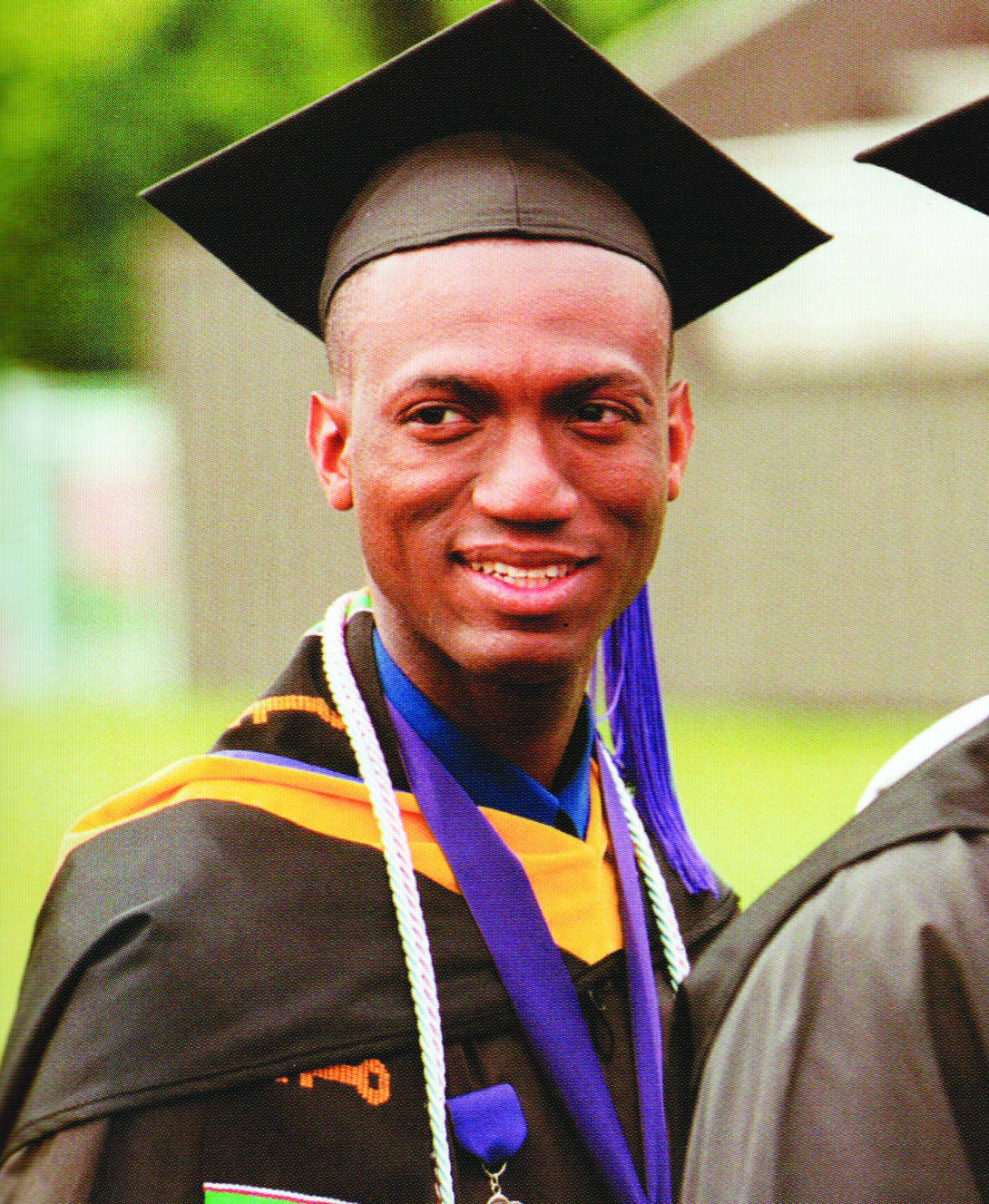

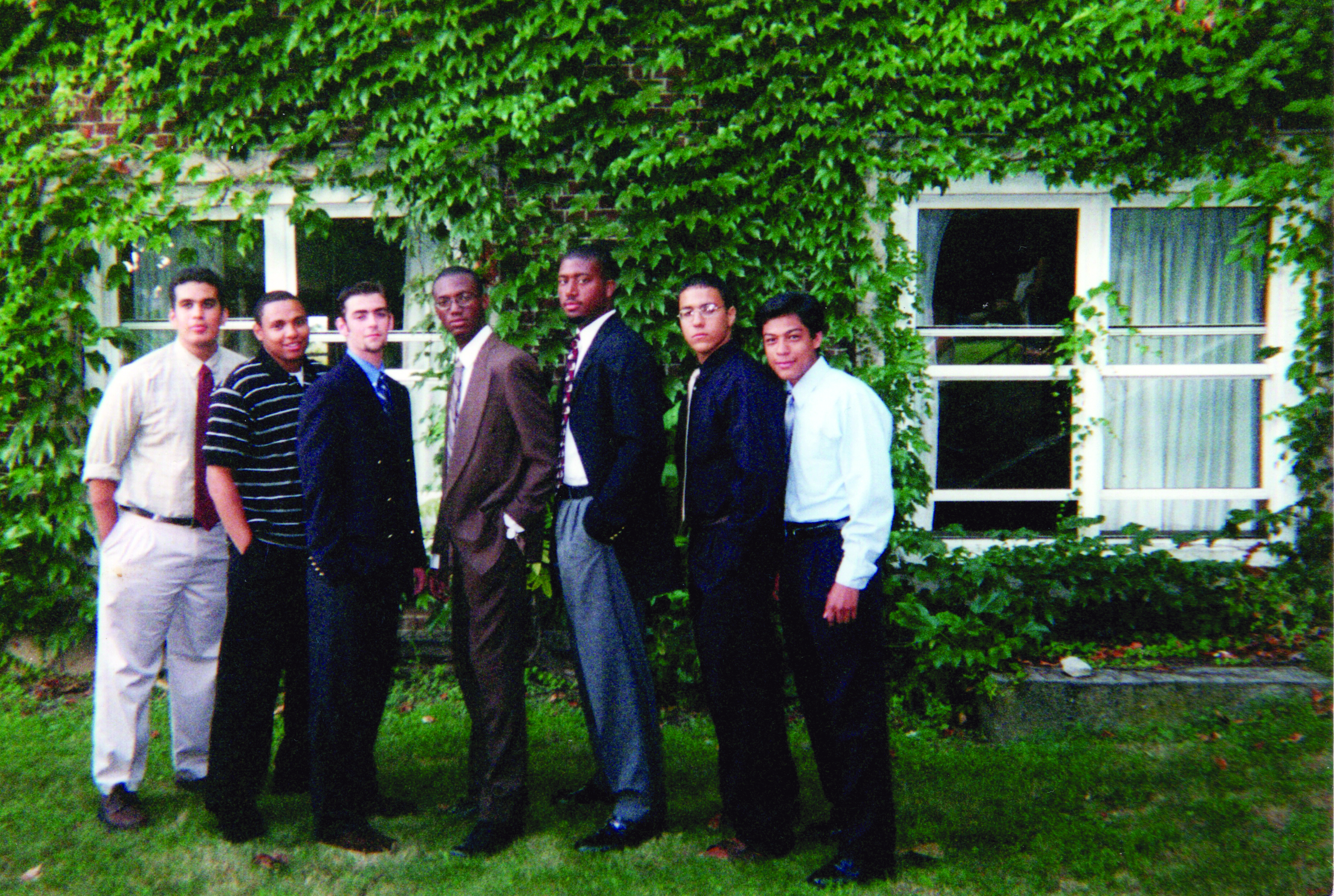

Within mobile devices, the nearly 1 million social media followers of André Isaacs ’05 see a proud, confident, gay Black man. In the nation’s capital, the First Lady saw an inspiration, inviting him to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue for an exclusive watch event for this year’s State of the Union address. At grocery stores, restaurants or anywhere else across the world, fans of the Holy Cross associate professor of chemistry approach him looking for advice on how to find success.

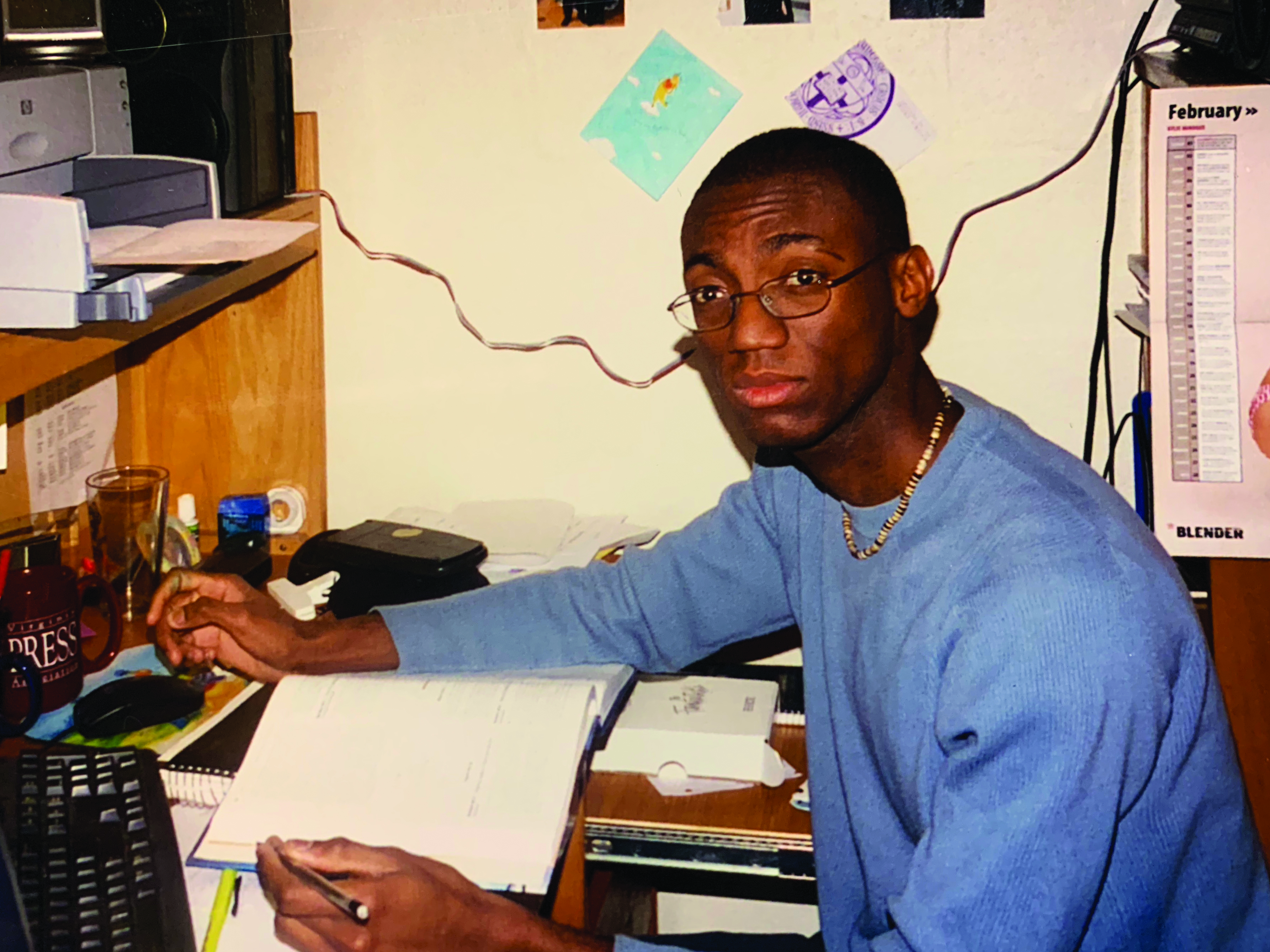

They believe that just like the complex chemistry equations he solves effortlessly, he, too, has resolved the problems and self-consciousness that come with imposter syndrome.

To those closest to Isaacs, they see a more complete version of the man: one who hasn’t solved life’s obstacles and who, like most folks, continually battles demons of the past. A man who naturally connects in uncanny ways with everyone he meets, creating an atmosphere of joy and belonging. They also see and hear the racist and homophobic barbs that he’s dealt with his entire life, which have recently evolved into death threats.

They see the chemist who has become a catalyst for generations of future scientists. But they also know the pain that lingers inside, after the family member who inspired him was violently taken from this world.