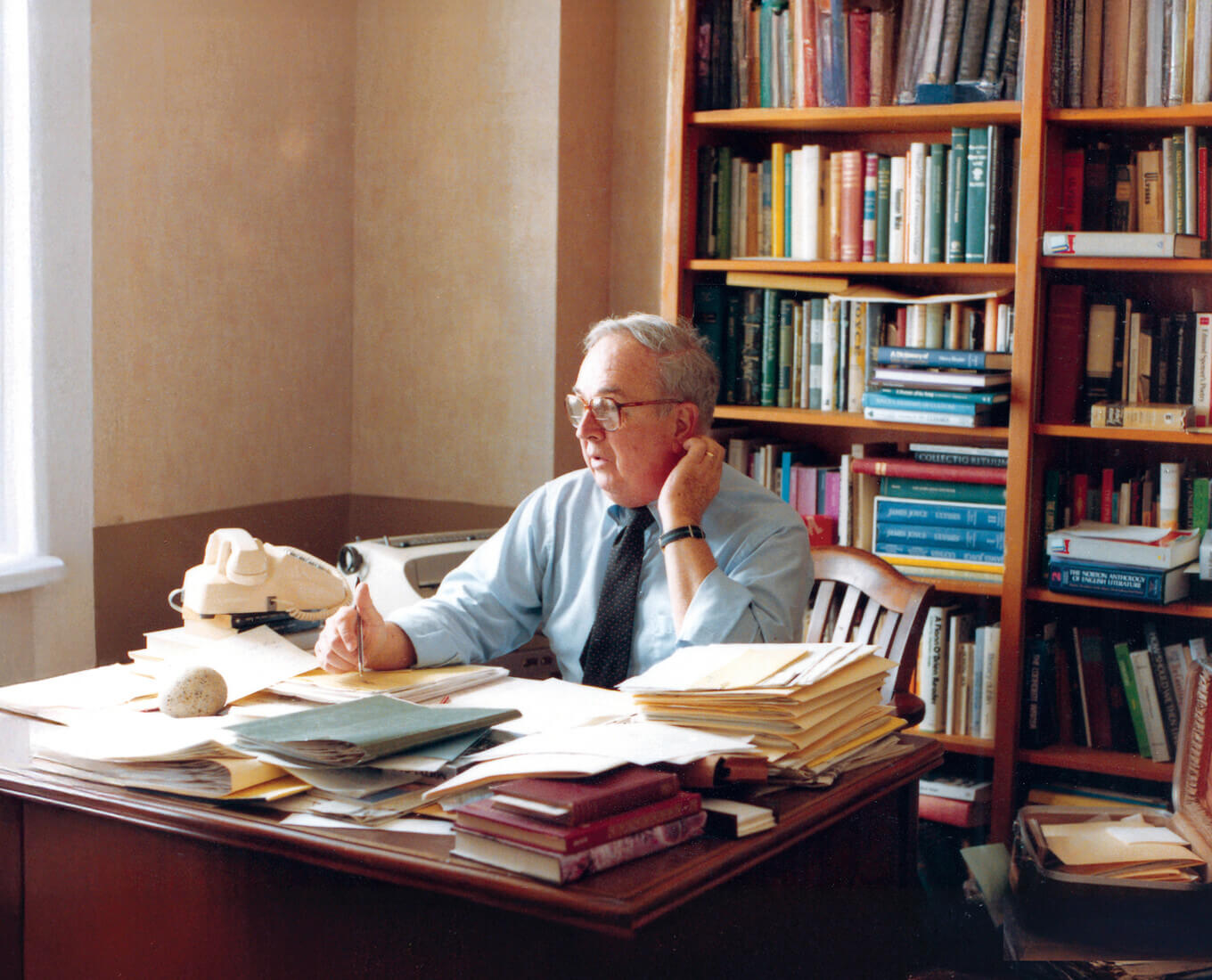

At a Catholic Peace Fellowship meeting, Kartheiser ran into Professor David J. O’Brien, Loyola Professor of Roman Catholic Studies, and told him of his decision. The two had been friends since meeting on a picket line two years earlier at an A&P warehouse, then at the bottom of College Hill. They were there supporting the United Farm Workers, the labor union formerly known as the National Farm Workers Association, founded by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. With his parents’ permission, Kartheiser left Holy Cross and lived with the O’Brien family for a year while working at Worcester State Hospital, counseling people with heroin addictions.

O’Brien introduced Kartheiser to the Catholic Worker Movement, and the more the younger man learned about social justice and activism, the more his thoughts turned to performing works of mercy as an expression of protest. Kartheiser and Donovan decided to establish a community space in Worcester, settling on a storefront at the corner of Pleasant and West streets, 2.5 miles from Holy Cross.

It was a second “How-did-I-get-here?” moment for Kartheiser, and this one was on display for all the neighborhood to see.

“A FAITH-NECESSARY JOURNEY”

“We opened in October of 1972, and we were just sitting in this big, empty storefront. And we’d said to each other that we weren’t going to decide what to do; we were going to wait and see what the people think the need is,” Kartheiser recalls. He chuckles at the memory.

After a few days of wait-and-see, a woman walked into the building.

“What are you doing here?” she asked Kartheiser and Donovan.

“We said, ‘We don’t know. What do you think we should be doing?’” Kartheiser recalls.

“Well,” she said, “get some coffee. Come on, guys. Put a pot of coffee on.”

Donovan and Kartheiser bought a coffee pot; the neighborhood woman brought her friends. Then, there was a suggestion that they serve soup. Kartheiser and Donovan set soup to heat on a radiator as the space didn’t have a kitchen. There was no plan, no budget, no paid staff. Some people came with food, some to dine. And that was fine by the founders, who saw a shared meal as less an extension of charity than an opportunity to create community.

Eleven months into their first year, there was a trash bin fire, and the landlord wanted the Mustard Seed out of his building. Soon thereafter, a house on Piedmont Street was listed for sale, and a down payment arrived from an unexpected source: A man contacted the Mustard Seed organizers sharing that his daughters had raised $3,000 selling Mustard Seed key chains, purchased for 10¢ and sold for $2.

“Three grand was enough to put a down payment on the triple-decker at 93 Piedmont St.,” Kartheiser says.

The “Seed,” as Kartheiser and other volunteers call it, was back in business. The Kartheisers lived in the inner-city neighborhood, where they raised two daughters, Alexandra and Kendra. Over the years, Kartheiser founded or co-founded other organizations, such as the Piedmont Resident Organization, the Castle Street Housing Cooperative, the Worcester Inter-Religious Legislative Network, Worcester Interfaith and the Worcester Community-Labor Coalition. In 1987, he returned to Holy Cross, earning his bachelor’s degree in religious studies the following spring.