In literature, one indicator of a character's enduring effect is to be known by a single name. Think Hamlet, Ripley, Scout, Dracula, Heathcliff.

Scrooge.

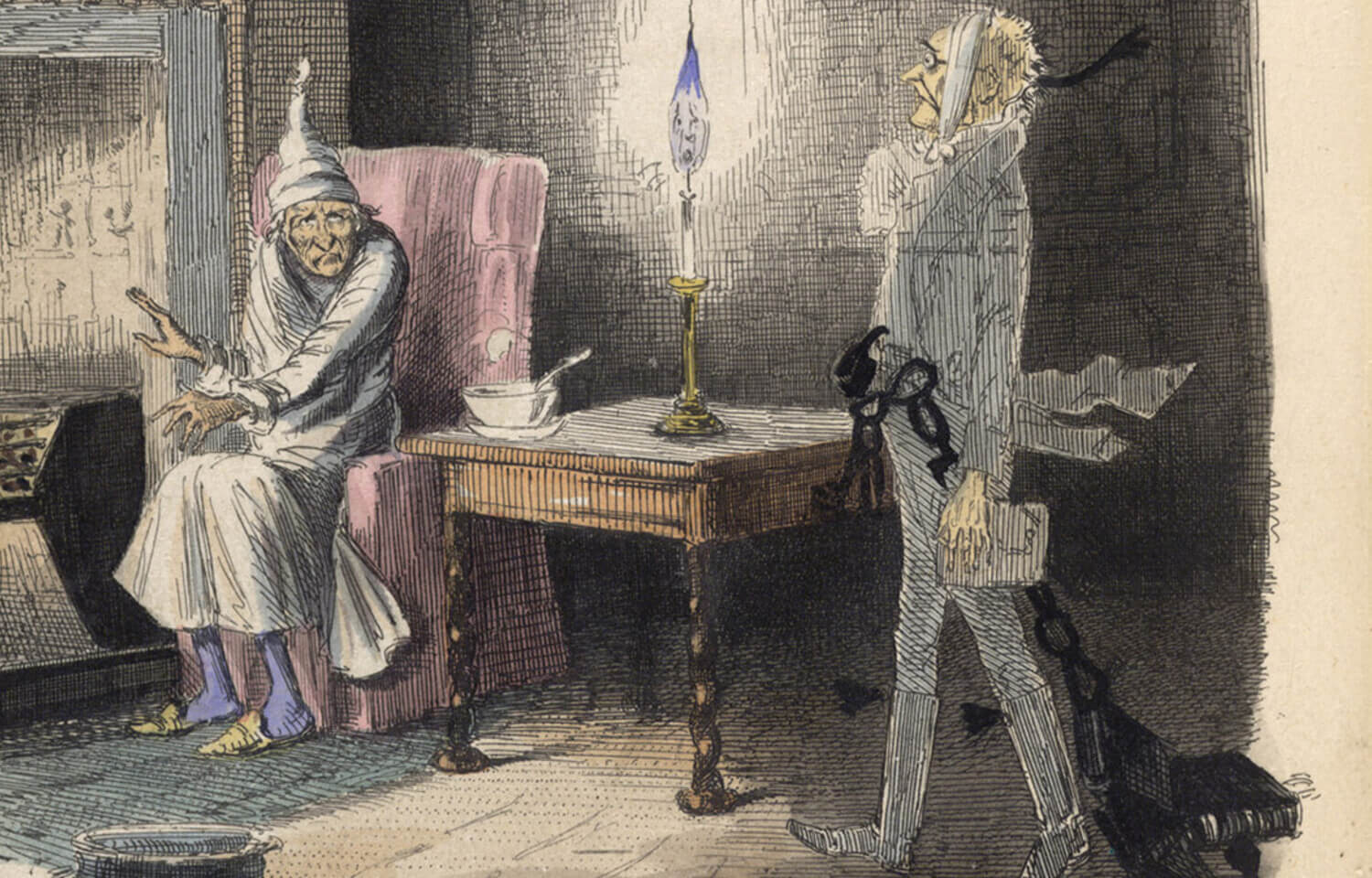

A late-blooming leading man, Ebenezer Scrooge is not star material by any standard. No main character energy to speak of. He is not high-born like Hamlet and not nearly as charming as Scout. Arguably, even Dracula has more charisma than the miserly, misanthropic, judgmental and uncharitable loner that is Ebenezer Scrooge, central character of "A Christmas Carol."

And let's not forget, too, that despite its sentimentality, Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol" is a ghost story — more Stephen King than Nicholas Sparks in plot and tone.

So it is somewhat peculiar that the genre-blending "A Christmas Carol" endures as the most persistently popular of Dickens' works. It might even have been slightly irritating to the most significant author of the Victorian Era, said Debra Gettelman, associate professor of English and dean of the class of 2027, who teaches courses on Dickens and Dickensian fiction.

"Dickens was not surprised that 'A Christmas Carol' was commercially successful when it was published; he was writing a known genre and by 1843 all but one of his novels had been wildly successful," Gettelman said.

And when he started public readings of his work, Dickens knew "A Christmas Carol" was a crowd-pleaser, she added.

But "A Christmas Carol" and Dickens' other Christmas books were of "a more ephemeral, occasion-based genre than his 14 novels, each of which took over a year to publish in serialized installments," Gettelman said. "He wrote four such Christmas stories in five years. So, he would be, perhaps, slightly irritated that it is still his best-known work, in part because he thought the later Christmas books were better."

Gettelman smiled.

"So, yeah, I think Dickens would be amused and maybe annoyed that this story is how he's known by so many now."

'To move readers' hearts'

Dickens knew that Victorians had an appetite for the spectral. Christmas ghost stories were part of a European folk tradition, Gettelman noted: "The darkness of winter, with family gathered around the fire, made the perfect setting for such tales. In the Victorian period, the ghost story set (and published) at Christmas time became a commercially successful genre."

Technology and education created an audience eager for such tales, Gettelman said.

"With the technological expansion of printing, which made printed material cheaper and accessible to more people, and the social expansion of literacy, publishers were as eager for new content as the many streaming services are today," she said. "And this was a popular genre that sold well.

"This wasn't a novel planned out in parts that would be published over the course of a year," she added. "He wrote 'A Christmas Carol' in six weeks."

Dickens knew his market. He also understood how fiction could be deployed to drive social change.

According to a 2014 documentary "The Origins of 'A Christmas Carol'" produced by the British Library, Dickens was moved to write his ghost story after reading an 1843 report from the Parliamentary Commission on the Employment of Women and Children. The report disclosed the horrid conditions under which young children worked. Dickens, a vocal critic of the vagaries of the Industrial Revolution, saw writing — and, particularly, fiction — as a means not only to inform people of injustices done to the most vulnerable members of Victorian society, but also to make the reading public care, Gettelman said.

"Dickens' whole orientation was towards using fiction to move readers' hearts and minds to care about the poor," she said. "His was a moment when there was no social safety net."

Midway through the 19th century, England had industrialized ahead of the rest of the world. "And so there's this rampant, unrestricted capitalism creating this enormous gap between rich and poor with no social safety net at all. No child labor laws, nothing," Gettelman said.

Dickens once aspired to be an actor but missed an audition due to illness. The theater's loss was literature's gain, she said. And Dickens did enjoy an acting-adjacent career in theater doing those aforementioned dramatic readings of not only "A Christmas Carol" but also "Oliver Twist" and other works, which expanded his reach and furthered his message.

Timeless and timely themes such as the ones Dickens' work presents — income inequality, social justice, greed, exploitation, marginalization, regret and redemption — make his novels relatable to today's students, Gettelman said. In her fall 2024 Dickens fiction course, Gettelman taught "David Copperfield" alongside Barbara Kingsolver's "Demon Copperhead."

Kingsolver's 2023 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel follows the plotline of "Copperfield" to examine the opioid crisis in modern-day Appalachia. "These people have been exploited and taken advantage of by the coal industry and by the pharmaceutical companies that went in and marketed opioids there. And not only does no one care, but everyone puts them down and has all these negative stereotypes about them," Gettelman said. "And so Kingsolver has someone who's a kind of child, who's been mistreated and had a hard time like David Copperfield, tell his story of growing up there.

"Dickens really could be of our moment," Gettelman said.

If alive today, though, Dickens might've rethought "good as gold" Tiny Tim, Scrooge's cute kid co-star. His famous line, "God bless us, every one!" falls flat with a modern audience, Gettelman said.

"The one thing that hasn't worn well about Dickens is the sentimentality," she said. "Students are definitely comfortable with sarcasm and irony and those kinds of voices, but less so with that sort of earnest sentimentality."