Throughout his career in law and higher education, Vincent D. "Vince" Rougeau has worked across the United States and abroad, yet regardless of where he is or what his title may be, the theme has been the same: working to promote human rights, human dignity and a community that fosters both.

From a Catholic family with deep roots in Louisiana, including parents who walked the walk during the Civil Rights Movement, to the high poverty boroughs of East London, where he teamed law students with residents to solve problems together, Rougeau has focused on building communities that concentrate on a clear instruction found throughout the Old and New Testaments: Be a people who look out and care for the poor, the marginalized and the defenseless. Balancing basic human rights and dignity with a community's responsibility to promote such is at the heart of a doctrine known as Catholic social teaching, a tradition Rougeau has spent his career studying, putting into practice and teaching to generations of law students.

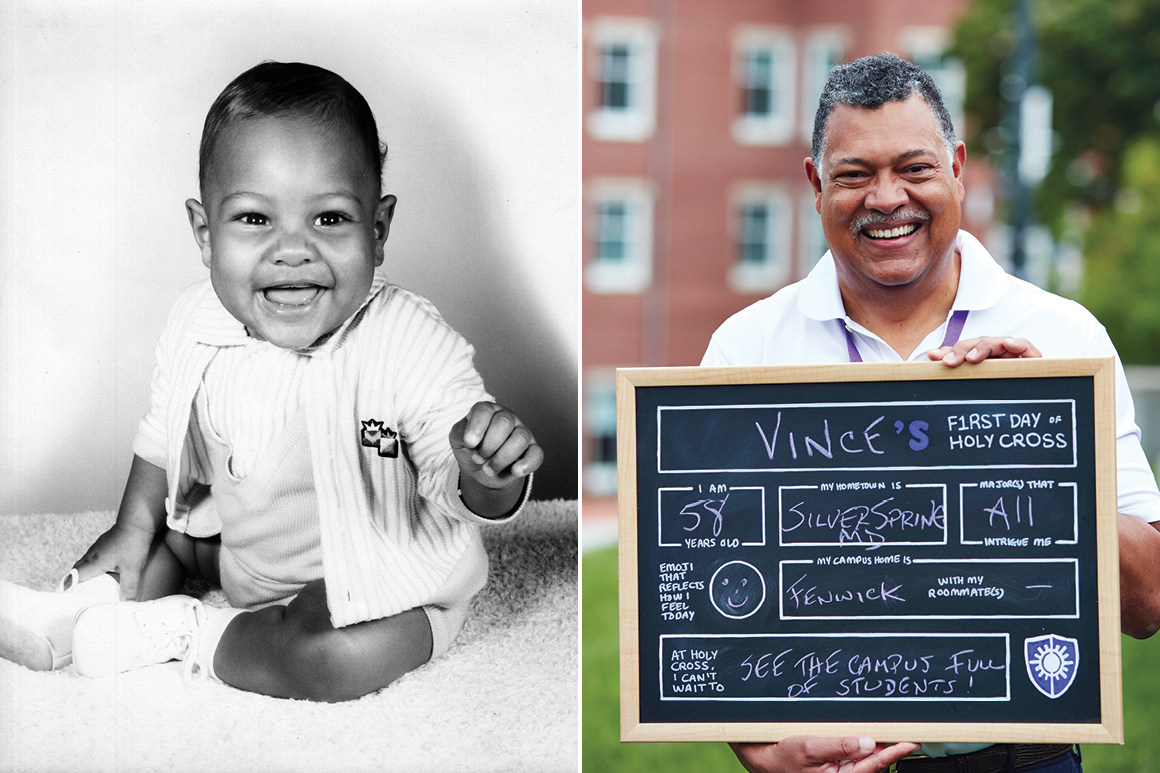

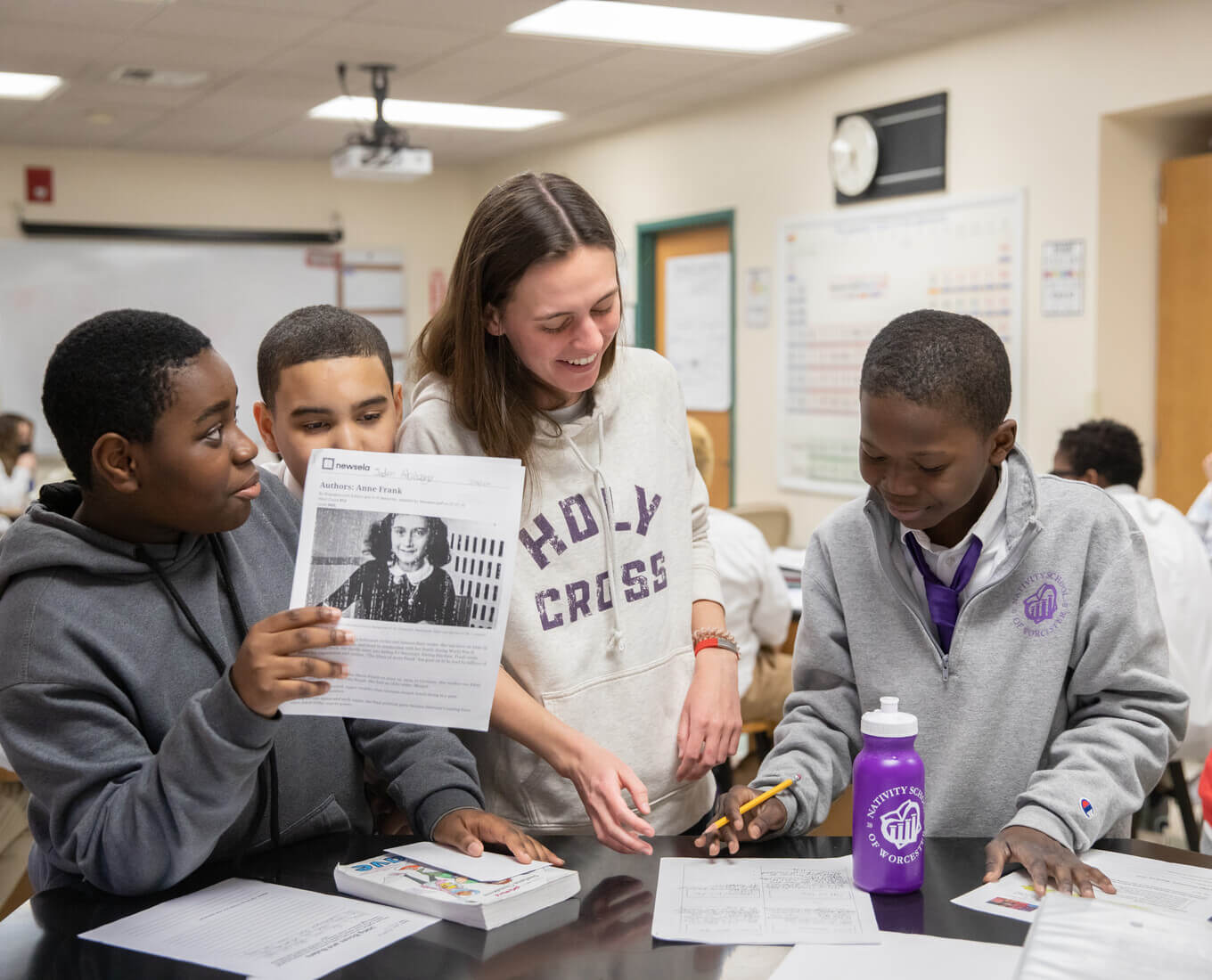

This fall, Rougeau finds himself in a new city and a new role as he prepares for his October inauguration as the 33rd president of the College of the Holy Cross. He will be the Jesuit institution's first lay leader in its 178-year history, yet in examining Rougeau's career and scholarship and hearing from his family and colleagues, one thing is clear: His lifelong mission dovetails perfectly with the charism of the Society of Jesus.

A Family of Faith

Rougeau's roots in southwest Louisiana stretch back eight generations, including his grandparents, who founded a Catholic parish for the Black community in the city of Lake Charles.

"We come from a long line of Catholic families," says Weldon Rougeau, Vincent's father. "Vince was always very good about getting involved in the church."

His mother, Shirley Small-Rougeau, adds that in addition to being a cantor, her son was a lector at Mass, a capacity in which he still serves today. "The basis of most African American lives, since I've been around, has been their faith, and we took faith very seriously," Small-Rougeau says. "Most Catholic people go through their First Communion and Confirmation and then it's over, 'I'm done with CCD,' but Vince went through the entire period up until he graduated from high school."

Rougeau recalls that, at the time, he didn't quite realize that the basis for his lifelong commitment to and study of Catholic social teaching was planted in those early years of parish life.

"My grandparents need to get a lot of the credit for being the rocks of our understanding of who we were as a family of faith, what our traditions were and where they came from, and how they were to be maintained," Rougeau says. "They were deeply spiritual, deeply faithful people, very modest and simple in their desires, but wealthy in their love of neighbor and community and their desire to live out their faith in a way that emphasizes the things that are important: family, communities, caring for the poor and those in need. With that kind of foundation, the older I got, I started to realize these things that are important to my family, social justice and civil rights, have a lot to do with our faith."

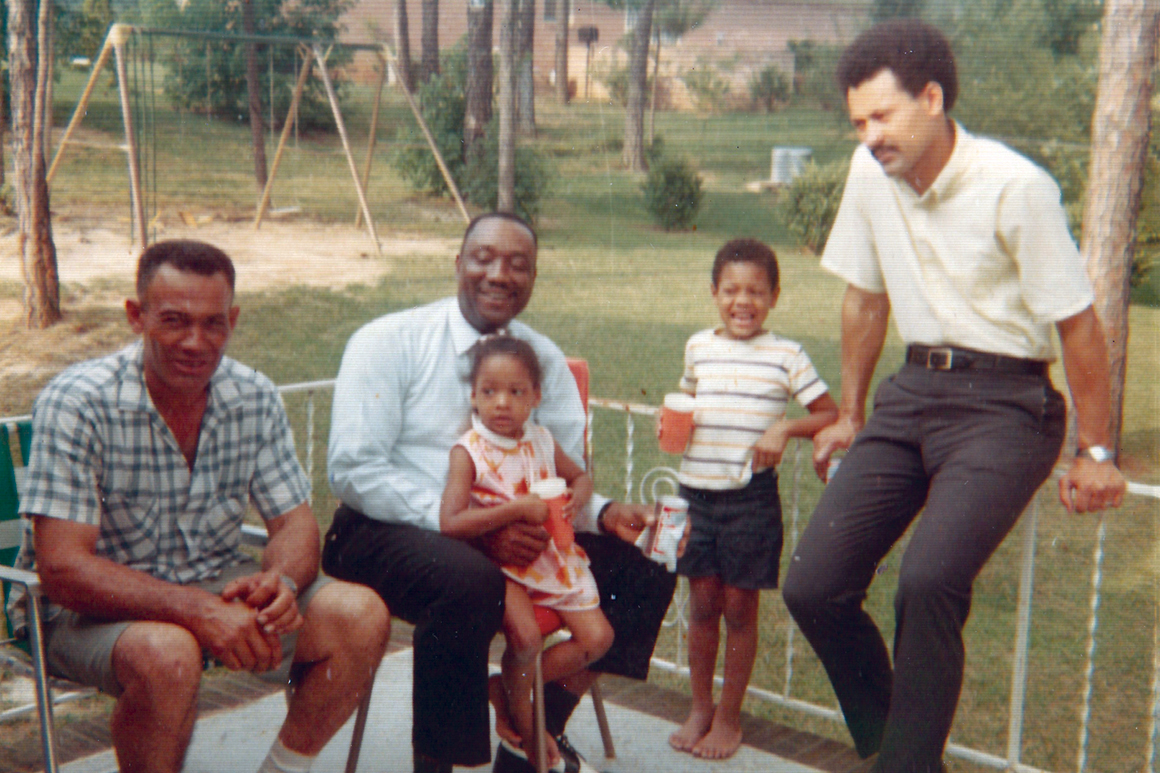

Rougeau is the oldest of three siblings, with a younger sister, Dominique ("Niki"), and younger brother, John, and their parents were active in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

"As they grew, we explained to them and educated them on the injustices that existed in society," Small-Rougeau says. "So our participation in marches, sit-ins, protests, all those things, was something they understood the purpose of and we always involved them in whatever we were doing when they became a little older."

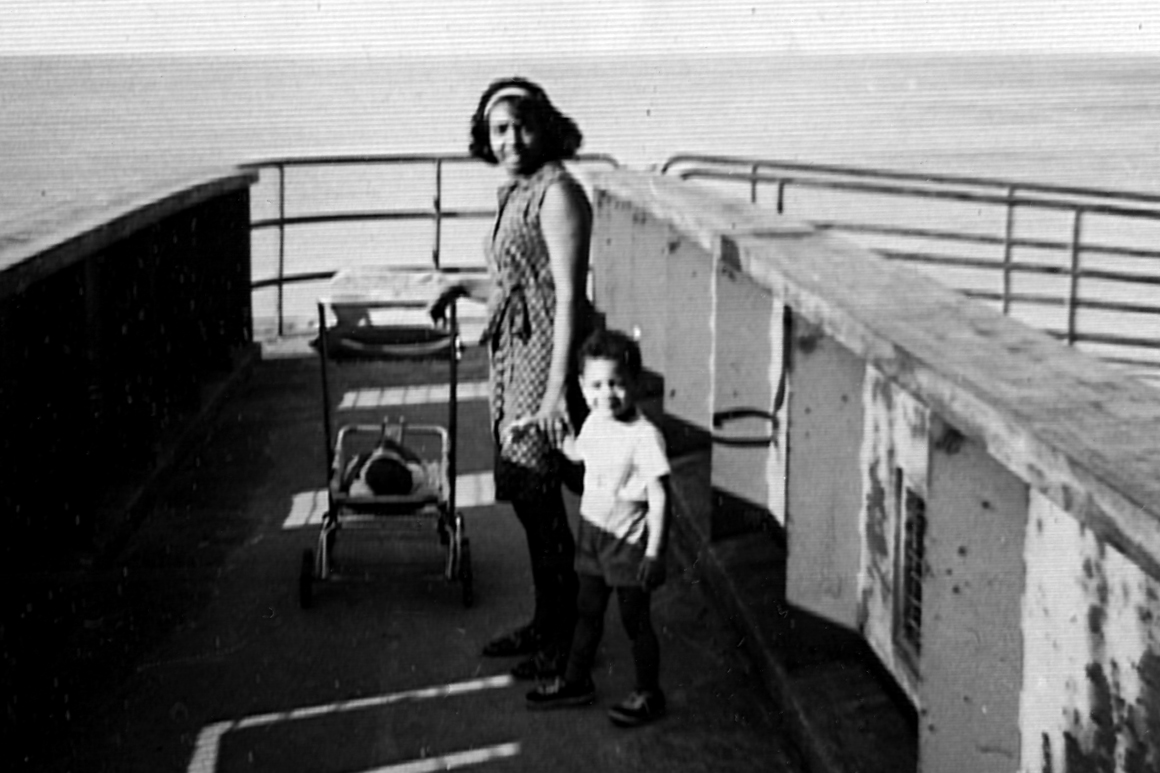

Weldon Rougeau coordinated the train transportation from Miami to Washington, D.C., for the 1963 March on Washington, site of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s historic "I Have a Dream" speech. His son, Vincent, was just 2 months old.

"Vince and I were at the station to see him off, sitting on a bench, and as babies do, Vince raised his little hand in the air. I'm told it was pictured in the Miami Herald with a headline that said, 'And I Want Freedom, Too,'" says Small-Rougeau, a dietician who worked in schools, public housing and with people experiencing homelessness. "From that day forward, he has always, always been a part of the social justice movement. He'd never been exposed to anything else and that's where he got his dedication to social justice."

Weldon Rougeau became involved with the NAACP in his hometown the year before he left for college at Southern University in Baton Rouge, where he joined CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality.

"Being from the rural South and having been born into a society segregated by race, I felt that I needed to do something," Weldon Rougeau says. "I'm old enough to remember when I was a child, there were places where the water fountains were White and Colored, the restrooms were White and Colored, and if you got on any type of public transport, whether it was a city bus or a Greyhound, you had to sit in the back of the bus."

"I really had to think about what mattered to me and succeeding generations," he continues, "and if I could do anything to help dismantle racial segregation, especially the most obvious forms in public accommodations, public transportation and voting — that would be a very good act to perform and, hopefully, it would result in something very positive happening to American society and particularly the community that I came from."

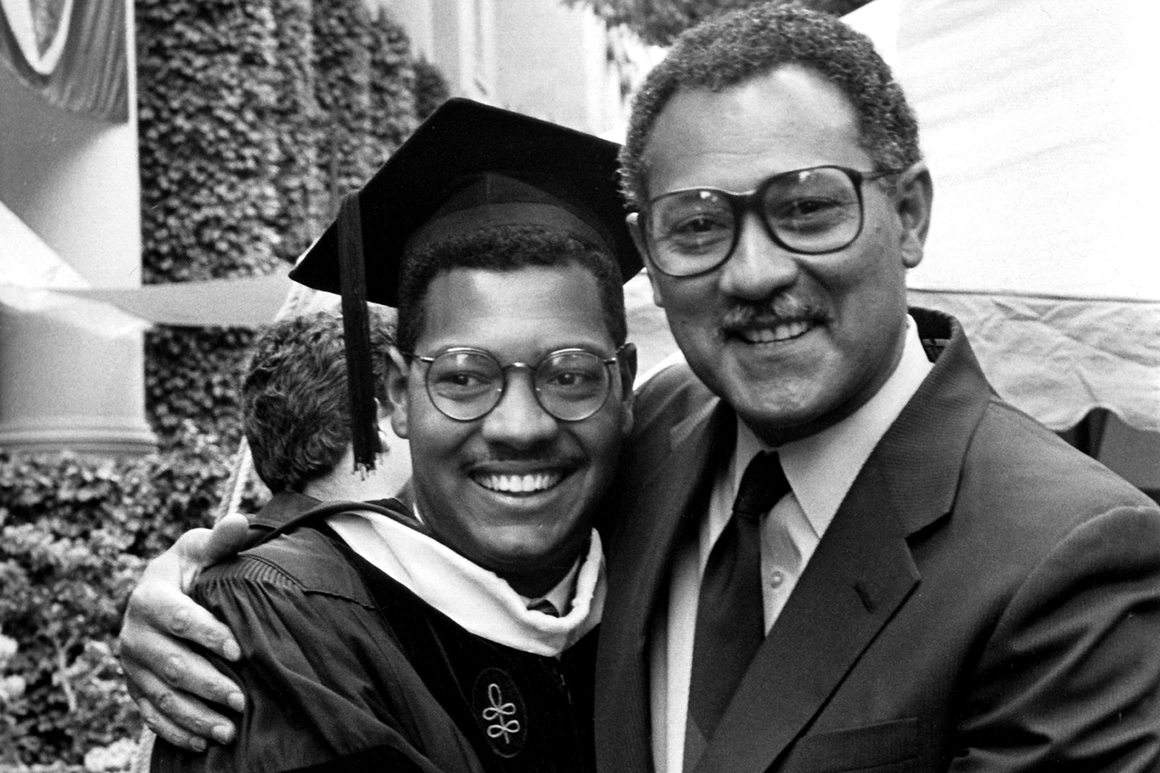

In 1961, he was arrested and jailed for three weeks for protesting a segregated lunch counter and the lack of Black employees at a Baton Rouge department store. His second protest earned him 58 days in solitary confinement — and a quick expulsion from Southern University. As a state school, Southern had to listen to the state board of education, which wanted "troublemakers" like Weldon Rougeau off campus. Vincent was young when Weldon headed to Loyola University Chicago to complete his undergraduate education, after which he enrolled in and graduated from Harvard Law School.

"Throughout the early part of my childhood, my father was also trying to finish his education — the consequences of being expelled," Rougeau says. "That was very life-changing for all of us and also laid a foundation that put education very much at the forefront of our family's life and my parents' commitments. They were very committed to ensuring that we, their children, had access to the best possible educational opportunities and also providing opportunities for others."

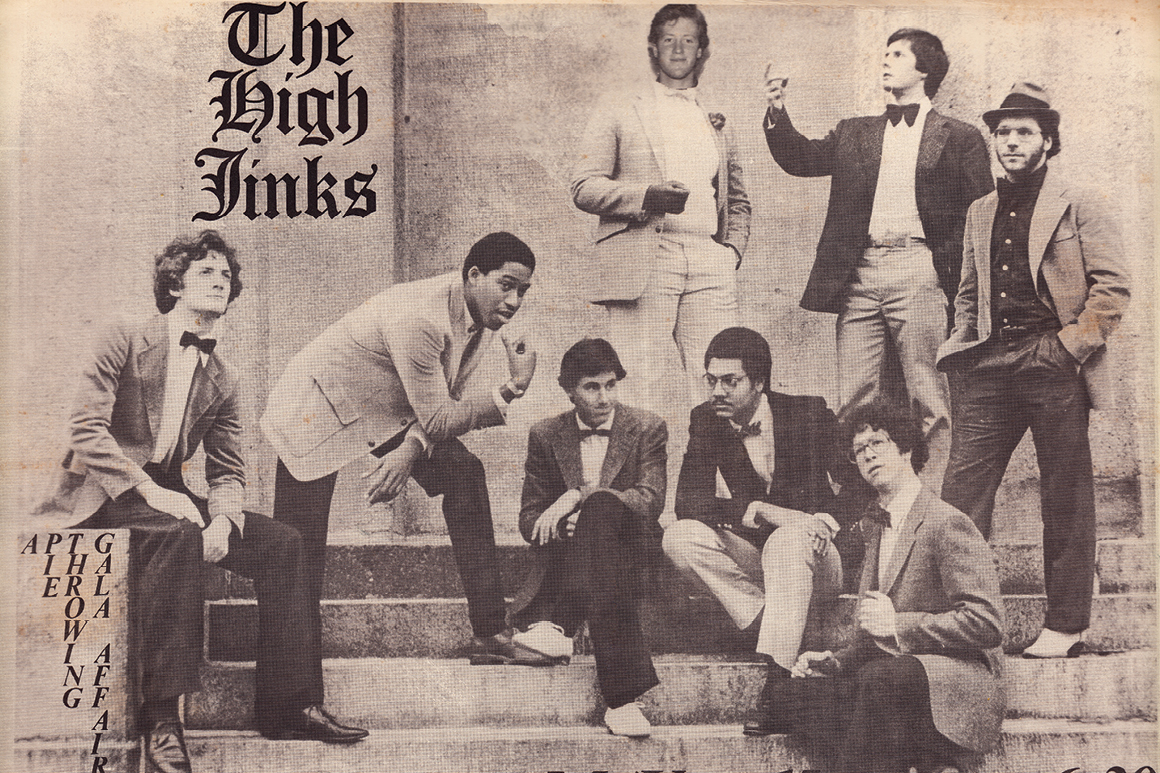

When it was time for Vincent Rougeau to pursue college, he studied international relations at Brown University, graduating magna cum laude, and followed in his father's footsteps, attending and graduating from Harvard Law.

"What my parents were trying to do in the Civil Rights Movement was to allow this country to gain the full advantage of all of its people in a meaningful and dignified way," Rougeau says. "And so, in ways large and small during our childhood, they tried to make sure that we always saw the dignity in others."