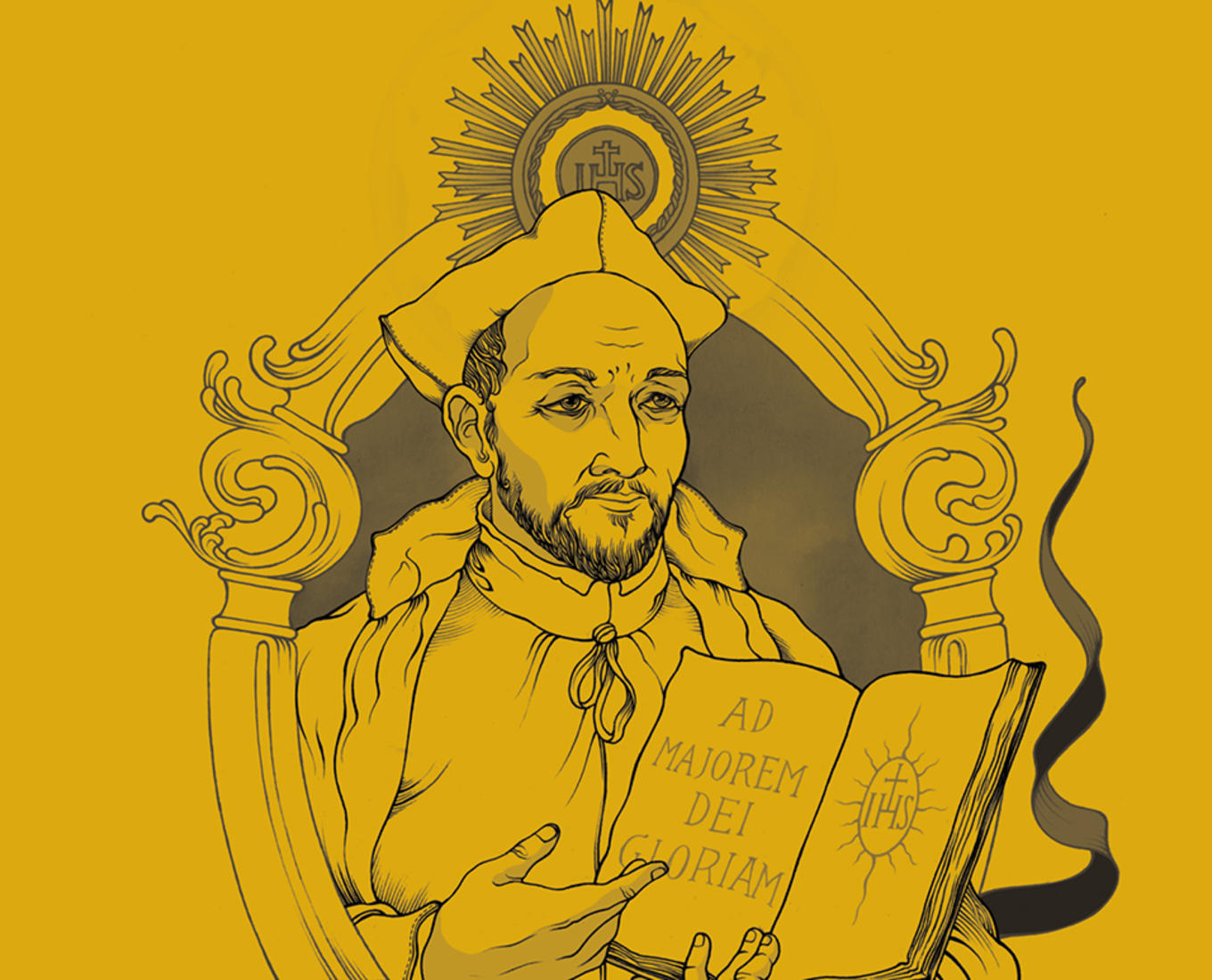

I’ve been asked to write a few words about the life and legacy of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Society of Jesus, whose members, among many other things, founded Holy Cross in 1843. But already there’s a problem in the one sentence I’ve written: His name wasn’t Ignatius, at least not originally: Instead, it was Iñigo, a name from the Basque country where he was born and raised. When his call to serve God and the events that followed from that led him into wider circles, like the universities of Salamanca and Paris, the name Iñigo sounded strange, so Ignatius it became. And that brings up the first of a couple of takeaways I’ll point out about Ignatius: His adaptability in the face of changing circumstances, or when dealing with different people. Like St. Paul, Ignatius was, or tried to be, “all things to all people.”

To those who were in his estimation spiritually weak, such as the Jesuit novices and scholastics — the seminarians — he could be kindly and indulgent. To those he judged to be strong, however, such as some of the companions who had been with him since the early days, he could be harsh, punishing or berating them for seeming trivialities.

On a larger scale, it’s remarkable to consider that Ignatius never intended to undertake the work with which the Jesuits are most identified: education. After all, few if any religious orders had operated schools as a significant ministry before his time. They trained their own members, but did not offer instruction to the children of the general public — this was another revolutionary aspect of the Jesuit enterprise. It was not until the Jesuits were invited to establish their first college in Messina, Sicily, in 1548, that Ignatius saw how this unthought-of undertaking would be part of what he called the magis — the greater good.

But this adaptability was not just Ignatius going with the prevailing wind. Instead, he was responding in every case with the loving generosity with which God had treated him. We might say it was adaptability, but always with the core conviction – core, as in “from the heart” – that we are all being invited to see the world as God sees it, with infinite love and compassion, and to respond in each circumstance with all the love and compassion we’re capable of.

Setbacks, dead ends and mistakes

After adaptability, the second takeaway is Ignatius’ quality of resilience. You don’t have to be a cynic to realize pretty quickly that adapting to new and changing circumstances is going to involve setbacks, dead ends and mistakes — and the life of Ignatius had plenty of these. He imagined himself at first as a grand courtier, in which case we never would have heard of him, but a battle wound ensured that this was not to be. After his first conversion, he was determined to spend his life in the Holy Land, literally in Jesus’ footsteps, but the Franciscans in charge of the holy places there thought they had enough problems without this oddball hanging around and they sent him packing.

In the face of every disappointment, every seeming wrong turn, one thing remained constant: He was always convinced that God was there with him and guiding him in ways that he, Ignatius, had not chosen. So strong was this conviction that he told a companion that if the project to which he had dedicated his life, the Society of Jesus, were to come to an end, that he would need just 15 minutes of prayer before picking himself up and getting on with the work of serving God. So a lesson for us: In the midst of setbacks, heartbreak and our own mistakes and bad choices, we can see with Ignatius that we are never abandoned, that we are still being led by God from what seems like disaster into something we cannot imagine. It’s OK to make mistakes, and here we might turn to a famous Jesuit alum, James Joyce, who reminds us that if we have the right disposition, “mistakes are the portals of discovery.”

The need for companions

Finally, the life of Ignatius emphasizes the importance of companionship. Though keenly aware of God’s abiding presence, Ignatius begins seemingly alone, whether convalescing in the sick room at home or preparing himself as a man of prayer in the cave of Manresa. But he soon draws other people to himself: First, those he directs in the Spiritual Exercises (in the beginning, laypeople like himself), then fellow students at the University of Paris, such as Francis Xavier and Peter Faber (who are portrayed conversing with Ignatius in the striking statue outside the Hogan Campus Center).

The original name of the Jesuits was the Company of Jesus — the companions — and we recall that a companion is literally one with whom you eat your bread. So the lesson here is a reminder to reach out to our friends and colleagues, to all the people in our lives, but beyond that, to make sure that we have at least one or two friends with whom we can share heart to heart what is most important, the things that, like bread, sustain us and give us life. And on the subject of companionship and the love that undergirds it, let me give St. Ignatius the last thought: “Love ought to show itself in deeds more than in words.”

Fr. Garavel serves as superior of the Jesuit community at Holy Cross.