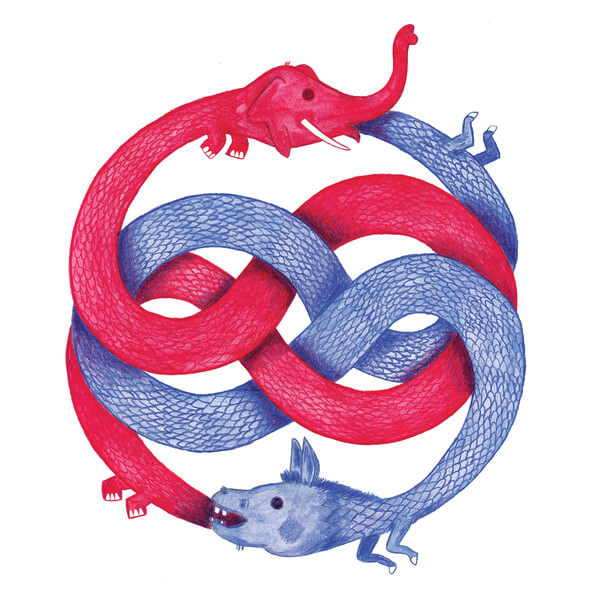

What is likely to be our fate as a divided democracy on fire with volcanically hostile political rhetoric and deadly attacks on one another? What should we try to do to save our nation and ourselves? What if we fail to tamp down the ferocity of our divisions, to prevent the shattering personal and economic losses that we can impose on each other? What if we fail to avoid generating the weaknesses in our national power that divisions create, exposing us to dangerous aggressions from international enemies near and far?

Despite what we might have grown up assuming based on celebratory accounts of our nation’s political birth and growth, the past dramatically reveals how extremely hard it is to create democracies in the first place. Over time they usually experience grave challenges to their continued existence. Perhaps most frightening of all, history shows that even after long periods of success, democracies can come crashing down. Often they end with horrifying casualties for their constituents, especially when virulent divisions expressed in words of contempt for each other become the order of the day.

“Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me!” must be the phoniest adage ever expressed. Just think of the devastating psychological and social effects increasingly produced by bullying and demeaning social media. The havoc and terror that can be inflicted by “sticks and stones” — today, think “bullets and bombs”— are of course horribly real and becoming more and more likely from many directions. Still, more often than not, it is words — online, in print, in person — that provide the initial provocation to blazing anger, physical violence and even murder.

Since democracies have traditionally and appropriately prized “free speech,” words that can be as sharp and damaging as physical weapons have long been a feature of democratic societies. A consequence of this necessary democratic freedom is, unfortunately, that words spoken with little regard for their effects on others can become verbal fireworks. These words inflame divisions in democracies through personal attacks on individuals and groups.

Words have this political impact because they can be so effective at undermining and destroying people’s sense of belonging to a community of citizens. A Google search done recently for the phrase “sense of belonging” yielded about 399,000,000 results — a clear index of the contemporary prominence of this social phenomenon.

The past also reveals that no democracy can survive in the long run without a recognized sense of belonging among its citizens. This does not mean that citizens have to all like each other, or agree about domestic and international policy decisions, or only say nice things about one another. But it does mean that incessantly and insultingly denigrating the competence and sincerity of one’s political opponents is a strategy for mutual self-destruction in a democratic society, even a highly successful one.

The fate of ancient Athens — the most successful early democracy — in its colossal descent from power and glory provides a disturbing proof of these claims. The story of its political leader named Phocion sums up this awful history. Over a long career lasting into his 80s, he was elected to Athens’ highest political office (held for one year at a time) more often than anyone else ever — 45 times!

Athenian voters valued Phocion’s successful leadership in military actions against hostile foreign forces. They recognized his incorruptible commitment to promoting policies that in his view would keep Athens safe inside and outside. But in the end, a majority of Athens’ citizens raucously disregarded standard legal procedures to condemn him to death. This was a punishment for his failed judgment in dealing with the enemies who defeated the Athenians and stripped away their democracy.

The citizens’ anger against their formerly celebrated leader was fueled by Phocion’s lifelong habit of publicly expressing only strident criticism of other citizens. He became infamous for giving good political advice in the form of brilliantly and brutally insulting comments. He never took a bribe to change his policy recommendations, but he also never said a word that supported a sense of belonging among the citizens of the democracy he so deeply valued. He dismally failed to understand democracy as a social phenomenon. In the end, he died as a contributor to the fatal division, not the salvation of Athens’ famed democracy.