Matheson has won multiple awards for his teaching and research, co-authored four books and written more than 100 papers. He is sought out big time by almost every national news outlet you can name — and a whole bunch of others you can’t. The last 15 pages of Matheson’s research profile track his media appearances since 1999. The list is single-spaced and incomplete. “It reflects only the appearances that show up on Google News,” he notes.

Also listed is a reference to the amicus brief he co-authored for the U.S. Supreme Court in its Alston v. NCAA case in 2019. That was the 9-0 decision against the NCAA in favor of athletes being fully compensated, at least for their academic expenses.

“Nine-O in today’s Supreme Court,” Matheson says. “How many 9-O’s do you get? Right? While that case didn’t deal directly with the professionalization of athletes or NIL, within a week of that loss, the NCAA saw the writing on the wall and dropped all these prohibitions against Name, Image and Likeness. Within a week.”

Journalist Jürgen Kalwa is a U.S.-based correspondent covering professional sports for several German media outlets, including Deutschlandfunk, German Public Radio, which boasts more than 1 million listeners daily. He first interviewed Matheson in 2012.

Matheson in conversation with CBS News in 2023 about lottery jackpots.

“My stories cover not only major team sports and their leagues, but also major individual sports — plus anything regarding the business of sports, corruption, betting, doping, health, political aspects, etc.,” Kalwa says. “At some point, I began to rely on experts, many of them professors in different fields: law, medical research, public health, economics — and not affiliated with the sports ventures that I cover. Victor has been my favorite expert on the economics of sports because I can always tap into his vast knowledge of everything regarding the financial and economic backbone of sports. He is up-to-date and provides depth and analysis, which is crucial because leagues, managers, agents and athletes paint a rosy picture of whatever they represent or promote.

“Without access to critical thinkers and independent minds,” he continues, “you will never be able to explain the machinations of what has become the biggest category of the entertainment industry.”

It’s no wonder that for the past five years, the economics of sports gambling has had the lion’s share of Matheson’s attention.

Well, that and soccer.

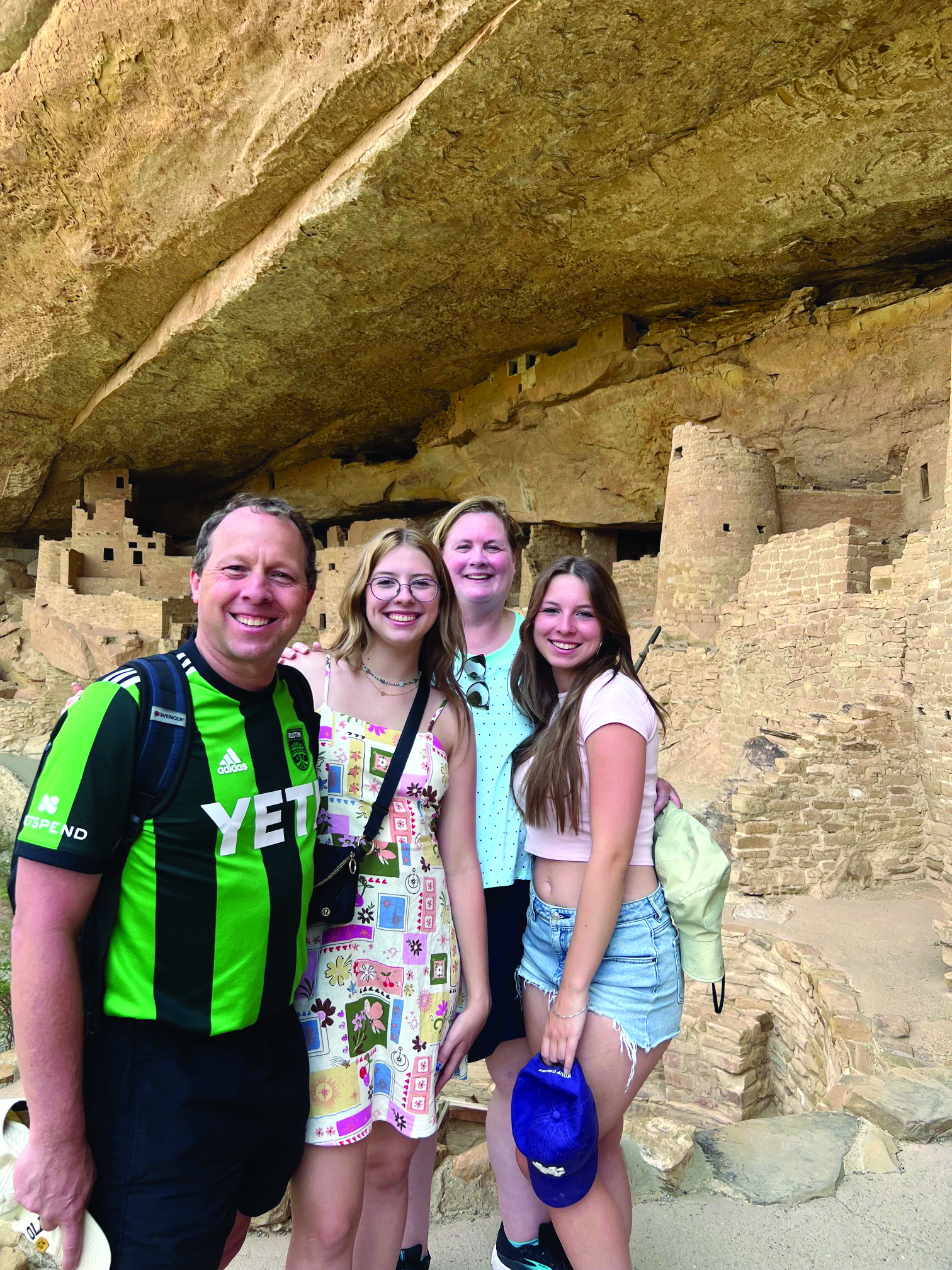

Matheson has lost track of exactly how many soccer jerseys he owns, but knows it's more than 42.

Matheson is a referee for the NCAA and U.S. Soccer. A former Major League Soccer referee, he has officiated college games for the Big Ten, Big East, ACC and Ivy League athletic conferences, among others, since 1988. Since the pandemic, Matheson has worn a professional soccer jersey to work every day. He wore a full uniform — or kit, in soccer parlance — to Provost Elliott Visconsi’s 2024 fall address to the faculty. Like many students, Matheson stands by the idea that shorts are a four-season proposition.

He’s lost track of how many jerseys he has — but it’s more than 42, he knows that much.

“I used to be a shirt-and-tie guy, but it seemed a little silly during Covid to be doing that,” Matheson says. “So I started wearing a jersey every day. And just as something to alleviate the pain of having no human interaction, I did this challenge with my students: I said, ‘I think I’m going to try and wear a different jersey every day and let’s keep track and see if I can do it.’

“On the last day of class, I had to dig deep,” he continues and grins. “The very last jersey I had left was an intramural jersey from my days playing as a faculty member at Williams College. Now I’ve expanded my collection. I can easily go an entire semester with a new jersey every day. I’m never going back.”

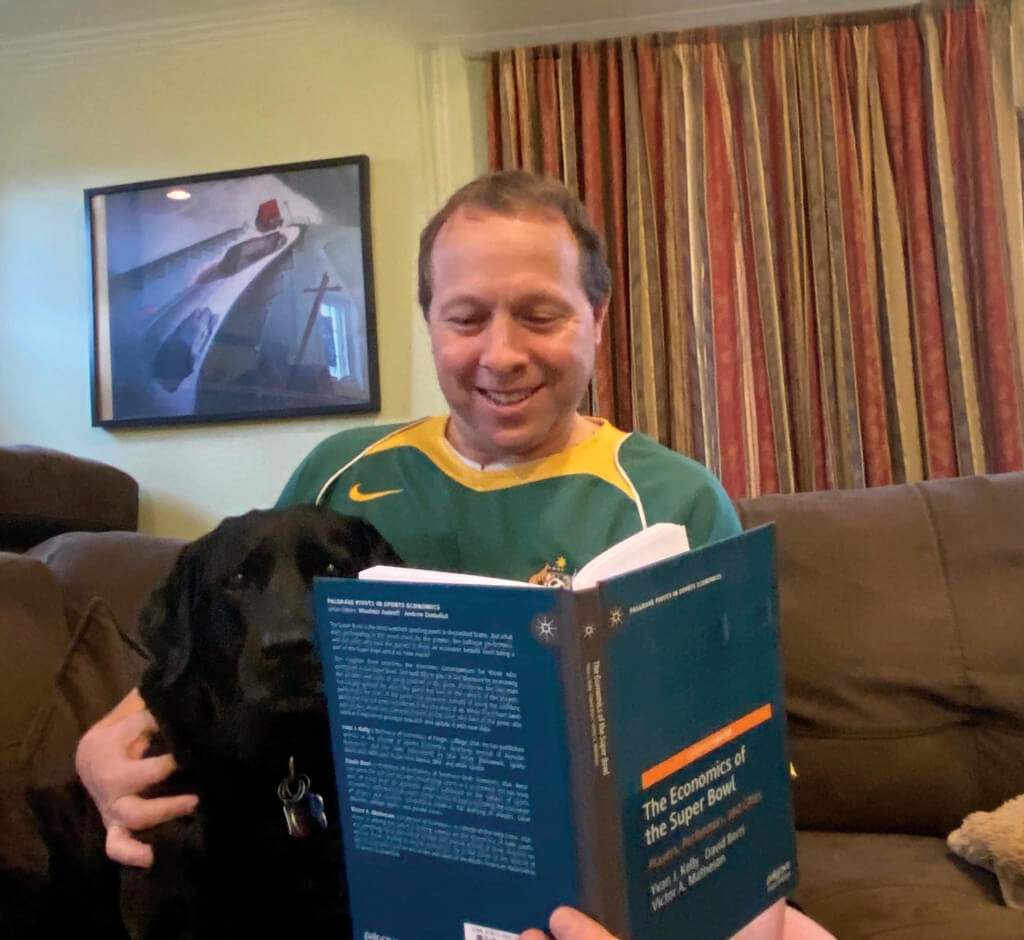

On an unseasonably warm, sunny morning in November, Matheson’s dressed in the maroon jersey of the Qatar National Team, yelling greetings to students over Taylor Swift’s “Shake it Off.” The course is Economics 329, Economics of Sports. The day’s topic is mega-events, which accounts for how the topic of Swift came to be in a sports economics class. The textbook for this course is “The Economics of Sports, Seventh Edition,” by Michael Leeds, Peter Von Allmen and Victor Matheson.

In Matheson’s course, students study econometrics, which is, at its core, mathematical methods to describe and analyze complex economic systems.

A look at pre-COVID Matheson in the classroom, where he sported a more traditional wardrobe: “I used to be a shirt-and-tie guy."

They work with big data sets and consult on products. Complex topics delivered through a mutual love of sports just make good sense, Matheson says.

“Economics in general is looking at the way humans interact and the way they make decisions — but in a quantitative manner,” he says. “One of the great things about sports is you can make it analytical and develop all sorts of important tools using sports as your base, while also explaining it to anyone pretty simply.”

Gambling economics

This spring, Matheson will teach a class on the economics of gambling. A course like this is perfect for a college setting as young, highly educated men are sports betting companies’ top market, while also being among the most vulnerable populations in terms of developing gambling problems, Matheson says.

“Holy Cross is one of the few places in the country that teaches a course in gambling economics,” Matheson notes. “Think about how much interest there is — both from a policy level and a student level. Students are inundated by DraftKings and FanDuel. We’ve got lotteries in 45 states. We have casinos in a similar number of states.”

Callan Whamond ’19 graduated summa cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and economics. She is working on her Ph.D. at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. An avid baseball fan, she took Matheson’s sports economics course in her second year at Holy Cross. The following semester she took macroeconomics with Matheson.

“Professor Matheson brings such energy to his classes, which keeps the lectures engaging,” Whamond says. “In academia, there can be pressure to take yourself very seriously, so I admire how Professor Matheson creates an environment that balances hard work and fun.”

Mountain climbing in New Hampshire with Holy Cross faculty colleagues Miles Cahill, Karen Teitel and John Carter.

Matheson is literally the guy who wrote the book on sports economics, notes colleague and friend Robert Baumann, professor of economics. He and Matheson have been working together at Holy Cross for two decades and have written many scholarly articles together.

“Some call economics ‘the dismal science’ because you present us with something seemingly positive and we’re always throwing cold water on it,” Baumann says. “He wears that as a badge of honor.”

But it doesn’t make Matheson pretentious or dour, Baumann continues. He’s the guy you want to have a beer with, the one who livens up the lunch conversation.

“I think when you encounter Victor you immediately sense his upbeat personality. He’s a fun guy to be around and he’s also a serious academic. And he has this ability to spot research questions that are interesting to people across the board,” Baumann says. “He works hard. He puts a ton of sweat equity into it; that’s the only way you get a research profile like that.”

When preparation meets opportunity. Kinda.

Matheson grew up in an upper-middle-class home in Boulder, Colorado, the only son of a research scientist and an art teacher. He was an outdoorsy kid, drawn to horseback riding and mountain climbing, who loved sports and will proudly tell you that to this day his 84-year-old mother, the aforementioned art teacher, still rides horses. Matheson is a self-described classic high school nerd, though not pocket-protector nerdy — being a varsity athlete (you guessed it, soccer) spared the straight-A student that particular indignity.

He also knew from a very young age how to make a buck. Matheson wholly funded his college education before he’d finished high school.

“My grandfather gave the cousins a little bit of stock in Dow Chemical one Christmas and following its value over time got me interested in finance,” he says. “I had a bunch of stock by the time I was in high school. I had a broker. I’d be, like, ‘I’d like to sell 50 shares of this and buy 50 shares of that.’ And then the broker would call my parents and they were, like, ‘Whatever. He seems to know more about the stock market than we do. Go ahead and do what he says.’”

In his senior year, Matheson sold the entirety of his portfolio, just weeks before the massive 1987 Black Monday stock market crash, and fully funded his undergraduate education at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota.

“The first thing I did there was take an economics course,” Matheson says. “I like that economics was hard, quantitative science, but I also kind of wanted to teach.”