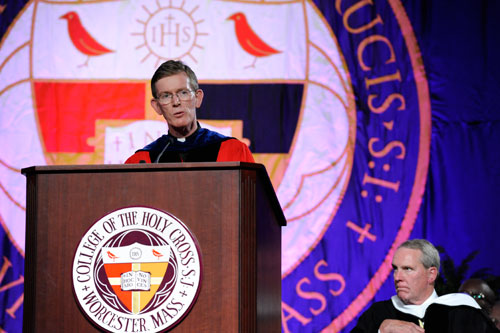

By Rev. Philip L. Boroughs, S.J., president

Honored guests, esteemed colleagues, beloved family and friends, brother Jesuits:

On this Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, when we celebrate the triumph of life-giving love, our extended College community gathers with government officials and Church dignitaries; academic representatives and Worcester neighbors; and many of my far-flung family and friends on picturesque Mt. St. James; where in medieval caps and gowns, with festive music and banners, academic procession and formal speeches, this assembly offers welcome and celebrates commitment as we look toward our institutional future. I am humbled and grateful for the affirmation of our Board of Trustees who have called to me to leadership, for the enthusiasm of our students and alumni who celebrate the transformative power of a Jesuit education, for the professionalism and commitment of our faculty on whom is built our institutional reputation, and for the kindness and generosity of our staff who sustain our quality of life.

Ultimately, I am here today because of the Society of Jesus, which initially educated me and then lovingly welcomed me into this apostolic brotherhood, and has formed and sustained me over the past 45 years. Building on the values and blessings of my family, my brother Jesuits have helped me to discern the meaning and purpose of my life and have given me a distinctive way of living and serving the world within a community captured by the spirituality of Ignatius of Loyola. This spirituality is poignantly incarnational, in that it finds signs of the presence of God in the created world, in human community and within the human heart. It is grounded in the divine invitation to enter into an intimate and liberating relationship with God in Jesus, blessed by the Spirit. This relationship progressively calls Jesuits and our colleagues to identify and surrender those perspectives, assumptions, and attachments which limit our imagination and freedom; and increasingly this relationship with the divine leads us to greater awareness of the beauty and possibilities of life and thought, the challenges and inequities of the world, and the importance of discerned service for justice and the common good. This grounding in the seen and unseen is why those of us who embrace this spiritual tradition are often referred to as “contemplatives in action,” men and women who treasure silence and listening, weighing and discerning, noticing the stirrings of mind and heart in the midst of the needs of the world, and then responding passionately and generously.

In Professor Robert Cording’s moving poem, “The Weeper,” which we have just heard, the final sentence about St. Ignatius is hauntingly powerful:

He wept, they say, because he’d suddenly feel

Entirely empty, and utterly grateful, all the doors

Of his heart, which was and was not his

At these moments, and which we know

Only as metaphor, swung wide open, able now

To receive and find room for all the world’s

Orphaned outpourings and astonishments.

It was Ignatius’ inner freedom to surrender himself completely to God and to detach from all those limiting self-understandings and compulsions which had earlier dominated his life, which allowed him to rest in radical emptiness and graced gratitude. In his emptiness, he could relinquish his concerns and preoccupations, he could stand before the power of the Transcendent, and he could open his mind and heart to receive what was being given. It was in fact this freedom to be empty before God which allowed him to see and hear and feel and taste what Professor Cording tenderly describes as the “the world’s orphaned outpourings and astonishments.” In these moments of contemplative attention his heart and mind were opened; he would marvel at the beauty and possibility of creation and, in gratitude, he longed to serve those whom his gracious God loved so much. In an increasingly complex and fragmented world seeking new self-understanding, Ignatius saw great need and suffering, but he also saw the hand of God at work in a world of new integrating possibilities.

For Ignatius, the signs of his times pointed to the rise of City States and new political alliances; to ongoing wars and violence in Europe, the Middle and Far East and northern Africa; to continents newly discovered, to widespread poverty and plague in cities where unprotected women, children and members of the Jewish community were routinely exploited and excluded, where trade and international exploration were opening up new worlds of language, culture and scientific discovery; where the Church was being divided by radical theological differences and in need of significant reform, and where education was becoming a means of social possibility not just for clerics and the powerful but for those of talent and imagination whatever their class. Into this world which was rapidly shedding its medieval worldview and embracing the Renaissance, a revived humanism questioned the rigidities of the past and opened up new ways of thinking and new worlds for discovery.

At the University of Paris, Ignatius of Loyola and his roommates, Francis Xavier and Peter Favre, shared the Spiritual Exercises and the desire to commit themselves totally to the service of God for the transformation of the world. They formed our religious brotherhood which firmly planted itself in the urban centers of the day. In the Society’s first few years, with a discerned commitment to the greater good but without a clear plan, these early Jesuits began what is now a 465 year educational tradition when they responded to the requests of the city fathers of Messina to open a school to educate their sons in ways similar to how the Jesuits trained their own. 50 years later, reflecting on a rapidly growing educational system, Jesuit theologian Diego Ledesma, posited 4 goals for Jesuit education which have endured over the centuries: to offer students skills for practical living; to contribute responsibly to their communities as citizens; to develop the mind and the ability to think, to reason and to celebrate the intellectual life; and to help individuals to achieve their ultimate end of union with God.

Almost 300 years after the founding of that first Jesuit school in Messina, Bishop Benedict Fenwick, and Jesuit Thomas Mulledy founded the College of the Holy Cross, named after the diocesan cathedral in Boston, to offer Catholic men in New England an educational experience that reflected the values Fr. Ledesma articulated. Matching the geography of our campus, the realization of their dream was an up-hill challenge. Unrelenting concerns over finances and admissions, the limited availability of Jesuits to teach and administer, the unsupportive social and political climate, rising religious intolerance, and a devastating fire which almost closed the college in its first decade were only some of the challenges they faced. In spite of these daunting difficulties, their fidelity to this struggling institution is a testament to their ultimate reliance on the sustaining power of God. Further, their belief in the liberating power of education and the intellectual life, their sense of mission to assist the predominantly immigrant Catholic population find its place in the social fabric of the United States, and their deep desire to educate the Catholic community in appropriating a more complete understanding of Faith, meaning and purpose propelled them forward.

Over the past 169 years of our existence, these same passions, in the Ignatian way, duly adapted to persons, places and times, have sustained Holy Cross through many other difficult moments: a turn-of-the-century national debate over the methods of the liberal arts curriculum which radically challenged and eventually refocused the fundamentals of humanist education in the tradition of the Ratio Studiorum; the economic effects of the Great Depression; a resizing of the student body and curriculum during and after the Second World War; the social, cultural and religious upheavals of the 60s and 70s which challenged our accustomed ways of proceeding, and consequently stimulated significant professionalization of academic standards, diversified our student body, welcomed co-education, appropriated the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, reformulated the role of athletics, and eventually moved us into national rankings. At each moment in our history, then, and with sometimes agonizing caution, deliberation, and prayer, Holy Cross has continued to cherish and appropriate what is unique to our Jesuit and Catholic heritage, has continued to raise the critical questions of meaning and purpose for our students, has increasingly emphasized the importance of the intellectual life, and has prepared our graduates for vocational and career choices which make a disproportionate difference in our world.

At this point in our institutional history, as once again we enter a period of change and transition, we are called to pause and assess where we are and what God and this moment in time are asking of us. While the campus has never looked as beautiful and welcoming, and our student body has never been as selective, and our faculty are renowned not only for their academic achievements but also for the quality of their engagement with our students, and our community-based learning and several shared enterprises have transformed our engagement with the city; and our campus liturgical life and retreat programs provide transformative opportunities for adult Faith, this moment of transition prompts a discerned reflection about who we are and how we will flourish in the future.We recognize that it is not only our internal transitions that cause us to reflect on our mission and institutional effectiveness, but the world around us is changing at an increasingly rapid pace and higher education is especially vulnerable to the uncertainties that are gathering.

For the past 4 years our world has been involved in a financial crisis second only to the Great Depression, and financing the ever rising costs of higher education is becoming increasingly impossible for the majority of American families. At a College which has proudly identified our commitment to need-blind admissions with our mission to be inclusive and diverse, we wonder how we can sustainably manage the need for skyrocketing financial aid while supporting our desire to be an inclusive community. The role of technology, often viewed as a potential cost-saver in higher education, as well as the provider of more targeted and nimble delivery of academic content, is forcing us all to think about what we need to know, how we deliver what we need to know, and how technology might enhance and not diminish the sacred relationship between faculty and student which makes a liberal arts education so transformative.

In each sector of the College community, as our respective areas of expertise continue to ask more of faculty and staff to meet ever-expanding professional standards, as communication technology has intensified exponentially the pace of our lives, and as pressure on our students not only to be well-rounded but also exceptional in multiple areas of achievement, we are all wondering if life can be sustained, if not balanced, between the competing expectations of professional life, family needs, civic and social responsibilities, and commitments to maintain our physical, psychological and spiritual well-being.

As a Jesuit institution where the number of Jesuits continues to diminish and colleagues are increasingly taking on the promotion of our institutional mission, we wonder what new roles and forms of engagement this appropriation will take. And as an American Catholic College in a season of political stridency and decreasing civility when the quality of religious freedom is being debated on many fronts; and within the Church itself, probing questions on the enduring significance of the Second Vatican Council, the implications of our call to social justice, and the uncertain relationship between role of law and its correlate, human compassion; we wonder what it means for us to be a private, Catholic Liberal Arts College in the Jesuit tradition. As our students, their parents and the public ponder the efficacy of a liberal arts education when considering its cost and the privilege it denotes, we ponder how best to communicate the enduring value of this educational experience.

This moment of intense challenge and turmoil, in many ways not all that different from those of the past, also offers us an opportunity to turn again to the virtues and practices which sustained this educational community over time. Whether or not we share a common religious tradition, our institutional history of remarkable leaders who lived as “contemplatives in action” offers each of us an opportunity to evaluate the quality of our individual and collective reflectivity which is essential not only for mature religious life, but in a parallel way all creative intellectual endeavors, as well as any sustained balance in our lives. Institutionally, our commitment to build a college contemplative center will offer us a dedicated place for prayer and reflectivity, as well as an opportunity for us to develop a variety of programs not only serving our students, but also our faculty, staff and alumni. The significance of this center and its programs may also stimulate us to begin a campus-based conversation on the rhythms of life that so many of us are finding dehumanizing; as well as to discern common expectations which prioritize our academic commitments of teaching, learning, and research and help us to integrate appropriately spiritual, artistic, athletic, and social co-curriculars, as well.

Our ability to engage thoughtfully the ongoing implications of a struggling global economy will require us to redirect aspects of our financial plan for the foreseeable future. How we listen, discern, and creatively act to sustain our academic excellence and retain our financial stability, and how we moderate our capital expectations in light of limited resources will be enhanced by our freedom to evaluate some of our traditional ways of proceeding and to imagine new ways of operating.

As a Jesuit enterprise, this moment of transition also invites us to continue to reflect on the global character of the educational experiences we offer on and off campus, and the make-up of our campus community. As demographic shifts in the US population move west and south, and as our world becomes increasingly interconnected, how might we attract and retain students, faculty and staff who will add increasing diversity to our campus identity? And as the Church and the Society of Jesus are promoting interreligious understanding as a necessary condition of global engagement, social justice and peace, and in light of recent violence and death in the Middle East, how might our educational experiences engage and advance our appreciation for diverse religious traditions and spiritualities?

With a national election upon us, we are reminded that discerning the contours of responsible citizenship requires not only sensitivity for the legitimate rights and needs of all those who live in this city and country, but as a nation blessed with a disproportionate percentage of global resources, we are asked to discern and embody our social responsibility for the human family.

Finally, as a community of educators, we have an opportunity to define in our time what contemplation in action means at Holy Cross. We can choose to be reflective, to live in the poet’s “graced emptiness” that heightens our sensitivities, frees our imaginations, and moves us toward generous and just living. We can choose to serve our institutional common good and our responsibilities to the world of need and possibility around us. In these challenging times we can choose to act with such integrity and ingenuity in making difficult decisions that others see in us ways of linking prayer, reflectivity and discerned choices that inspire and energize.

In his recent book, "College, What it Was, Is, and Should Be," Andrew Delbanco highlights an entry from an 1850’s diary written by a student at a small Methodist college. Delbanco writes:

One spring evening, after attending a sermon by the college president that left him troubled and apprehensive, he made the following entry in his journal: “Oh that the Lord would show me how to think and how to choose.” That sentence poised somewhere between a wish and a plea, sounds archaic today…..And yet, I have never encountered a better formulation…of what a college should strive to be: an aid to reflection, a place where young people take stock of their talents and passions and begin to sort out their lives in a way that is true to themselves and responsible to others.

For us at Holy Cross, this prayer first spoken long ago isn’t an archaic formulation, but a living one; one that is grounded in our Ignatian practice of being “contemplatives in action.” May this moment of new beginnings that we celebrate today, help us to listen, discern, choose and act to create a future with peace and hope.

Inauguration: Video of Presidential Address

Read Time

13 Minutes