Acconci: The Student

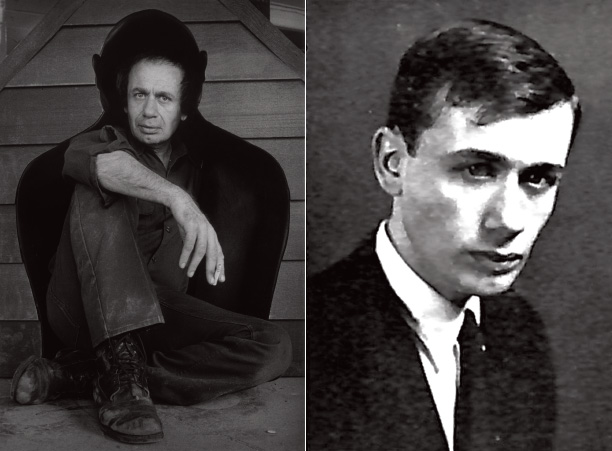

Edward F. Callahan, professor emeritus of English who taught at Holy Cross for more than 30 years until his retirement in 1990, first encountered the young Acconci in his own classroom in 1959.

It was the late 1950s when Rev. Thomas Grace, S.J., then-head of the English department, and I realized the talent and promise of Vito Hannibal Acconci, a novice freshman. The following four years I worked with him, and the 50 ensuing years of witnessing his achievement, were one of my outstanding joys about teaching at Holy Cross. How fondly I recall sharing his devotion to Shakespeare, Joyce, Toscanini, Galileo, Ferlinghetti, Warhol. Encouraging and controlling the Acconci talent and creative adventures were the redeeming challenges of the profession.

His sartorial preference for black clothing and enigmatic prose style were often misleading and at times could be frustrating, but my wife and those who appreciated his work insisted on his promise: He possessed the gentile modesty of a true gentleman, an Italian artist. He was a rebel in prose and poetry, as well as performing art and architectural design.

He represented the United States at least twice at the Venice Biennale and held a gallery show of inflated dolls at the Wagner Palazzo in Venice. He designed the lounge in the Coca-Cola Company headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, and was the focus of a gala show at Manhattan's MOMA.

I recall with pride my visits to Acconci’s Murinsel in Graz, Austria, a floating platform with footbridges that connect the banks of the Mur River. He was ever eager to meet any challenge of design to expand the dimensions and excitement of modern art. My travels to Santa Monica, Montana, Chicago, New York, Venice, Bruch and Worcester were cachets for being associated with his Holy Cross.

To adapt Hamlet: “Rest. Rest, Thou Restless Spirit.” Welcome Home!

Acconci: The Artist

Virginia Chieffo Raguin, distinguished professor of humanities, and head of the art history division in the Department of Visual Arts, has taught at Holy Cross for more than 40 years.

Vito Acconci was one of the most important innovators in modern art, not simply in the United States, but on a world stage. He would object to the term “art” because he was initially drawn to verbal creativity — not the seen or tangible — and “art” in his school years seemed relegated to things passed from owner to owner.

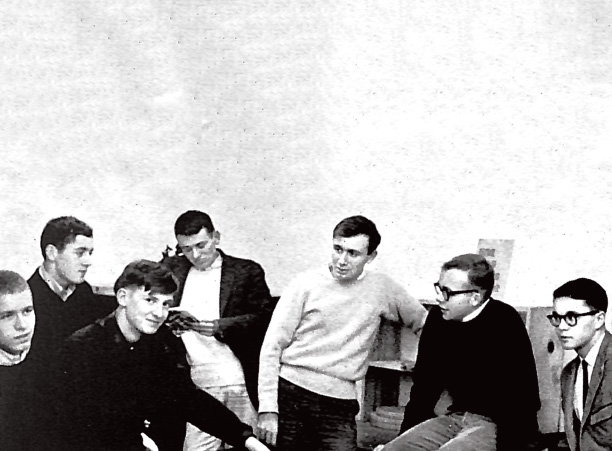

Acconci (third from right) stands with the rest of the 1962 The Purple staff. He served as the co-editor of the campus literary journal. Photo courtesy Holy Cross Archives and Special Collections

Acconci (third from right) stands with the rest of the 1962 The Purple staff. He served as the co-editor of the campus literary journal. Photo courtesy Holy Cross Archives and Special CollectionsArt for Acconci was unsettling, even fearsome, and never pretty. In a modern world of blasé viewing, a sure method of dialogue is surprise — and even shock. In the late 1960s, he was a pioneer leading up to the notorious "Seedbed" of 1972 at the Sonnabend Gallery in New York City. There for a specified time, he engaged the visitor through voiced sexual fantasies. The event has been described as one of the most important live artworks of its era.

Acconci took on architectural constructions in the 1980s, and in 1983 made his first permanent installation as a visiting artist at Middlebury College in Vermont. Ever the man on the edge, Acconi’s Way Station I (Study Chamber) made waves. Reactions were strong, and vandals set it on fire in May 1985. The situation caused some soul-searching about what education was actually accomplishing and in 1994, Middlebury began allocating 1 percent of the construction cost of new buildings to public art on campus, and even reconstructed Way Station in 2013. Shortly after completing his work at Middlebury, Acconci’s interest in sculpture, installation and their intersection with architecture led to his founding Acconci Studio, a collaborative enterprise where designers, sculptors, architects and engineers come together. Playful, iconoclastic and sensually diverse, the Studio’s production of buildings and interiors are worldwide.

Never repetitive or commercial, ever searching and open, Acconci might be considered an artist who never ceased being a student.

Acconci: The Inspiration

Fifteen years ago, Rachelle Beaudoin '04 was a studio art major studying at Holy Cross. Today, she’s a lecturer at the College’s Millard Media Lab in the Department of Visual Arts. She’s also an artist who uses video, wearables and performance to explore feminine iconography and identity within pop culture.

It’s 2001 or 2002, and I’m a sophomore in Digital Art 1 or Digital Art 2. I can’t remember those details now. I do remember and will always remember what I felt when I saw Vito Acconci’s work for the first time. A grainy videotape reveals a man’s hand trying to open the eyes of a young woman who’s resisting, squirming and trying to close her eyes with all of her strength.

Professor Alexandra Opie plays the piece, "Pryings (1971)," by Vito Acconci and Kathy Dillon, without commentary for its entire duration — 17 excruciating minutes. I’m physically uncomfortable. I’m angry and feel like I have just endured the piece myself, as if those are my eyes. Professor Opie then reveals that this artist, Vito Acconci, went to Holy Cross. I exchange glances with Sean, a friend and senior on the swim team. Until this moment, I have been comfortable with my definition of art and my ability to make art; my ability to render realistic fruits, flowers and portraits; my ability even to abstract forms and consider color relationships. But now, a new world has opened up. I can see that art doesn’t only have to be pleasant and pretty and hang over your couch, but it can also be visceral, metaphorical, challenging and even upsetting. This is a seminal moment for me.

It’s 2011 and I am back on The Hill — but now I am teaching Digital Art 1 and Digital Art 2. Dave Matthews Band blares out of the dorm windows and I wonder what year it really is. It’s a strange feeling, being back, and I think often of Vito Acconci’s work and its impact on my own artistic development. In graduate school I started to create performance art clearly influenced by Acconci. I decide to begin writing him letters, as an art piece in itself, and send them to his studio. The letters are diaristic, banal and occasionally philosophical.

It’s 2017 and I am taking my lunch outside on a bench near the Millard Art Center on what seems like the only sunny day we’ve had this semester when I see on my Facebook feed that Vito Acconci has died. At the start of my next class, Digital Art 1, I show "Pryings" — but first tell the class that this influential artist has just died. Watching the video, they squirm, like Dillon. I even hear an uncomfortable giggle, the kind of laugh that arises from uneasiness. This radical and influential artist, I reveal at the film’s conclusion, attended Holy Cross.

I know my students won’t all become performance artists, but I’m still compelled to expose them to it. The experience of being challenged, upending what you thought you knew, the experience of being comfortable with discomfort — that is the gift of Vito Acconci’s work.

About Holy Cross Magazine

Holy Cross Magazine (HCM) is the quarterly alumni publication of the College of the Holy Cross. The award-winning publication is mailed to alumni and friends of the College and includes intriguing profiles, make-you-think features, alumni news, exclusive photos and more. Visit magazine.holycross.edu/about to contact HCM, submit alumni class notes, milestones, or letters to the editor.