This commentary appeared in The Boston Globe on May 29, 2023.

During the height of the civil rights movement, at a time when racial integration was sparking controversy on many campuses, College of the Holy Cross President the Rev. John Brooks drove around the country to personally recruit Black high school students to the college’s all-male, primarily white campus in Worcester. The 20 young men he recruited have become an illustrious group, including business leaders, a Pulitzer Prize winner, a Super Bowl champion, and Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, class of 1971.

Thomas, once the beneficiary of the most overt example of race-based admissions I can imagine, will probably be among the Supreme Court’s majority in the next few weeks when it is expected to strike down the use of affirmative action in college admissions.

In his 2007 memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son,” Thomas argued that Black people are actually the victims of race-conscious admissions, as it stigmatizes their achievements. He believes students of color should be able to prove their capabilities without the cloud of racial preference.

Thomas’s lived experience has led him to his own understanding of affirmative action. However, as a scholar of race and the law, as the first Black president of his alma mater, and as the son of civil rights activists, my experience has offered me a different perspective, one that I think is shared by a significant portion of Black people in this country.

Thomas is six years younger than my father, Weldon Rougeau, who was a student leader during the civil rights movement. My father walked into a Baton Rouge, La., department store in 1961 holding a sign demanding integrated lunch counters and more Black workers. His protest got him arrested and jailed for three weeks. A second arrest for distributing “don’t buy” leaflets landed him in solitary confinement for 58 days and led to his expulsion from the university he attended.

He and many others went to jail in part to provide opportunities for those who would follow them, people like Clarence Thomas and me. My father and most of his peers were, and remain, strong proponents of affirmative action in some form because they know their work remains unfinished.

As a nation, we often act as if the present were disconnected from the past. To be American is to be liberated from what came before, and we’ve been led to believe that, if we have better grades, wake up a bit earlier, and save a bit more, wealth and success will come to us by right. But we know this is not always true. Our country doesn’t work that way for most, and it never has.

Opponents of affirmative action rest their opposition in part on the notion that Black Americans have now been fully liberated from the nation’s racist history. Indeed, governors and state legislators around the nation are working feverishly to ensure that public schools don’t teach young people stories like my father’s, lest they begin to question whether the past might be relevant today and come to the conclusion that working harder is not always enough.

Most studies agree that the consequences of the complete elimination of affirmative action in higher education admissions will be a significant decline in the presence of Black students at selective colleges and universities, as has been the case in the states that have banned the practice. Can we honestly argue that hundreds of years of slavery and racism have nothing at all to do with it?

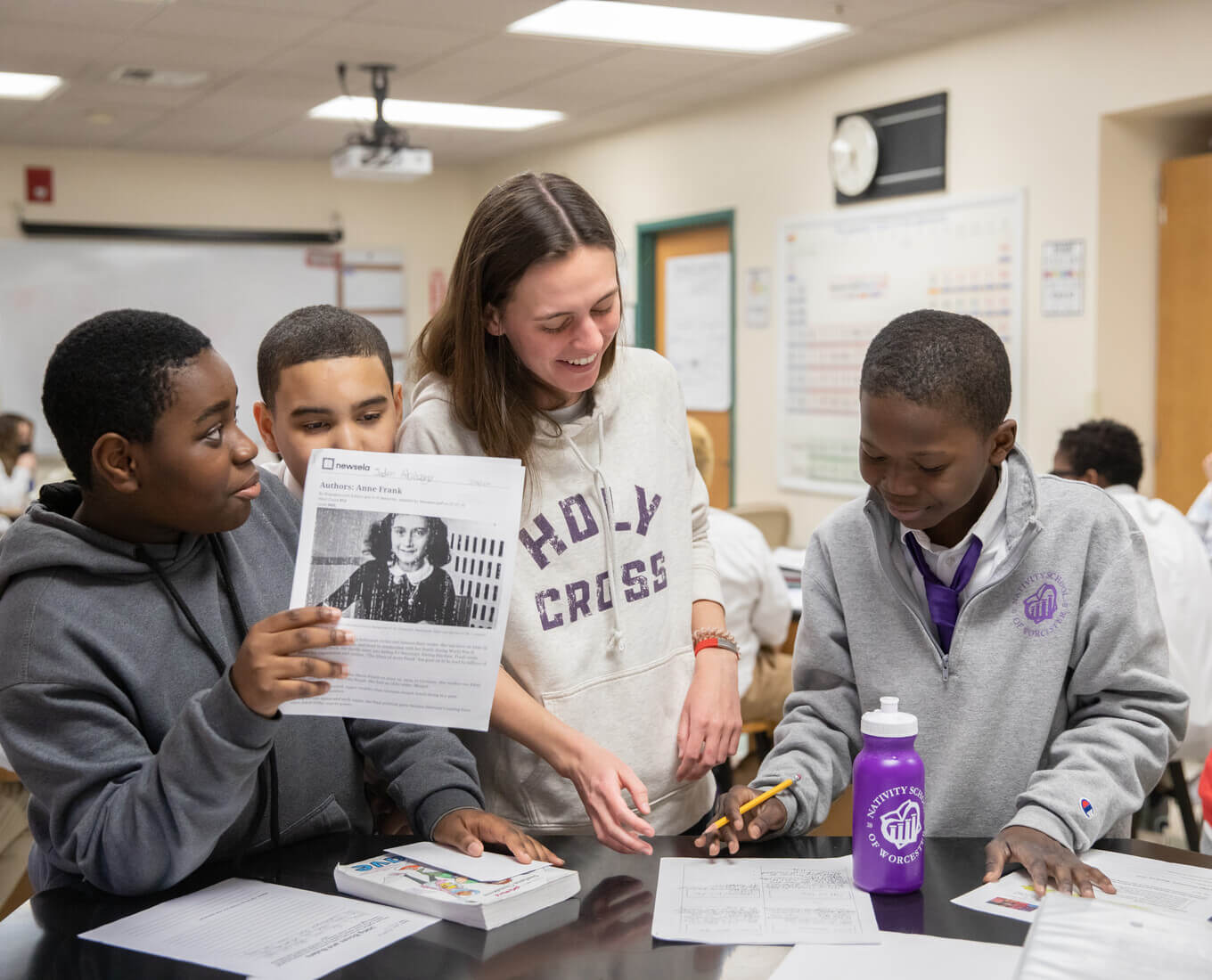

At Holy Cross, we continue to believe, as Brooks did, that a diverse learning community is essential to our academic and Jesuit, Catholic missions. It creates a rich learning environment that promotes understanding of and empathy toward people of different backgrounds. It forces all of us to engage directly with uncomfortable realities about our nation’s past and to consider the consequences of ignoring them.

Many higher education institutions across the country are already taking steps to prepare for what’s to come, from reducing barriers to admission to intentionally recruiting applicants at high schools in underrepresented communities, and developing partnerships with organizations such as QuestBridge and American Talent Initiative, which work to help expand opportunities for marginalized students.

Although my father’s courage helped to open doors for me and others, his sacrifice came at a cost to him. His story is an American story, and it deserves not only to be told but to be considered in the context of what it means for us today. Thurgood Marshall once said, “Unless our children begin to learn together, there is little hope that our people will ever learn to live together.” We owe it to the next generations, and to the ideal of equal opportunity in this country, to continue to try.

Vincent D. Rougeau is the president of the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester. He previously served as dean of the Boston College Law School and the inaugural director of the new Boston College Forum on Racial Justice in America.