"First, let me ask this question: Have we Jesuits educated you for justice?"

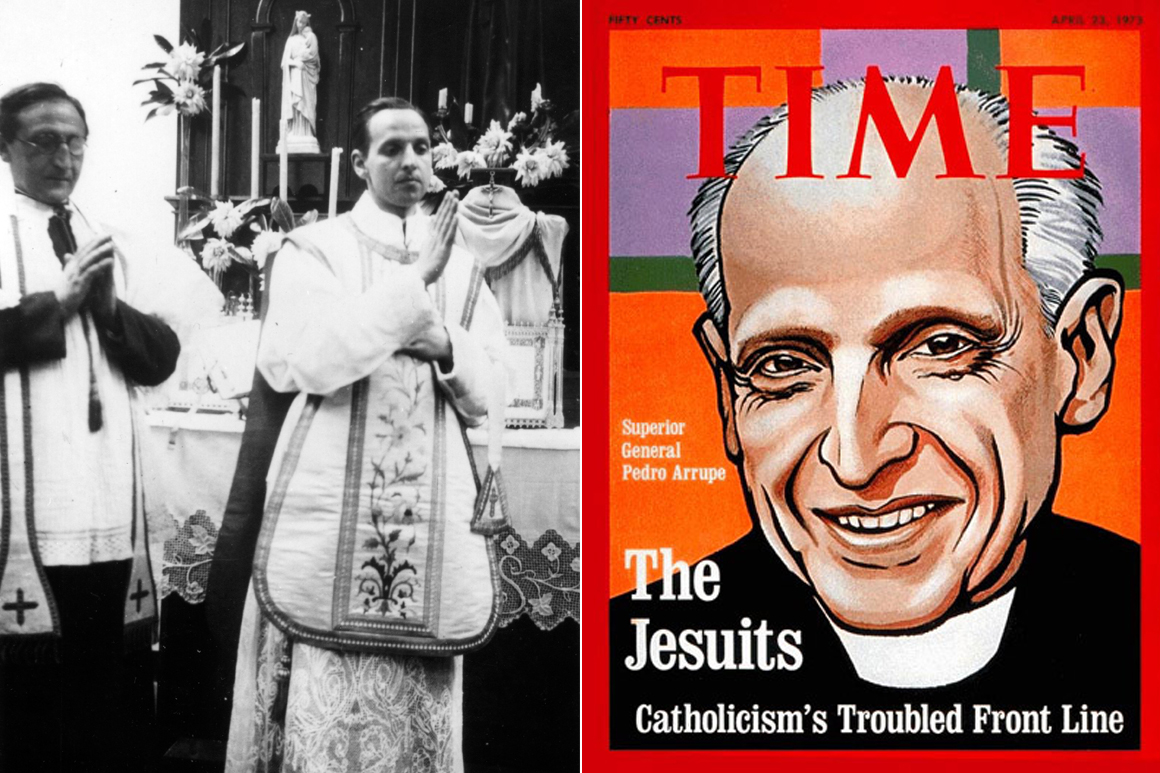

On July 31, 1973, Rev. Pedro Arrupe, S.J., superior general of the Society of Jesus, stood before a large group of Jesuit-educated alumni gathered at a conference in Spain and posed this question. The answer, he said as the room grew tense, was: "No, we have not."

To the alumni seated before him (all men at that time), Fr. Arrupe called for Jesuit education to put a renewed focus on what he coined the formation of "men for others." Graduates should be "completely convinced that love of God which does not issue in justice for others is a farce," he frankly stated.

Fr. Arrupe called on the audience to "live much more simply … draw no profit whatever from clearly unjust sources … and be agents of change in society: not merely resisting unjust structures and arrangements, but actively undertaking to reform them." He had great hope they could do this, he encouraged, because Jesuit education, despite its failings, had always emphasized "openness to new challenges." He promised to work alongside them to change, like two classmates "sitting together on the same school bench."

Many were shocked by the speech, given on the annual feast day of St. Ignatius. Some even quit their alumni associations. But, ultimately, Fr. Arrupe was proven correct that Jesuit education, if nothing else, had instilled a willingness to adapt. Today, the phrase "men and women for and with others," which evolved from that 1973 speech, is ubiquitous in Jesuit education. It has profoundly shaped the more than 3,700 Jesuit schools and higher education institutions that exist around the globe, including Holy Cross. Ask Jesuit-educated students or alumni to describe the aims of their education, and chances are good that phrase will be uttered. And it is one that continues to prompt deep conversations about the moral obligation to create a more just world.

Fr. Arrupe’s first Mass, celebrated in Valkenburg, Holland, in 1936; on the cover of TIME Magazine on April 23, 1973.

Fr. Arrupe’s first Mass, celebrated in Valkenburg, Holland, in 1936; on the cover of TIME Magazine on April 23, 1973.

Arrupe: Second Founder of The Jesuits

"There's a commitment that Arrupe shows in his speech to not being afraid to ask serious and probing questions about ourselves and the goal of our education and society," says Rev. Timothy O'Brien, S.J., '06, associate vice president for mission at Holy Cross. "Part of what he was encouraging was a spiritual discipline of unflinching self-examination that is still with us. The enduring weight or power of this question is precisely that we're not done yet."

To speak this way was shocking, Fr. O'Brien says of the 1973 speech: "Fr. Arrupe was speaking to a room full of people educated by Jesuits in Europe, in schools that often drew from the privileged, wealthy elite. He was asking the privileged to challenge their own privilege — that still has a lot of resistance today. He was calling people to a critical examination and a real clarity about what it means to be educated by the Society of Jesus."

Born in 1907, Fr. Arrupe, like St. Ignatius, was from the Basque region of Spain. A top medical student, he left training to become a Jesuit and was a missionary in Japan when World War II began. As a foreigner, he was arrested on suspicion of espionage. After 33 days, he was cleared and released, with the time in solitary confinement only deepening his faith. In 1945, he witnessed the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima and used his medical training to treat survivors in the aftermath at his novitiate just outside the Japanese city.

In 1965, Fr. Arrupe was named superior general, the highest office in the order, and tasked with guiding the Society of Jesus following Vatican II, which represented a seismic shift in the Catholic Church. "Vatican II was a moment of the Church opening to the modern world, rather than positioning itself in opposition to it, and Fr. Arrupe was the Society's standard bearer in that process," Fr. O'Brien says. "People often refer to him as 'the second founder of the Society of Jesus.'"

Today, "for and with others" is so entrenched at Holy Cross that it's often considered a motto of sorts or even (falsely, albeit understandably) attributed to Ignatius himself. When meeting with students during orientation in the fall, Fr. O'Brien says many expected to see the phrase in the College's mission statement: "That speaks to what they think they're doing here and who we are trying to form them to be."

Words to live by at Holy Cross

"Arrupe's speech has shaped Holy Cross profoundly," says Marybeth Kearns-Barrett '84, director of the Office of College Chaplains, noting that it planted a seed linking faith and justice. "Schools were particularly fertile soil for his message because young people are looking for meaning and purpose in their lives." As a student at Holy Cross in the early 1980s, Kearns-Barrett says the phrase itself was relatively new. "I first encountered it on the Spiritual Exercises retreat," she says. "We still make Fr. Arrupe's speech available for people on the Exercises."

While "for and with others" may have taken some time to become fully entrenched, it captured something long in the air at Holy Cross, Kearns-Barrett says. In 1973, at the time of Fr. Arrupe's address, students had already been serving the greater Worcester community for five years through Student Programs for Urban Development (SPUD). "The civil rights movement and the women's rights movement were shaping the College," she notes. "We also had this great tradition of [Rev. Robert Manning, S.J.'s Theology of Liberation course] being taught here. And our Chaplains' Office and the religious studies department have long emphasized the inextricable link between faith and justice."

Holy Cross is historically one of the country's top producers of graduates entering the Jesuit Volunteer Corps and typically sees 7% to 8% of graduating classes commit to full-time service programs like JVC. Alumni age 50 and older are also consistently well-represented in the Ignatian Volunteer Corps.

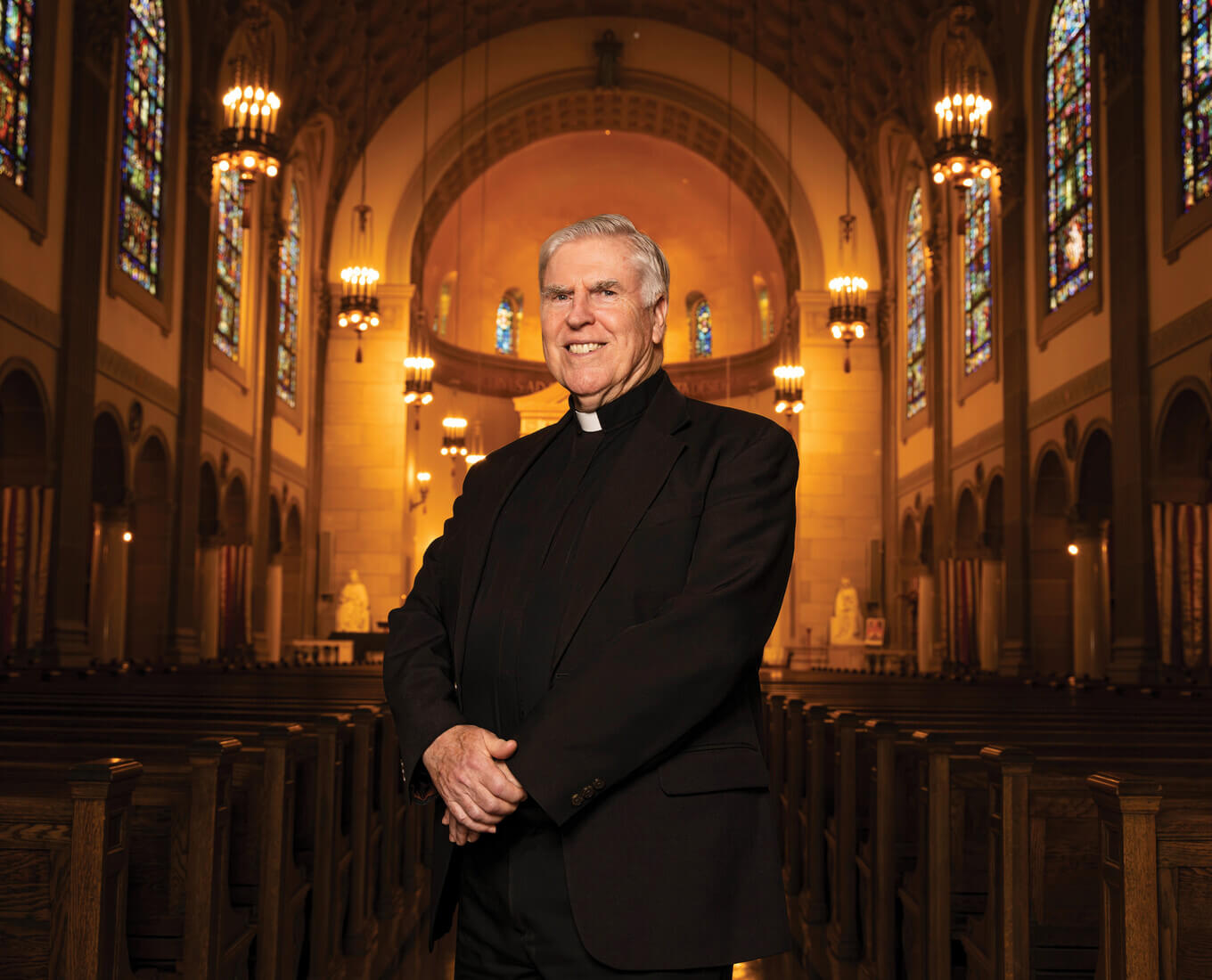

The Very Rev. Joseph M. O'Keefe, S.J., '76, provincial of the USA East Province of the Society of Jesus, describes his years as a Holy Cross student in the 1970s as the "Arrupe era" — an experience that ultimately led him to his vocation. "The thing that sticks out in my mind is the orientation of faith that does justice. Whatever you're involved in: How do you build up the common good? How committed are you to the community you live in? It's a generosity of spirit and a profound care for other people."

Fr. O'Keefe says, at its best, "for and with others" impacts how people live their careers. For example, how do leaders treat their employees? For 25 years, Fr. O'Keefe taught future educators and policymakers studying education at Boston College, and Fr. Arrupe's words guided his formation of these professionals. "Jesuit education doesn't just prepare people to make a living," Fr. O'Keefe says. "It prepares people to make a life of purpose, a life worth living."

He sees aspects of Fr. Arrupe's legacy alive in today's Church. Pope Francis often visits Fr. Arrupe's grave, and Fr. O'Keefe says there is a deep consistency of message between the two men: "There is a focus on what it means to live out your faith." Fr. O'Keefe imagines that Fr. Arrupe, if alive today, would support the pope's stance on climate change and its threat to the Earth and those on the margins: "Arrupe was a man who could read the signs of the time … Being in Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped had such a big impact on him in terms of his commitment to faith, justice, peace and an end to war.

"In a world and a culture that is so deeply divided, [Arrupe's words challenge us] to be with others — and to be with those with whom you don't necessarily agree," Fr. O'Keefe continues. "How can we focus on the common good and building a more just society?"

Fr. Arrupe with Mother Theresa in 1982 in Rome.

Fr. Arrupe with Mother Theresa in 1982 in Rome.

A message that continues to challenge

Fr. O'Brien cautions against simplifying Fr. Arrupe's words into a compartmentalized focus on service, which risks losing some of their original meaning: "As my own journey in the Jesuits and Jesuit education has continued, there's a much deeper realization that the idea of — 'I come to you and serve, then I go back to my enclave of privilege and feel good about having served' — is not helpful."

In alignment with the Jesuit tradition of self-examination, the phrase has evolved, and continues to evolve, with the times. "It has taken on a life of its own in the networks of Jesuit education," Fr. O'Brien says. Today, it is commonly followed by the words, "and with," forming the longer phrase, "for and with others." "This puts an emphasis on solidarity, rather than on a savior complex," he explains.

"There's something about the way the phrase can be adapted that has made it stick," Kearns-Barrett notes. "For example, some of our students are beginning to ask us to say, 'people for and with others' or 'people for and with creation.' Ultimately, the phrase reminds us that Jesuit higher education isn't just for ourselves. Instead of giving us a claim on the world, our education gives the world a claim on us."

"There is a deep hunger among our students for the education that they're receiving on this hillside to be relevant not just to themselves, but to the world and to its challenges," Fr. O'Brien reflects. "And there is a deep idealism, a deep hope, in our students that realizes they will be the source of future progress in the world for justice. In the face of so many challenges, I think they find in Arrupe's phrase a simple way of expressing that desire."

Written by Meredith Fidrocki for the Winter 2023 issue of Holy Cross Magazine.