He grins at the memory. “It could’ve been something I read in one of my father’s military magazines. It could’ve been something apocryphal, but it made for a good story and they were, like, ‘Yeah, we’re accepting this guy.’”

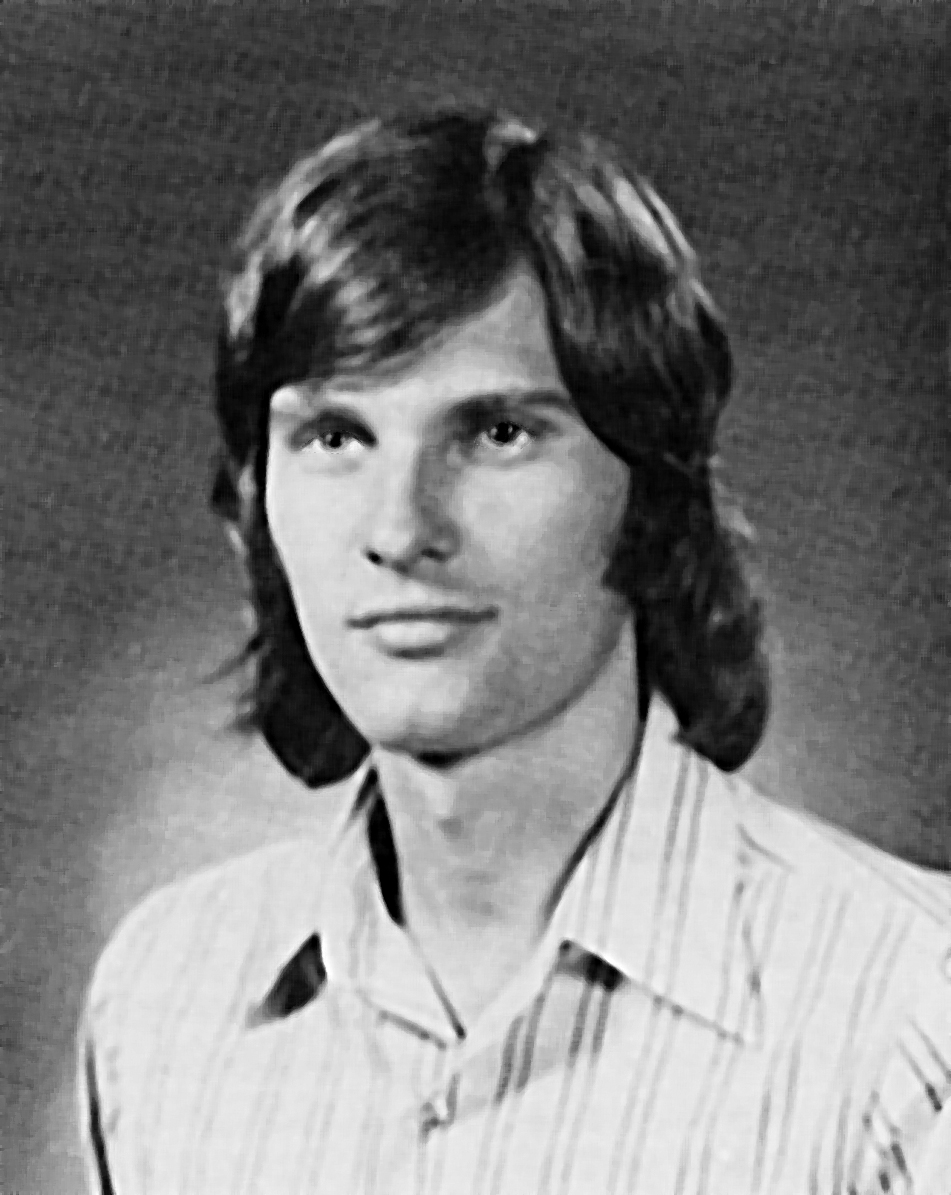

Kruk lasted a year in the ROTC program. “I walked in to drill after being on the Holy Cross Glee Club trip to Puerto Rico and I hadn’t cut my hair. Frankly, I think I was stoned, too. I was sent to be reprimanded.”

The officer Kruk met with said, “You’re an outstanding candidate, an Eagle Scout, but is this program working for you?”

“He was like the magic helper you find in fairy tales,” Kruk says. “You know, those people who come along who are there to provoke. This officer called my father, the lieutenant colonel, and said, ‘You’ve got a wonderful son here. He’s gonna survive; he’s going to do well, but not with the military.’”

•••••

Magic helpers come in many guises and Kruk encountered several at Holy Cross. To some he gives epithets, nicknames. There was the “creator of epiphanies,” bestselling author and English faculty member Marilyn French for whom Kruk once circulated a petition to get tenured. (She didn’t.) And then there was the Rev. Arthur Madden, S.J. — “Mad Dog” to his students — who proclaimed that the only permittable use of the passive voice was when referring to God Almighty, as in, “There is a God,” Kruk says.

Professor Virginia Raguin showed Kruk the interconnectedness of the art, history and literature of the Middle Ages, and when the young English major expressed interest in becoming a children’s book illustrator, Professor Helen Whall offered him space in her classroom to create a mural. The subject of the mural? “A huge tree showing different authors and aspects of writers. It was kind of overwhelming, almost a gaudy thing, I think, in retrospect,” Kruk says. “But she nurtured students that way."

Rev. Gregory Carlson, S.J., taught Greek and Latin literature at Holy Cross from 1974 to 1979. He, too, encouraged students’ creativity, assigning open-ended projects: poems, paintings, a scene from a play inspired by the course material, all were fair game. Fr. Carlson kept one of Kruk’s projects, a two-dimensional depiction of the final scene in the play “Medea,” for decades until, Fr. Carlson says, “Jonathan’s beautiful artwork yielded to the pressure of time and had to go the way of all flesh.

“It so typified Jonathan’s creativity, and his willingness to jump into things,” Fr. Carlson continues. “Holy Cross started me on a 49-year career in teaching and I have not had the pleasure of teaching another storyteller, someone with the gumption to put together a life based around entertaining people. What a deal!”

Fr. Carlson laughs in delight. “It is so encouraging to see someone I got to walk with for a while using his gifts so richly.”

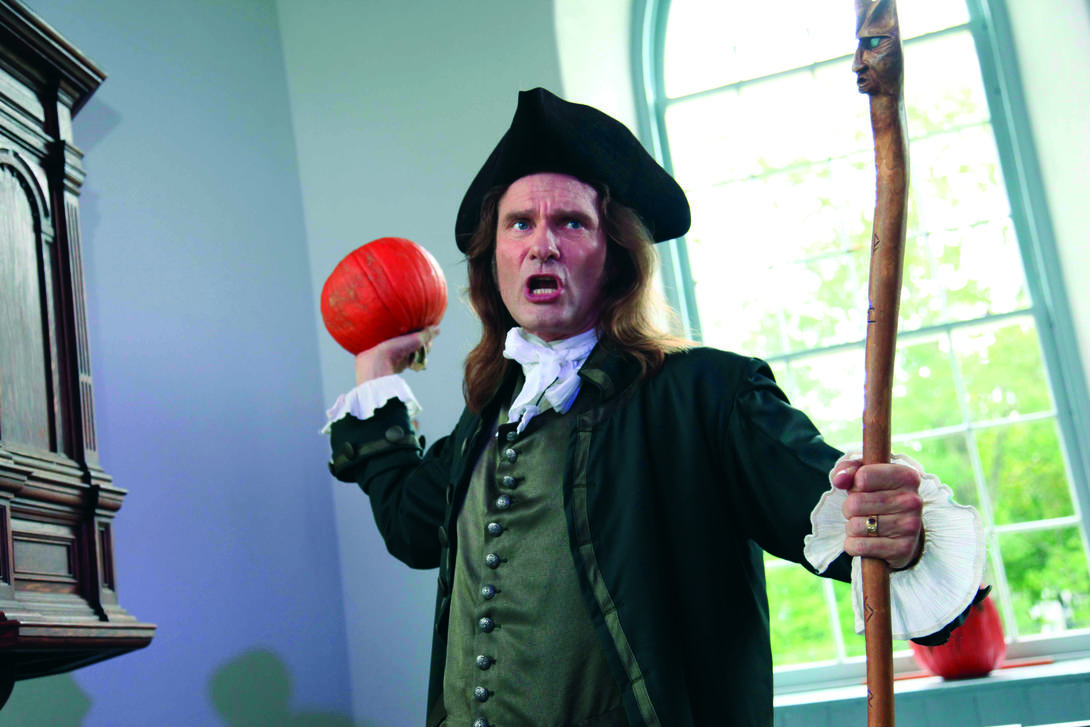

Kruk owes a debt to one other “magical helper,” a fellow student whose name he can no longer remember. He had been walking around Worcester on one of those gray, rainy, 40-degree days and ducked into a used bookstore. Kruk flipped through a collection of fairy tales illustrated by the 19th-century artist Kay Nielsen. “I came to a page with the illustration of a white bear with a forlorn-looking young woman perched upon its back,” he remembers.

It was a scene from “East of the Sun, West of the Moon,” a Norwegian folktale in which a girl goes on a quest to rescue a bear-by-day-human-by-night prince cursed by a witch. Kruk was entranced.

When he returned to campus, Kruk met a friend at one of the basement bars common to the dorms at the time: “She was tall, dark-haired, and I think she was on one of the athletic teams. I mentioned the fairy tale and not only was she aware of the story, but she knew the whole thing and, with a Narragansett beer in hand, she relayed the whole story. I was transfixed and knew I wanted to tell that story to kids.”

•••••

In fairy tales, three is the magic number. Three wishes. Three bowls of porridge. Three pigs, three bears, three Billy Goats Gruff. Oftentimes three enumerates the impossible: three tasks an often orphaned and usually poor young girl or boy must accomplish, such as scaling a giant beanstalk, spinning straw into gold or earning a living as an oral storyteller in the 21st century. That sort of thing.

Classmate William Correa ’77 was one of the first friends with whom Kruk shared his professional aspirations. “He said he wanted to be a storyteller; I said I wanted to go to Mars,” Correa says.

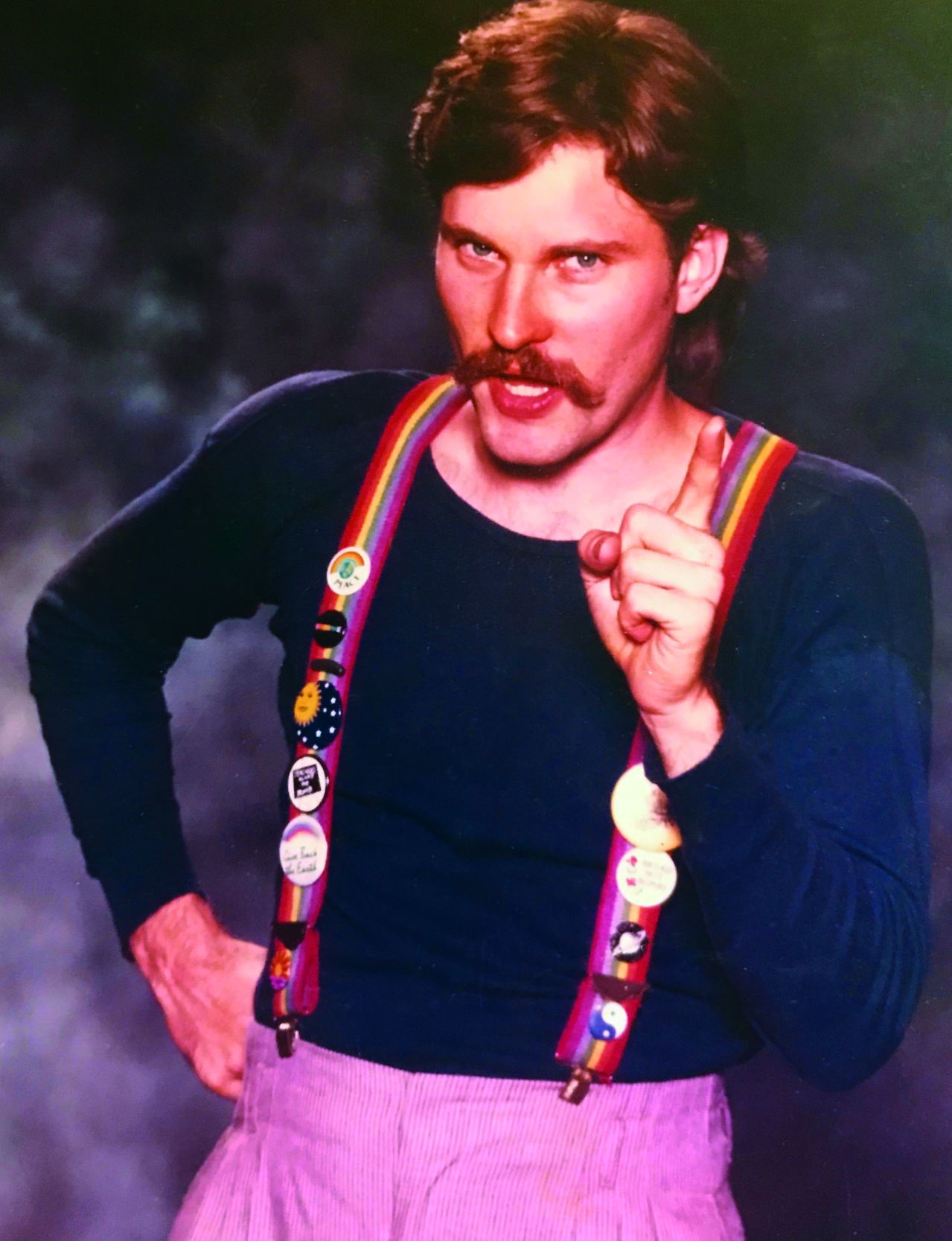

Correa and Kruk met in their junior year. They bonded over a fundamental counterculturalism and built a near-50-year friendship on mutual admiration. Correa’s sister encouraged Kruk to get a master’s in educational theater at NYU, which he earned in 1982.

In the years between graduation and full-time employment as a storyteller, Kruk worked as a traveling camp counselor, assisted Correa in renovating condos in Soho and watered office plants of the famous and infamous. Clients included ESPN, Fujitsu, Henry Kissinger and a member of La Cosa Nostra. Of Kissinger, Kruk says that the former national security advisor and secretary of state never spoke to Kruk directly. When he had concerns about office greenery, Kissinger would address them to his secretary, asking her to tell “the plant man” this or that. And so it went for a decade until a school superintendent heard a tape Kruk had made and hired him as a substitute teacher storyteller.

Listen as Kruk joins the Holy Cross Magazine podcast to talk about the mysteries behind Irving's classic, how stories can bring comfort, and much more.

“In ‘East of the Sun, West of the Moon,’ the heroine has to get the South, the North and the East Winds to carry her to the land east of the sun and west of the moon. By the same token, I had to be blown by these varied winds — as a construction worker, a plant man, a traveler cross-country — not knowing what I was going to do while all my college friends were getting corporate jobs or going to law or medical school.”

Kruk sighs, then smiles. “It took me a long time to become a professional storyteller,” he notes.

Correa has seen his friend perform many times over the years. “He can create this silence,” Correa says. “The kids get so much out of what he does. I look at them and see it’s life-changing. And the disruptive ones, the bullies and the troublemakers, they don’t have a chance. Jonathan just changes the dynamic, makes them part of the show.”