A police escort guided the Holy Cross women’s basketball team from their hotel to the entrance of Carver-Hawkeye Arena. Fresh off the program’s second-ever NCAA Tournament victory two days prior, the Crusaders stepped off the bus and into an alternate universe — or, perhaps, a glimpse into the future.

More than an hour before tipoff, Iowa Hawkeye fans packed the arena for the first-round tournament game. Nationally, the contest was billed more as the Caitlin Clark Invitational than a postseason matchup, as the NCAA’s all-time leading scorer in Division I basketball history played her final games on her home court.

The madness of March 23, 2024, continued minutes before the game. Fire cannons erupted as the public address announcer introduced the starting lineups, battling for supremacy against the cheers and screams in the arena.

“It was surreal,” remembers Janelle Allen ’24, a senior forward on last year’s team, who scored 18 points in the matchup.

Among the 14,324 in attendance, a small spec of purple seemed anomalous among the sea of Iowa black and gold. The Crusader contingent consisted of families, like Allen’s brother, a defensive lineman for Iowa’s football team; friends and donors, such as Susan Power Curtin ’93; and administrators, like Kit Hughes, Holy Cross’ vice president for intercollegiate athletics.

Candice Green, last season an assistant coach and now head coach, remembers “just the amount of people and how loud it felt. And then there was a Holy Cross pocket. I’m not going to lie, I felt them.”

Courtside, ABC began broadcasting the game to the world, with viewers witnessing Holy Cross unexpectedly styming Clark and her teammates. The chaotic environment simmered to an anxious murmur as Clark finished the first quarter with more turnovers than shots made — an anomaly for the guard who averaged nearly 32 points in 34.8 minutes per game.

As Clark obliterated national and program records over the 2023-2024 NCAA season, she transcended sports to become a household name, as well as one of the nation’s most recognizable pop culture figures. Celebrities from “Ted Lasso” actor Jason Sudeikis to rapper Travis Scott landed courtside in Iowa City to witness firsthand her ability to drain shots from distances never seen before.

Iowa, a No. 1 seed, led by two over No. 16 Holy Cross after the first quarter. Social media buzzed. “Holy Cross” finished the day as the 30th-most talked about word or phrase on X. As for Google, the College, which usually receives an interest rating of between 25 and 30, skyrocketed to 100 — the highest value the search engine designates.

The tsunami of interest overloaded Holy Cross Athletics’ website, goholycross.com. At the game, Hughes spotted a notification on his cell phone from a rival athletic director: “Your website crashed.”

“I literally fist-pumped and yelled,” Hughes says. “In this day and age, a great measure of an incredible level of success, attention and meaning is that so many people are going to your website that the platform crashes. That’s what happened to us.”

Thirty minutes of playing time later, Iowa emerged victorious. But Holy Cross participated in history. Television ratings revealed that 3.2 million people watched the contest — the highest number for a first-round game and second-highest for a non-semifinal matchup. Among dozens of instant classics, the contest was the ninth-most-watched game of the 2024 women’s tournament.

The data speaks to the overwhelming interest across sports, yet it provides little context of the path cleared for the current athletes. For Holy Cross, guard Kaitlyn Flanagan ’26 wouldn’t have slowed down Caitlin Clark without the mentorship of guard Cheryl Aaron ’87.

Forward Lauren Manis ’20 isn’t drafted by the WNBA’s Las Vegas Aces without guard Sherry Levin ’84 setting the high-water mark in scoring in program history. The team doesn’t enter a raucous arena armed with the belief of achieving the impossible without guard Amy O’Brien Davagian ’99 doing just that in 1997, dropping 38 points on powerhouse Connecticut.

“The journey that women’s sports has gone through, it’s almost, like, ‘It’s about time,’” Levin says.

The data is also void of a vision for future growth, like the possibilities unlocked by young girls and boys playing on a blacktop, launching 3-point shots and calling out, “Caitlin Clark for 3!” It also speaks nothing of the past trials and those still standing in the way.

“We still hear the comments, ‘Oh, women’s basketball is boring to watch,’” Power Curtin says. “I would challenge that person, have they ever attended a women’s basketball game to see the talent?”

The talent has always been world-class. The basketball universe and beyond are finally ready to showcase it. The funding is coming. So, what’s next?

“If women’s sports continue to be prioritized, supported, endorsed and given the media coverage, I think the upward trajectory of where it could go is really limitless,” O’Brien Davagian says.

Talent starts early

Kathleen Courtney, M.D., ’97 arrived early as the coach of a youth girls’ basketball team in Foxboro, Massachusetts. She walked by a handful of boys standing under the basket as their workout wrapped up.

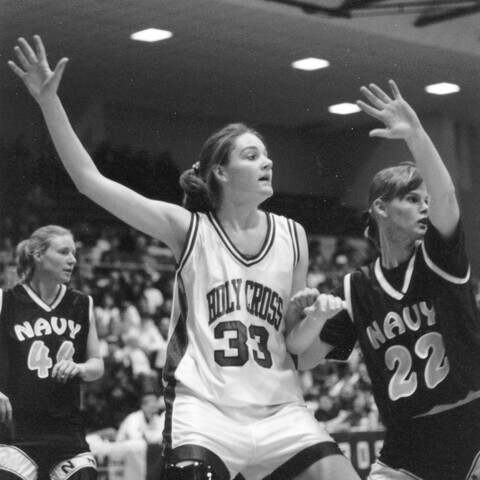

“They were all talking about women’s basketball,” says Dr. Courtney, who had her #33 retired at Holy Cross in 2023. “That made me happy.”

The evolution of the game goes beyond talk.