Lucca Eloy "18 didn't arrive at Holy Cross planning to major in computer science. He figured he'd focus on biology, maybe even go pre-med. But a funny thing happened sophomore year after he signed up for a computer science class to fulfill a requirement. As the semester went on, he found himself setting aside his biology homework to start working on computer science projects — the day they were assigned.

"I figured that was a good sign," he says. He even enjoyed taking exams. "I fell in love with the subject."

Eloy ended up switching his major to computer science; not wanting to totally abandon biology, however, he joined the new interdisciplinary neuroscience minor. Working closely with Professor Constance Royden of the mathematics and computer science department, he developed an independent project to artificially model the way the brain processes visual information.

"We programmed these cells to act just like cells in the human brain and respond in the same way," he says. "It's not what you'd expect from a computer algorithm."

The individual attention of a faculty member that comes with studying at a small liberal arts college deepened his interest in the burgeoning field known as computational neuroscience; this fall, he'll enter a Ph.D. program in computer science and cognitive science at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

"Having that experience is what opened up the field to me," he says. "If I didn't have that, I probably would never have switched to computer science and been on the research track that I am now."

Movies and television love to traffic in a particular stereotype of computer scientists — complete with glasses, ill-fitting clothes and no social skills — and they aren't exactly the image of a liberal arts college graduate. As computers have permeated every aspect of our culture, however, computer science has taken off as a major at the College, even among students who had no intention of taking a computer science class when they arrived on The Hill.

"Students take a computer science course," says Royden, "and they realize it's very interesting, and so they stay."

Enrollment in computer science classes at Holy Cross has risen to 353 students in the most recent academic year, a significant increase from 134 just five years ago. During that same period, the number of course sections has risen from 11 to 21. Computer science majors at Holy Cross are breaking new ground in other ways, as well — 30 percent are women and 32 percent are students of color.

"There is a stereotype about the culture of computer science, which doesn't appeal to women, of people sitting in dark rooms drinking Jolt cola and being socially awkward," says Royden, adding that the more women and students of color who enter the field, the more she sees that culture changing. "There has to be a critical mass in classes, so people see other people like them around them."

In addition to being diverse demographically, students also vary in the ways in which they are applying computer science in their classes, says Kevin Walsh, an assistant professor in the mathematics and computer science department.

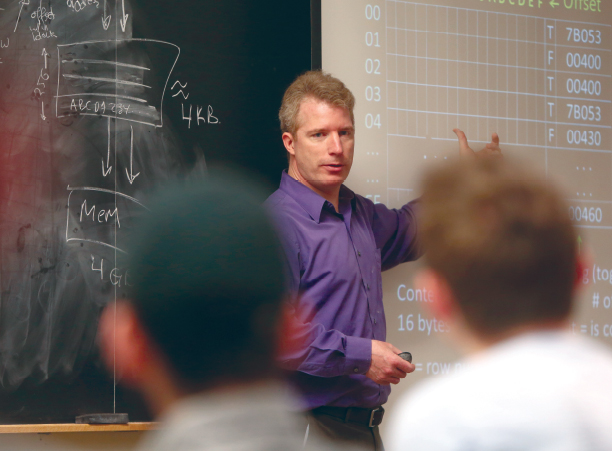

Kevin Walsh, assistant professor of computer science. Photo by Tom Rettig

Kevin Walsh, assistant professor of computer science. Photo by Tom RettigStudying computer science at a liberal arts college rather than a large research university influences the way students approach the subject, Walsh says, giving them a wider context for technological applications. "They notice problems that someone a little more siloed wouldn't have thought of," he says, for example, being aware of how different minority groups might be affected by language used in a particular app.

To drive this point home, every Holy Cross computer science major is required to take a course on technology and ethics, examining real-world issues from the perspective of utilitarianism or deontological ethics. "You look at the way that Facebook has played fast and loose with data, you wish they had had some ethical courses," Royden notes. "We give students tools to think about what are the best pathways to make decisions about things."

Those decisions extend beyond our own country, as well. For the past several years, students of all majors had the opportunity to go to Bangalore — the "Silicon Valley of India"— for a study abroad Maymester program, "Social Justice in Context." The four-week course grapples with the rapid changes technology has brought to the hotspot, both positive and negative.

"On the surface, you think about how it introduces jobs," says Walsh, who led the program in 2015. On a deeper level, however, those jobs have improved women's rights by providing new degrees of independence — and have even affected divorce rates — "now that more women are empowered to leave their husbands," he says. While that kind of empowerment might be positive for some citizens, others are left behind in the slums created by the rapid urbanization of the city and the pollution that tech companies leave behind in the wake of their development.

Emily Vogelsperger '19 augments her work in computer science with her interests in English and Deaf Studies. Photo by Tom Rettig

Emily Vogelsperger '19 augments her work in computer science with her interests in English and Deaf Studies. Photo by Tom Rettig"My code is really well structured and includes lots of comments," she says. "Someone else reading it pretty much knows what I am doing, even without me having to explain it to them."

Her communication skills have also helped her express herself away from the keyboard. Last year, Vogelsperger participated in a Hack-A-Thon at Perkins School for the Blind, where the assignment was to design an app that would help a blind student in a cafeteria setting. As the only student participating from Holy Cross, she joined another group of students from a more technically oriented university; overnight, however, their code broke down and they weren't able to present a working prototype. Even so, Vogelsperger helped prepare a presentation showcasing the idea — a version of Yelp for a dining hall with daily reviews and ratings of food.

"We argued that it would be helpful because everyone would use it, not just blind people," she says. Based on the strength of the presentation alone, the team won runner-up in the competition. "They said we were the ones who thought about how the app would work in the real world," Vogelsperger says.

When applying for internships at tech companies last summer, she similarly discovered that her liberal arts background, far from being a liability, was actually a plus in the eyes of potential employers.

"They always said, 'You can do more than just sit around and code — you can talk to clients, participate in project management, write articles,'" Vogelsperger says. Graduating next year, she hopes to go into project management for a tech company, potentially developing technology to help the deaf or blind communities.

(left) Andrew Lin '98 at Google's main campus in Mountain View, California. (right) Amanda Frederick '96 at work at IBM.

(left) Andrew Lin '98 at Google's main campus in Mountain View, California. (right) Amanda Frederick '96 at work at IBM."I've been told by a lot of people, 'You don't look like a typical software developer, you don't talk like a software developer,'" she says. "Sometimes people get too focused on the technical aspects of the software and don't have the ability to bridge the gap to the business side."

Those skills even extend beyond her immediate company to help her communicate internationally. "We are on conference calls every day with a team in China," she says. Drawing on her liberal arts background, she says, gives her more cultural sensitivity and awareness of the culture of the people with whom she is talking. "Things get lost in translation over emails and texts. Having the soft skills to be able to work with people and come to an agreement when there are different decisions that need to be made and being able to explain yourself while also listening to other people's points of view can be very important."

That same kind of big-picture orientation has helped Andrew Lin '98, who was a physics major at Holy Cross and now works at Google as a hardware engineer. "In my mind, there are two kinds of engineers," he says, "specialists who concentrate on one particular area, and generalists who work on all kinds of different things." As a generalist, he has been able to apply a broader perspective to his work, he says, seeing how systems are integrated and anticipating what might go wrong in complex architectures.

Lin was even able to draw on his physics background early on in his career, when his boss asked him to create a simulator for a digital camera system — despite not having any background in that area.

"He dumped it on me and said, 'You've got to get this done,'" Lin remembers. "I ended up pulling out my old physics textbook and writing up a simulator from first principles. Having a pure science background and that larger understanding allowed me to do something like that, whereas someone with a straight engineering background might not have been able to do that."

Being in a liberal arts environment has also been rewarding for computer science faculty at Holy Cross, say Royden and Walsh, who are not only passionate about teaching undergraduates, but also appreciative of the cross-disciplinary opportunities for research. Royden's research in computational neuroscience, for example, straddles the disciplines of computer science and psychology. In particular, she examines how our brains process motion — how we know, for instance, that an object is moving toward us or away from us when we are moving at the same time.

"Vision is a lot more difficult than most people think," she says. "We just open our eyes, and it makes the whole world available to us. Computer vision has been going on since the 1960s, and we still don't have computers that can see as well as the average 2-year-old." Studying the way our brains process motion might one day help computers better mimic human vision, in applications such as self-driving cars.

As much as liberal arts can influence the study of computer science, however, the transmission works both ways. The kind of logical thinking necessary for successfully implementing computer code can be applied to an array of other problems.

"A lot of computer science is about a computational way of thinking," says Walsh, "learning how to break problems down into smaller pieces and manipulating and organizing data. That way of thinking can bring new perspective to other fields, as well."

As technology becomes more and more part of the vocabulary of everyday life, having a fluency in computer science also seems increasingly essential to being a citizen in today's world.

"On a basic level," says Walsh, "I think it's pretty clear that not knowing how technology works is just not acceptable anymore in modern society." From congressional hearings on Facebook to alleged hacking in the 2016 presidential election, for better or for worse, computer literacy has become increasingly a condition of participation in the modern age.

"Having some computer science is really important to having a full liberal arts education," Royden says. "Computers are so ubiquitous and have such an impact on society, we'll all have to be making policies about self-driving cars and social media. It's very important that even non-computer science majors have the background to make decisions as voters and citizens about how technology is affecting our world."

Written by Michael Blanding for the Summer 2018 issue of Holy Cross Magazine.

About Holy Cross Magazine

Holy Cross Magazine (HCM) is the quarterly alumni publication of the College of the Holy Cross. The award-winning publication is mailed to alumni and friends of the College and includes intriguing profiles, make-you-think features, alumni news, exclusive photos and more. Visit magazine.holycross.edu/about to contact HCM, submit alumni class notes, milestones, or letters to the editor.