English Professor Paige Reynolds’ reading Kathleen Woodiwiss’ 1972 bestselling romance novel “The Flame and the Flower” at the tender age of 12 could be called a crime of opportunity.

Her mother, an avid reader, left romance novels lying around the house, “The Flame and the Flower,” among them. Reynolds took the racy novel with her on a weeklong vacation, sans parents, to her grandmother’s house. There wasn’t much to do there, she says by way of explanation — or exoneration.

Reynolds’ grandmother noticed her choice of reading material:

“Does your mother know you’re reading that?”

“No, ma’am,” Reynolds replied.

“Well, I won’t tell,” her grandmother said. “But don’t let her catch you.”

Reynolds laughs at the memory, noting that until recently, reading romance was treated by many as a covert activity, something to hide because these books were considered frivolous, dumb or even a corrupting influence. Her youthful transgression remains a vivid memory, but she rejects the idea that reading romance is something to be done surreptitiously or apologetically. Reynolds has published extensively on Irish women writers, most recently in her 2024 book, "Modernism in Irish Women's Contemporary Writing: The Stubborn Mode." This advocacy for women writers continues in her consideration of romance fiction, which has been maligned in large part, she argues, because it most often has been written by women writers for women readers.

Reynolds is uniquely qualified to make the argument; she’s not only a scholar but also an avid fan. During the darkest days of the Covid pandemic, Reynolds turned to romance fiction for its predictable pleasures and found herself briefly ranked on Kindle as among the top 1% of readers of romance worldwide.

“I’m an expert in romance fiction now, I guess,” she says and grins.

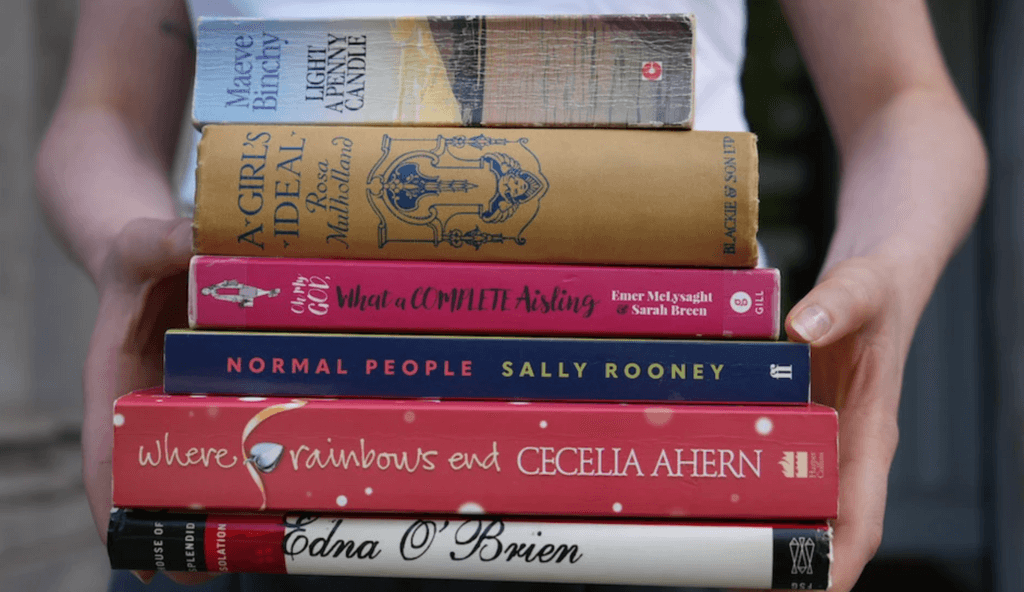

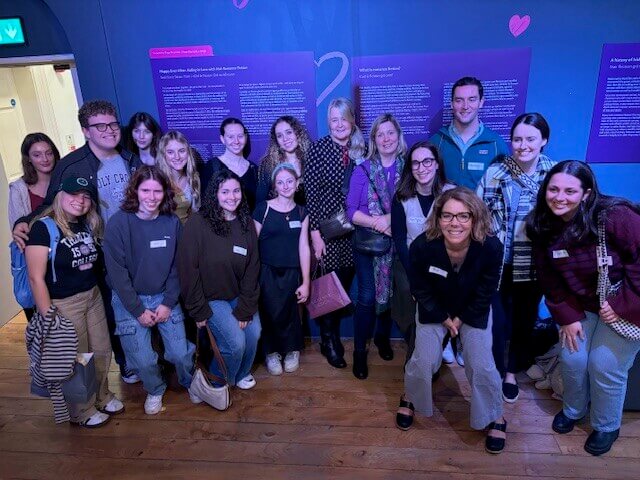

Reynolds' enthusiasm for romance is on full display in “Happy Ever After: Falling in love with Irish romance fiction,” an exhibition centered on the long history of Irish romance fiction currently on view at the Museum of Literature Ireland (MoLI) in Dublin. She curated the exhibition, the first of its kind, which MoLI has twice extended due to its popularity. The exhibition is supported by the Callahan Support Fund for Irish Studies, with the assistance of student researchers on campus through the College's J.D. Power Center for Liberal Arts in the World and in Dublin through the Office of Study Abroad. The exhibition covers centuries of Irish fiction, from "Vertue Rewarded; or, The Irish Princess," anonymously published in 1693, to the novels of present-day literary luminaries Maeve Binchy, Emma Donoghue, Sally Rooney and Marian Keyes. There is a companion "Happy Ever After" podcast, and plans for an online exhibition.

An interesting truth about romance: It has been derided by critics for centuries while simultaneously being the most popular — and profitable — genre in publishing. In fact, romance is a billion-dollar industry whose sales and library rentals dwarf those of other genres. And with the advent of social media, especially TikTok and Instagram, romance has found an invaluable word-of-mouth support system, with enthusiastic influencers plugging the work of their favorite romance writers. Romance has seen such a surge in popularity in recent years that independent brick-and-mortar bookstores devoted exclusively to romance have opened up in many major U.S. cities with names such as Meet Cute Romance Bookshop (San Diego), Under the Cover (Kansas City), The Ripped Bodice (Brooklyn) and Lovestruck Books (Cambridge).

Romance is due its happily ever after

In “Happy Ever After,” Reynolds uses her scholarly clout to argue that romance literature deserves the same degree of thoughtful critical attention awarded all other forms of literature, including other popular categories like crime, horror and science fiction.

Romance is formulaic: people meet, encounter and overcome obstacles, and end up in a relationship, their "happily ever after" or their "happy for now," Reynolds says. She insists that familiarity needn’t breed contempt: "Like all forms of literature, romance novels can be great, okay or terrible."

But the best representatives of the genre, she says, vividly reflect the values of their contemporary moment and allow readers to share in the optimistic possibilities of a 'happily ever after' — even when working within the boundaries genre superimposes on story.

“By awarding Irish romance fiction the serious consideration it deserves, [the exhibition] hopes to transform ‘romance’ into a neutral descriptor, one that generates as little adverse friction as labels like ‘French fiction’ or ‘nature writing,’” Reynolds wrote in a 2025 piece for the "Irish Times" titled, “Why Irish romance fiction deserves its happily ever after.’

And don’t forget that some works of literature that routinely show up on college and university syllabi are inherently romantic tales by writers so famous we refer to them in a last-name-only shorthand — Austen and Brontë are just two examples, and the many film adaptations of their romances attest to the enduring popularity of these stories. Reynolds seeks to expand and diversify that list by showcasing Irish writers, from Lady Morgan ("The Wild Irish Girl," 1806) to Anna Carey ("Our Song," 2025).

Speaking of the Brontë sisters, Reynolds shares that she was also reading “Jane Eyre” — "the first, big, serious adult book I could not put down" — at around the same age she was introduced to “The Flame and the Flower.” Historical romances were her favorite, she explains. Reynolds notes that "The Flame" and "Eyre," a commercial "bodice-ripper" and a celebrated literary masterpiece, respectively, both depict gender, sexuality, race and class in ways that today's critical readers recognize as deeply problematic.

"Even here," Reynolds asserts, "romance offers us a positive lesson: Re-reading these books for the exhibition allows us to see productive ways in which our culture and its attitudes have evolved since these romances were published.

"Romance may seem like a distraction — a beach read, a guilty pleasure. But it is a valuable tool, particularly in our polarized, digital age," Reynolds says. "Many of these books allow us to witness how healthy interpersonal relationships play out, how people who care about each other work out their problems — both the romantic couple at the center of the narrative, as well as the family, friends, and community that support them."

“By reading romance, you immerse yourself in the emotional lives and relationships of different people,” Reynolds says. “I feel like romance, which depicts the desire for connection and for deep feeling and offers us a glimpse into other people’s fictional relationships, can be really healthy for readers.”

That’s not to say that all romance fiction rises to the level of a “Pride and Prejudice," but viewed on a continuum, romance literature is the story of culture, Reynolds says.

“Even offensive romance fiction is a register of where we were and how far we’ve come,” she says.

And, for the record, readers have Reynolds’ full-throated encouragement to enjoy romance openly.

“I don’t know why we’re so uncomfortable with allowing ourselves joy, as if, somehow, we’re cheating on our political or our social or our ethical, moral, religious or intellectual commitments,” she says. “Feelings and facts can be tethered; pleasure and rigor can go together.”