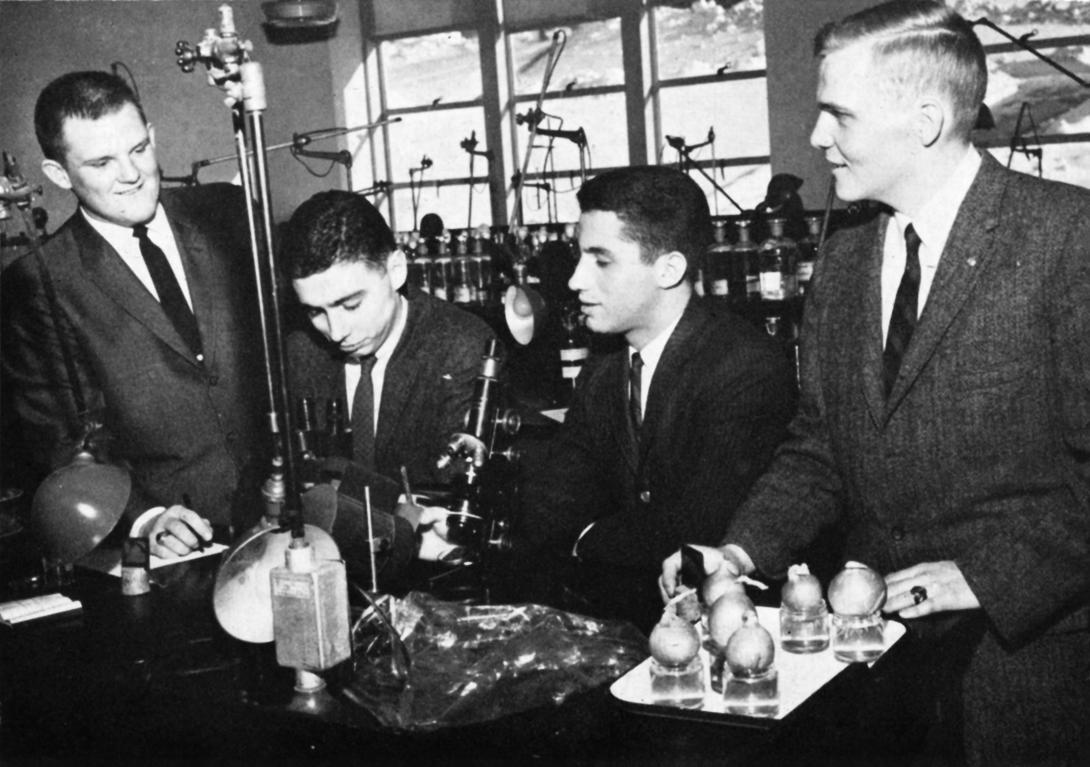

Later, at Holy Cross, the two men would enroll in the A.B. Greek premed program run by the formidable Rev. Joseph F. Busam, S.J., chairman of the premedical and predental programs.

“Fr. Busam basically told you whether you were going to go to medical school or not,” Card recalls. “And there were those of us to whom he said, ‘Well, I don’t know.’ Fr. Busam had, over the decades, established a very positive reputation with the medical school admissions committees. And he was definitely pretty good at picking out who would do well where.

“And, so, he would say, ‘OK, well, these are your choices’ and you could be pretty sure you would get in if you applied to one of the places that he thought you should apply to.”

Fauci smiles at the mention of his major and Fr. Busam.

“I still can’t explain to people today what A.B. comma Greek comma premed meant,” he says with a grin. But the program served all of Fauci’s intellectual interests. “We took just enough science to get into medical school. You know, we had Fr. Busam for biology, chemistry and physics, but we also took a lot of philosophy courses. And the humanities are such an important part of me as a physician-scientist and public health figure.

“That was the reason I went into medicine because fundamentally as a person growing up being influenced greatly by the Jesuit tradition, I was more interested in the humanities and human nature than I was in human physiology, but at Regis I found I also really liked science — and I was good at it,” Fauci says. “So, I said to myself, what could it be to combine the humanities with science and medicine, and [the A.B. Greek premed program] was absolutely a natural marriage of the two because you really got a feel for the nature of evolving civilizations and how they related to each other and what mankind is and is not.

“And that triggered my intense interest in global health,” he continues. “And with that comes an understanding of the disparities in the world, which I’m very sensitive to. That you still now, in 2020, have a couple of hundred thousand babies in Africa dying each year from malaria or tuberculosis or HIV, or the fact that there’s racial and ethnic health disparities ...” He pauses. “All of these things are totally big flags on my radar screen that, if I wasn’t deeply entrenched in the humanities, I might be a little bit cold to and not fully appreciate how important it was to address those things.

“I’m sure that people who did nothing but physics and chemistry do feel the same way I do. I don’t think I have a lock on that,” he continues. “But, for me, that my training in the humanities made me much more receptive to all of these things in society is integrally related to my role as a physician, a scientist and a public health official.”

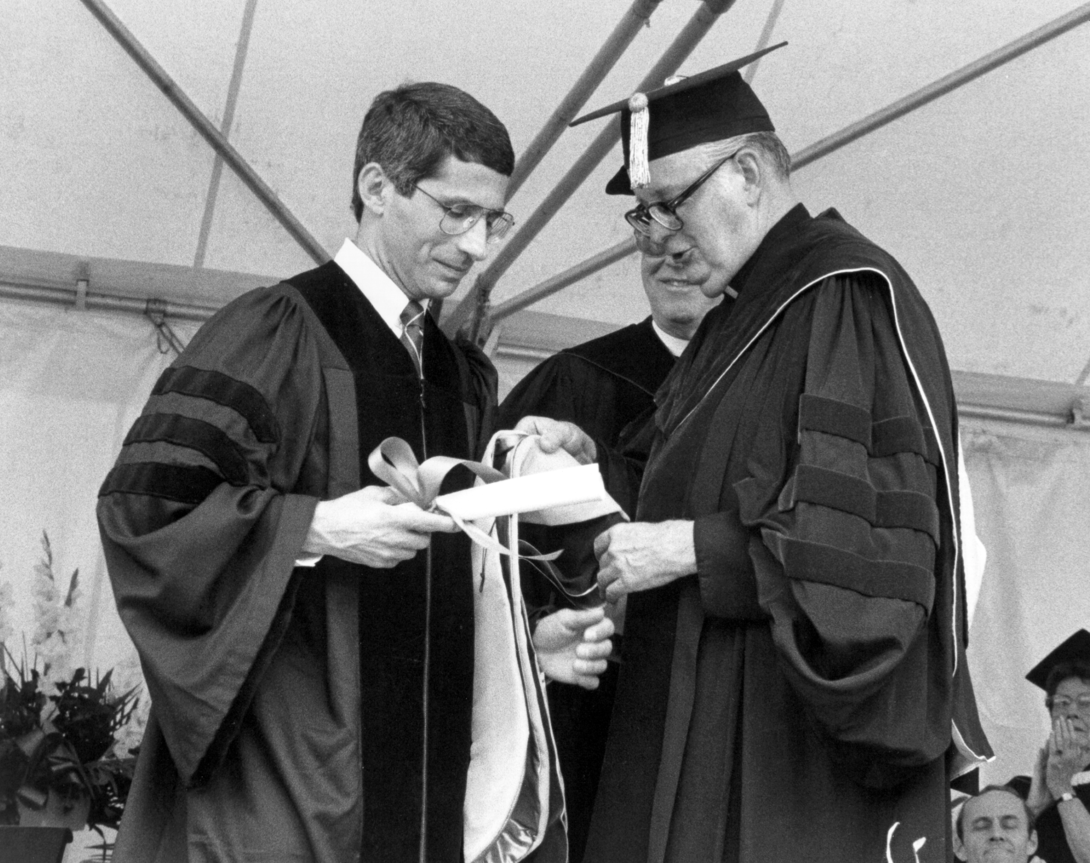

Peter Deckers, M.D., ’62 says much of what the public admires in Fauci was apparent from youth: “He came from a family where the work ethic was over the top and the commitment to excellence was as strong as it could be. He brought those gifts to Holy Cross with him. Some of the students could get very tense and uptight when they came under the kind of pressure that existed at Holy Cross, but Tony thrived on it. And you’re witnessing that today when you watch him dealing with the government and the public.

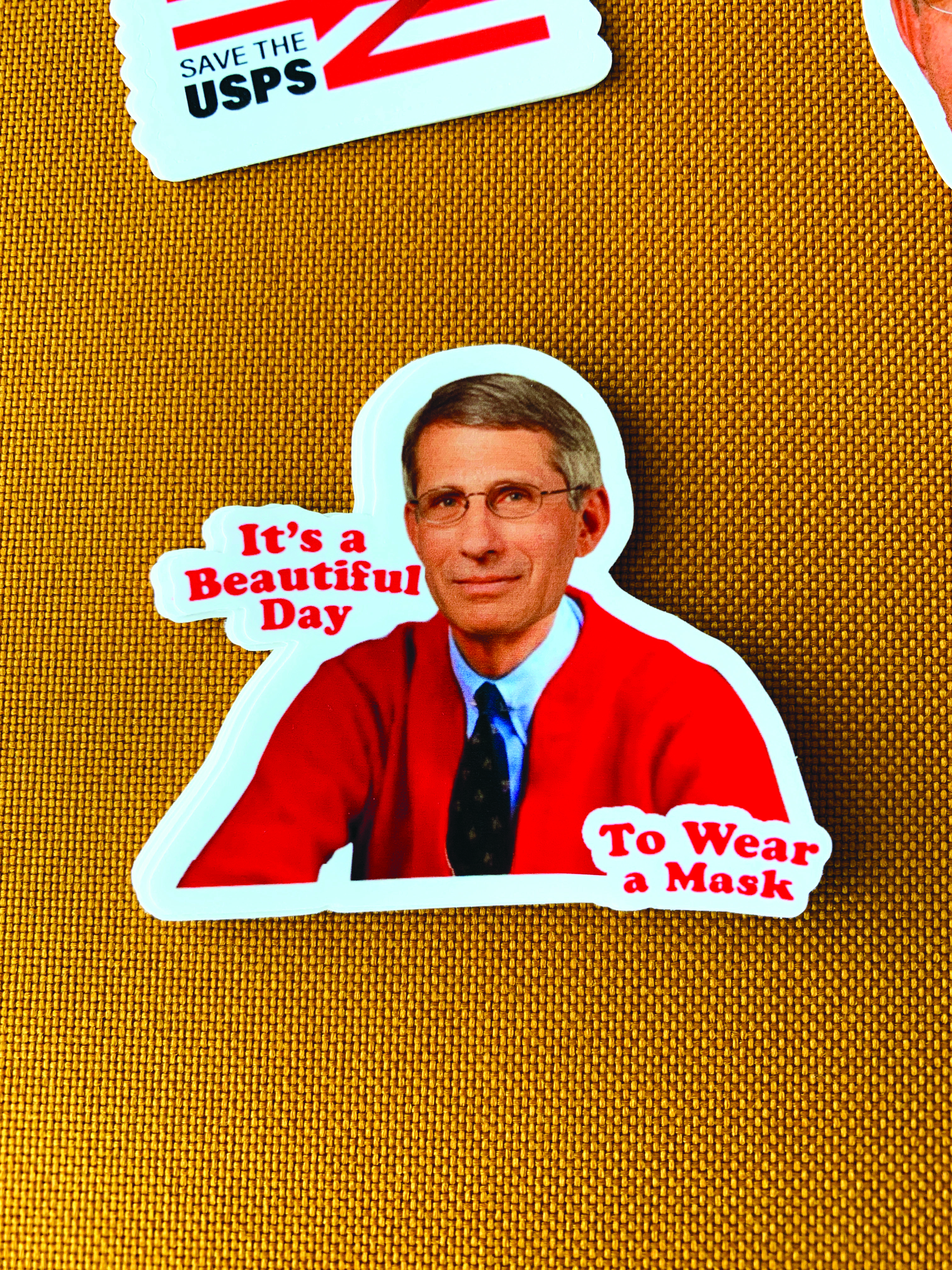

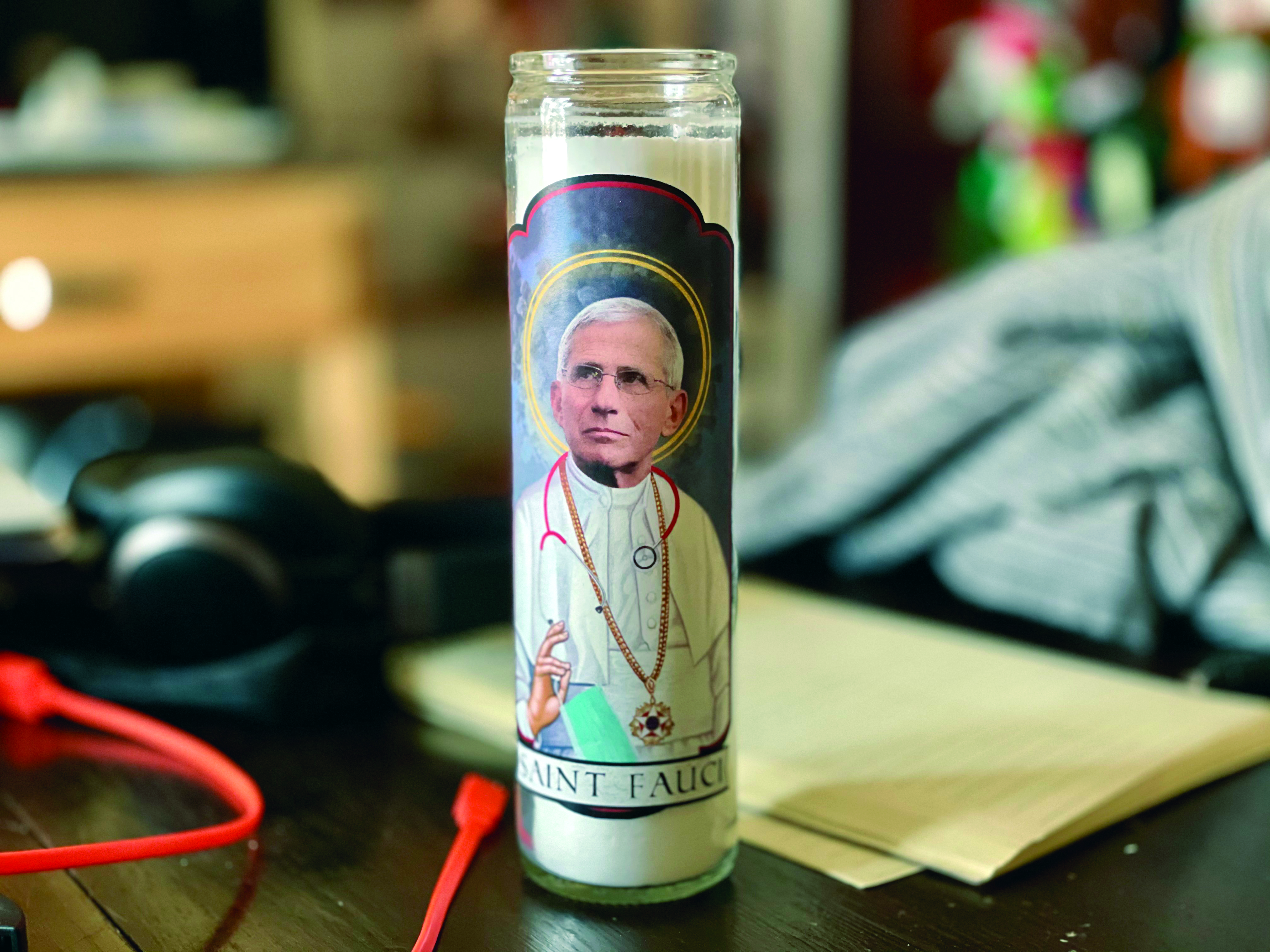

“He’s become known as America’s doctor because he’s handled himself with such eloquent elegance and equanimity,” Deckers adds. “He has an evenness of soul and spirit. He doesn’t argue from emotion. He argues from science.”

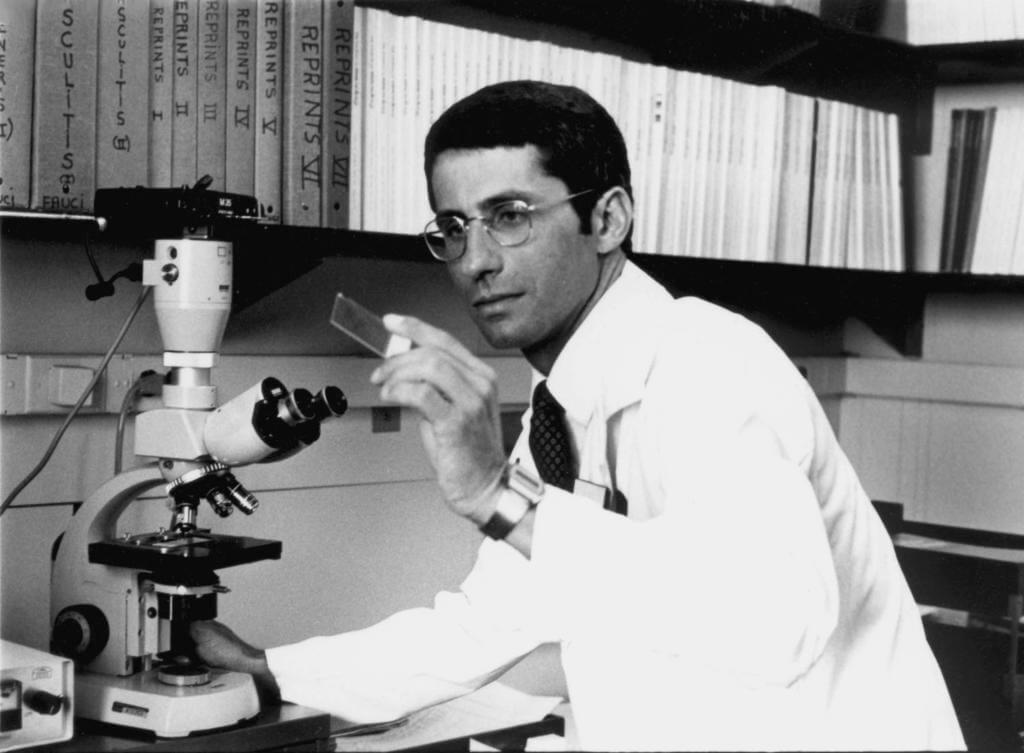

Fauci is one of the 40 most-cited living researchers in peer-reviewed journals in the history of medicine, and he also knows how to make his meaning clear to a broad spectrum of people, says classmate Jim Mulvihill, D.M.D., ’62. “He’s one of the best, if not the best, people you’ll ever hear explain science — whether to a senator or to the average layman — what’s going on with whatever, with HIV, with COVID, whatever.”

Fauci, Card, Stanley and Mulvihill waited tables together at Kimball Dining Hall, for which they were paid $2 a meal; they took pride in defraying the cost of tuition for their parents. Serving their classmates in this way offered a different education: You learned to be organized, efficient and quick. “There was a camaraderie there,” Card recalls. “Each of us had three tables we were responsible for and we would get these platters of meat, vegetables and potatoes on these large 3-foot oval, aluminum trays and put them up waiter-style on the flats of our hands and bring them to the assigned tables.”

Mornings were hectic, Mulvihill recalls: “I’d get there by quarter of seven in the morning and have 45 minutes before the thundering herd arrived. I’d set up my tables, grab a couple of those great pastries that came right out of the oven and also do a little bit of studying.”

For Fauci, his combined experience of delivering prescriptions, waiting tables and working construction summers during college offered insights into what mattered to regular folks: health, welfare and employment. “I really got a good taste of what the hardworking man or woman has to do, like the people who are outside my window right now, you know, doing landscaping or fixing potholes,” he says. “I’ve done that. I understand them.

“And now that I’m in a somewhat privileged position, I have an intense empathy for people.”

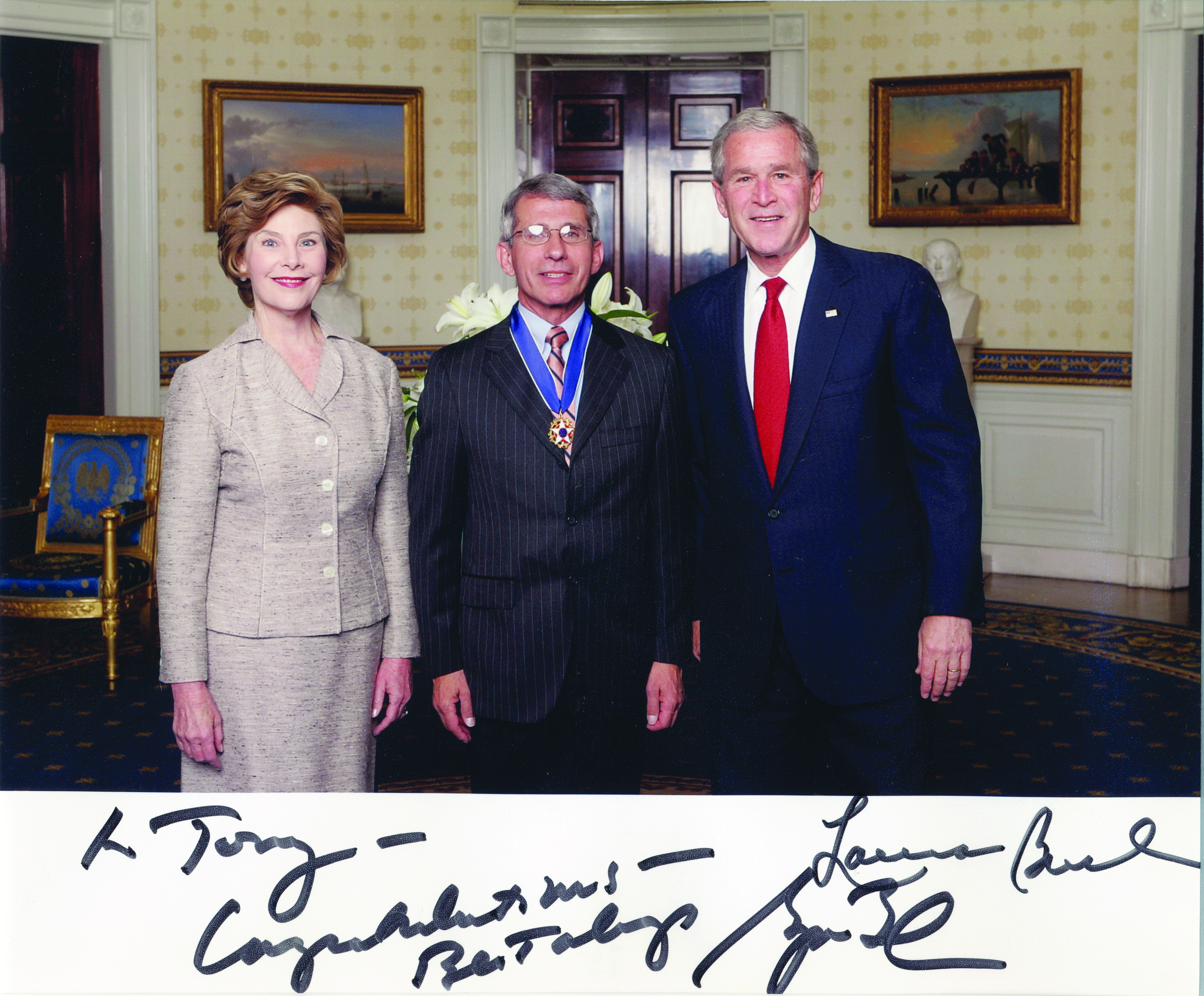

On occasion, that empathy has prompted Fauci to refuse offers of career advancement from men unused to hearing “no” for an answer. Mulvihill recalls trying to call his friend one evening and getting a busy signal for hours. “When I got through, I asked Tony what was happening and he said, ‘It took me a long time to persuade President Bush that I shouldn’t lead the whole NIH.’

“I believe Tony had opportunities to head the NIH from at least three presidents,” Mulvihill continues. “But Tony was doggedly after HIV at the time and he said, ‘I want to stay here and try to solve this problem.’”