This is a story about the stories we tell — to ourselves and to others — to create meaning in our lives. Taken together, those stories reveal what we value, what we hope to achieve and who we have become.

"That's what's so exciting and so important about the study of personal narratives: Through evaluation of our life stories, we might become better able to construct a life more deliberately and mindfully," says Jack Bauer '89, professor of psychology at the University of Dayton and an expert in the field of narrative psychology. His overarching hypothesis: "How people interpret and plan their lives predicts how their lives turn out."

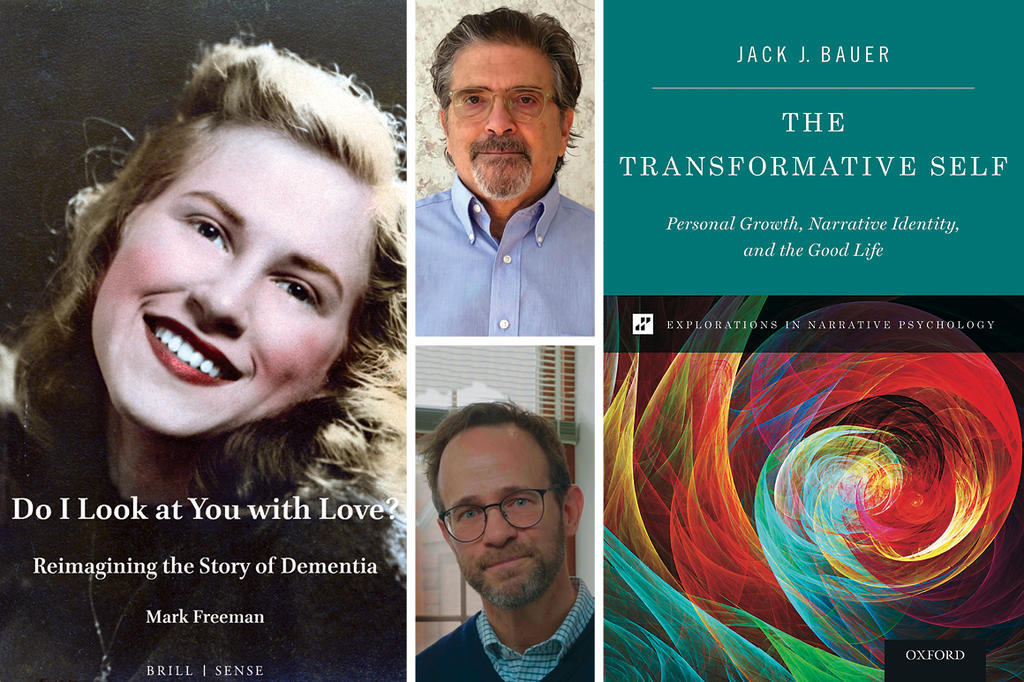

This spring, Bauer released his second book, "The Transformative Self: Personal Growth, Narrative Identity, and the Good Life," which was included in the Oxford University Press series, "Explorations in Narrative Psychology." The entire series was edited by Mark Freeman, Holy Cross Distinguished Professor of Ethics and Society and professor of psychology, who published a new book of his own this year, his sixth, "Do I Look at You with Love? Reimagining the Story of Dementia."

Despite their shared admiration, Holy Cross connection and research field, Freeman and Bauer took a bit of time to find one another professionally. Although Freeman was teaching at Holy Cross when Bauer, an economics major, was a student, Bauer didn't begin studying Freeman's work until a decade later in his postdoctoral fellowship in personality development at Northwestern University.

"Both Mark and I are very interested in the development of personal identity and exploring the ways that people create meaning through the stories they tell," Bauer says.

The Role of Reflection

When mentally building these stories of ourselves and our relationship to others, Freeman and Bauer agree that the ability to reflect is key. "We're all interested in planning for a future that's good; we set goals to make our lives better or to perpetuate things that we value," Bauer says. What's important is to understand that our thoughts are interpretations of things we have experienced, he adds. When we understand this, we can begin to look at what motivates our behavior. "If we notice the way we have been motivated by a particular value in the past — in our work, in a relationship — we can understand ourselves better and react accordingly in the future."

In this, reflection in the form of hindsight can be particularly valuable, Freeman notes. "An experience has a particular meaning in the moment, but over time, that meaning can change," he explains. In the moral realm especially, people often act first and think later, and it is only after they gain some distance on the situation that they can view it in a new light. Freeman refers to this phenomenon as "moral lateness." For example, in the heat of the moment you can be convinced of the rightness of your point of view only to realize later that there's another way of seeing things. "Looking back on what we couldn't — or wouldn't — see before can allow for growth. Through memory and our stories, we can take stock of things and perhaps correct the errors of our ways," he says.

Bauer's research shows that the way humans construct their stories is also revelatory. When we tell stories of our lives to ourselves and others, we may choose to tell a particular tale, but the way we tell it is far less conscious, he says: "When telling personal stories, we use narrative tones, underlying themes and scripts that we borrow from cultural master narratives, and we do all these things mostly unconsciously."

One such cultural master narrative is that of personal growth, Bauer explains in his book. "In literature we see this master narrative in the bildungsroman genre — the genre of character development," which is recognizable to persons ages 8 to 80. Though separated by centuries and cultures, "The Odyssey" and the Harry Potter series satisfy for being familiar, even predictable, yet inspiring: The protagonist takes a journey of their own choosing, encounters teachers, develops new skills, endures trials and emerges as the hero. Stories like these become bestsellers for a reason, Bauer says. "We like them because they showcase our culture's ideal of personal growth toward a good life, so we try to apply these stories to our own lives and the lives of those around us. We can make sense of others' lives because we share certain narratives, even though we're not always aware of it."