An unseasonably cold and steady June downpour meant nearly every guest at the Mustard Seed kitchen and food pantry ate their dinner of hot dogs, macaroni and fruit in some degree of discomfort.

Though the start of summer was less than a week away, diners — called guests at the Worcester nonprofit — were bundled in wet jackets and hats or sodden hoodies. Between serving meals, volunteer Paula Bushey fielded requests for blankets, backpacks, clothes, sneakers and sleeping bags from people preparing for another night outdoors.

For some, the street feels safer than the shelter, Bushey explained, as she handed Felicia (last name withheld) a pair of size 8 sneakers. Felicia nodded. But a night out in the rain means every item she is carrying will end up soaked, and she has no way of drying anything. Felicia confided that she’d been hospitalized 15 times for exposure-related pneumonia since becoming homeless last year.

Next, two elementary school-aged boys asked for socks. They are Afghan refugees and brothers who arrived with their parents and nine siblings in Worcester after the United States military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. Bushey gave each boy two pairs from an armoire, which also contained single-use bottles of shampoo, cakes of soap, underwear and other necessities. More guests gathered. Are there backpacks, blankets, coats, socks, and T-shirts? they asked.

All the while, meals were served, takeout bags prepared, and water and coffee distributed. What was clear on this stormy night: There is chronic need in the city, New England’s second-largest.

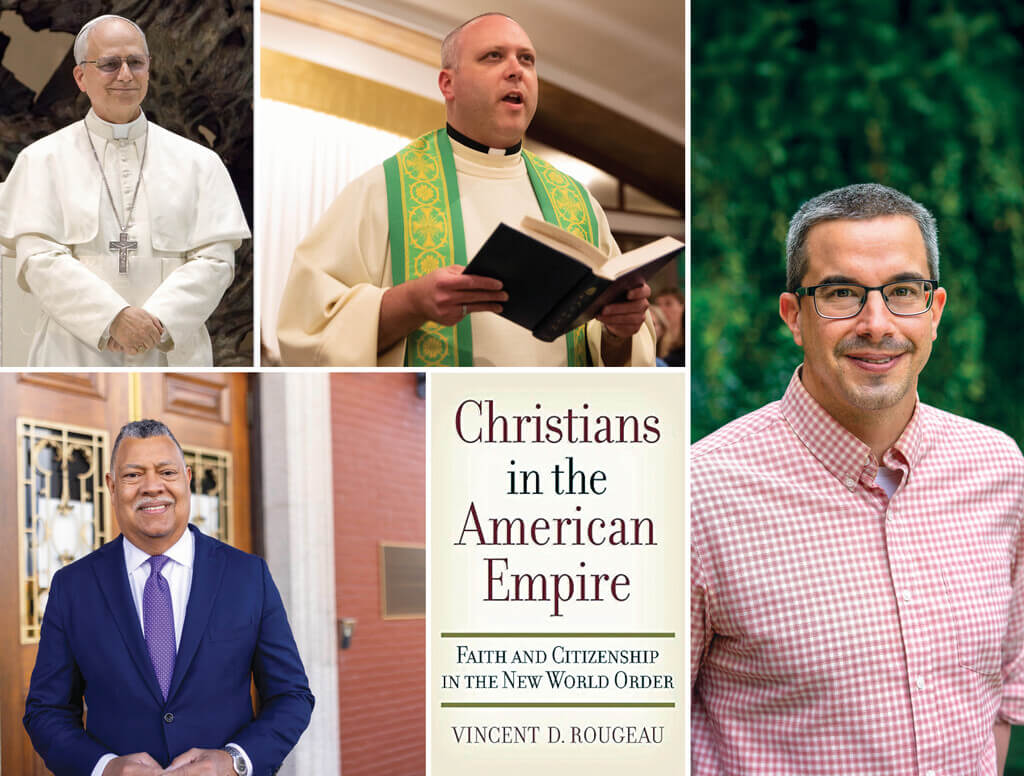

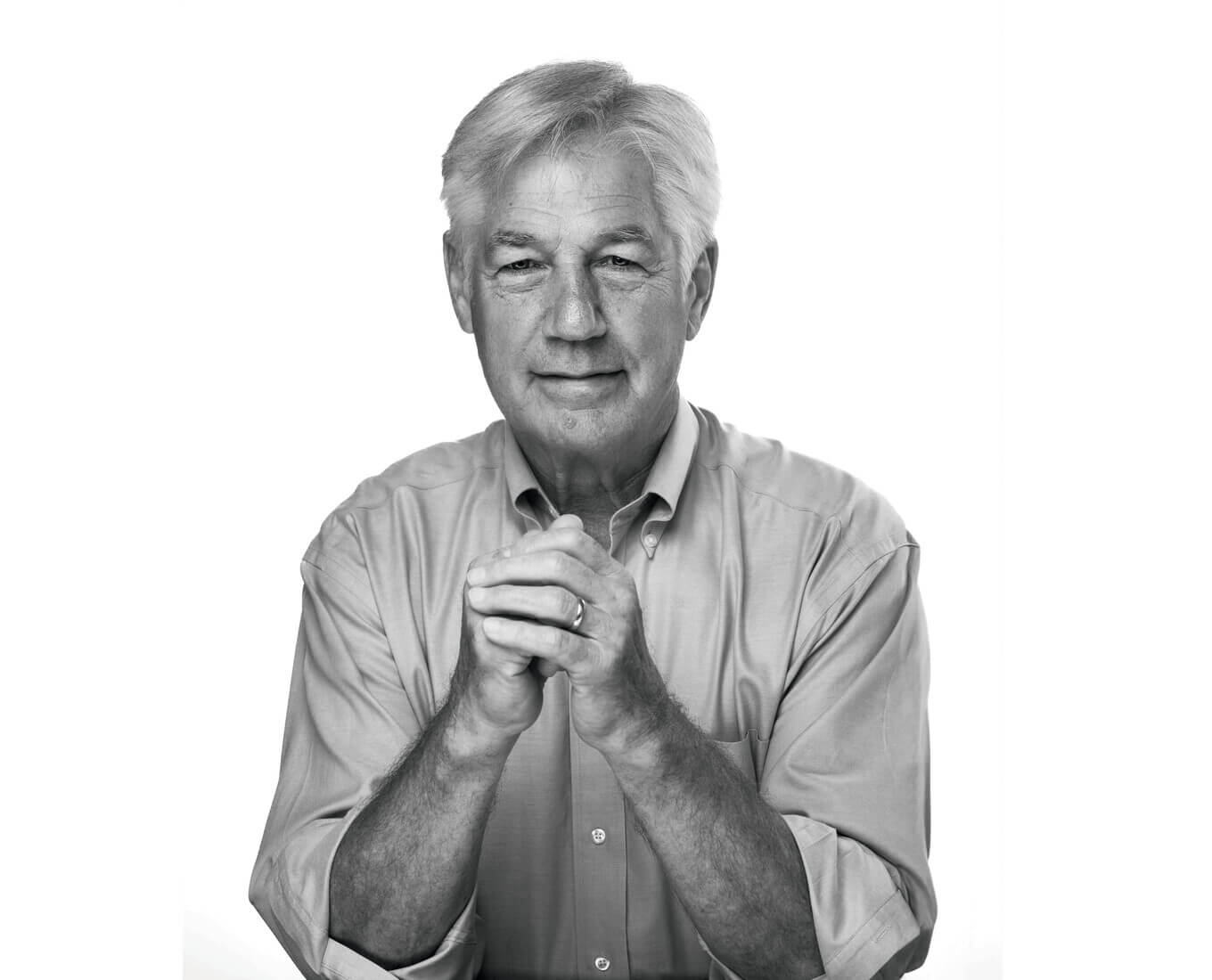

Amid all the activity, Mustard Seed co-founder Frank Kartheiser ’72, Hon. ’19 was in constant movement, preparing meals, serving guests and busing tables as he has done for more than 50 years. Now 75, he founded the organization in 1972 with his wife, the late Mary Brenda Norton Kartheiser, scholar-activist Michael Boover and the late Shawn Donovan ’70. Kartheiser is quiet, discreet and solicitous in the way a maître d’ at a five-star restaurant would be.

“He lives the Gospels; he lives Jesus’ message,” Bushey notes. “Sometimes we have guests that cause problems, and sometimes we want to ban people because of the way they behave — and we do. But Frank's message is, ‘The only thing I know that works is love.’”

Kartheiser makes you want to be a better person, Bushey says, calling him the very model of Catholic Social Teaching (CST). The inclination is to agree vigorously, but to what, exactly?

“CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING IS AN ORIENTATION”

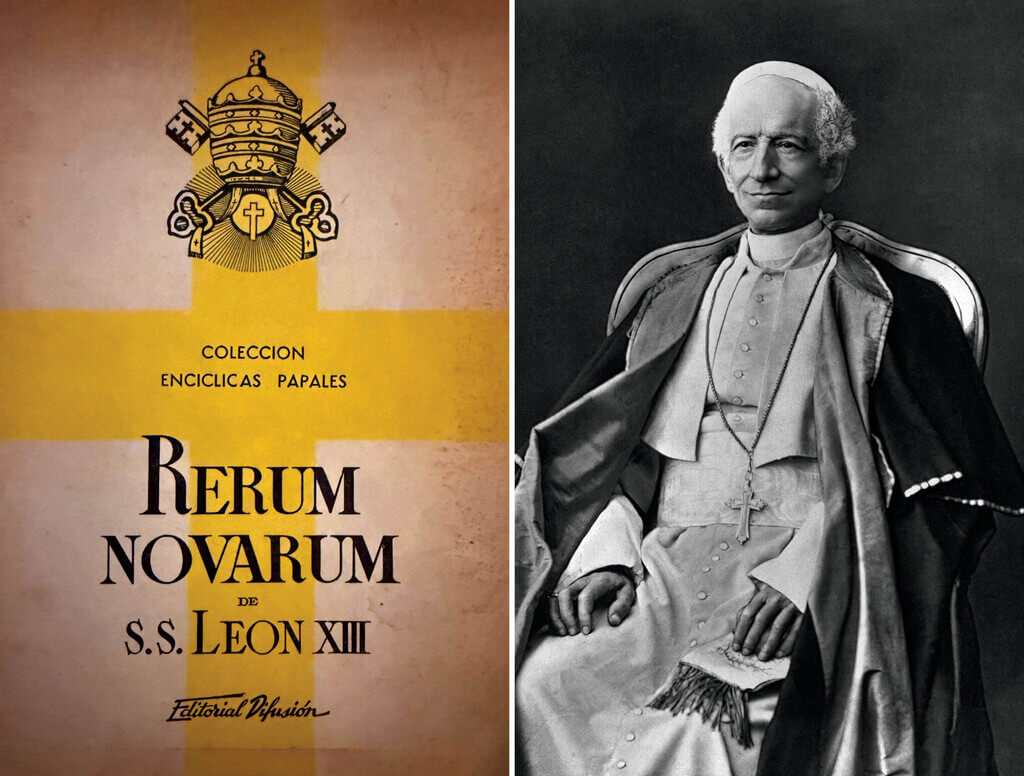

Rooted in the ministry of Jesus Christ, the foundation of CST was laid in 1891, when Pope Leo XIII published an encyclical (a papal teaching document) titled “Rerum Novarum” (“Of New Things”). The letter was a response to the particular historical moment — the advent of the Industrial Revolution — and addressed workers’ rights, economic inequality and collective responsibility, among other labor-related topics.

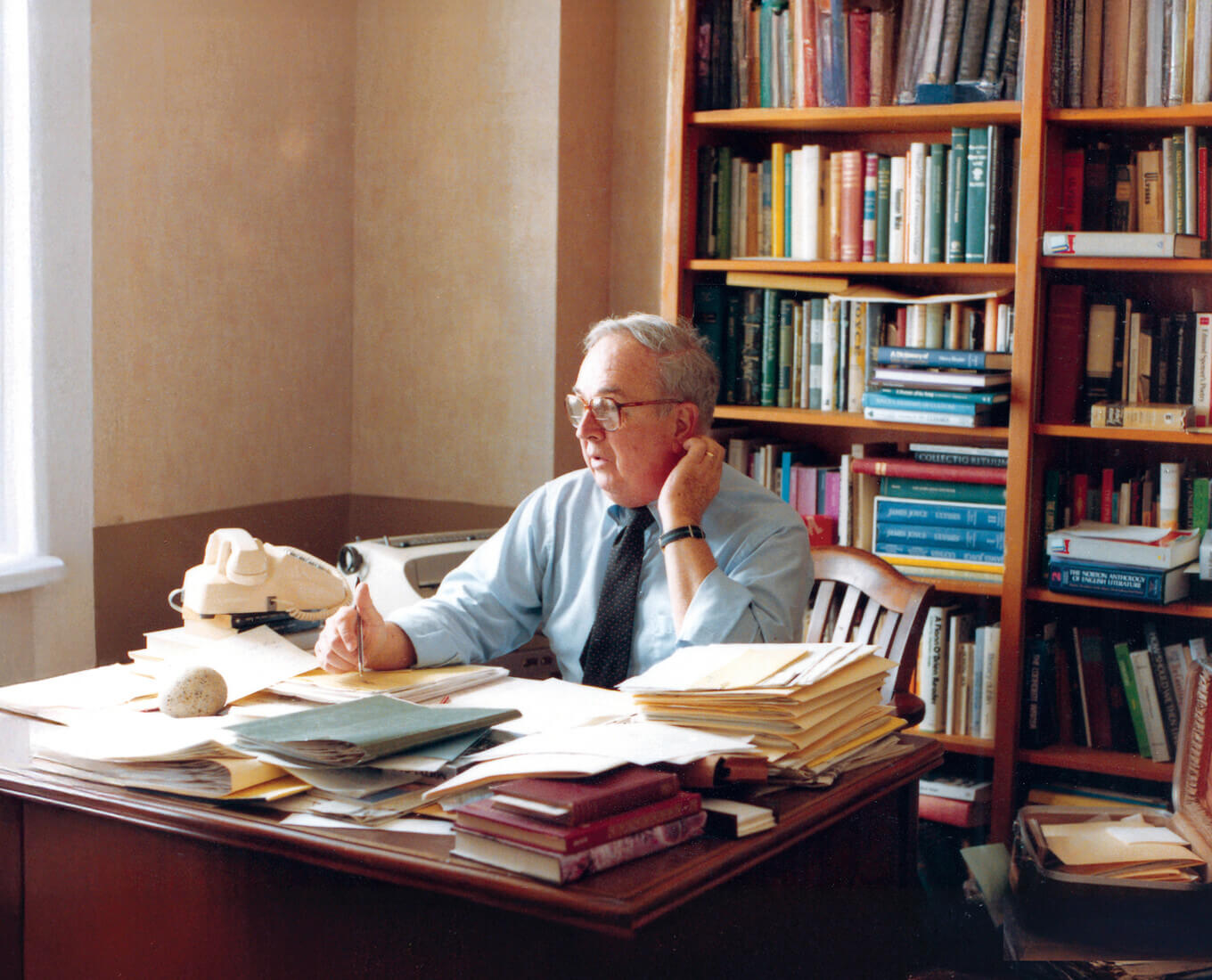

Justin Poché is an associate professor in the College’s history department. In teaching CST, Poché begins with an examination of the pressures placed upon society by three events that made the 19th-century American Catholic Church a church of the working class and the poor: the unregulated rise of industrial capitalism, the rise of socialism in Europe and the mass migration of various European ethnic groups to the United States. Before “Rerum Novarum,” the Church had not taken a definitive stance on labor relations and the rights of workers, Poché says.

“But the Church saw an urgent need to position itself on the side of the laboring classes and the poor. ‘Rerum Novarum’ was quite a paradigm shift in terms of the Church’s position, but it’s rooted in the realities facing most of its members,” Poché says. “Catholic Social Teaching is defensive in response to the rise of socialism, but it also condemns the abuses of capitalism and the exploitation of workers.

“It carves a middle path that both protects the right to private property, while also calling for interventions to both address the miserable conditions in which the majority of workers lived and promote the common good of all people,” he continues. “I think that’s why the modern pope chose the name he did, because he’s seeing how, once again, technology might undermine the rights of laborers and worsen the material inequalities that threaten human dignity and solidarity.”