“As an artist and part of a society of artists, O’Hara was very important —and also under-recognized,” Zafón-Whalen says. “I would argue that his artist friends may not have gotten the recognition they did without him. He died young at age 40, and I believe that if he had lived longer, people would know him better. There is information out there about O'Hara, but it's just not fully synthesized.”

With her new research, Zafón-Whalen hopes to change that.

First-name basis

“There was a moment when ‘Frank O’Hara’ became just ‘Frank’ — Tessa is now on a first-name basis with him,” Sweeney says. “She has read letters from him that possibly no one else has, and has important moments in his life and relationships at her fingertips. She knows more about him than I do at this point. That’s the magic of doing this work with a student.”

Zafón-Whalen may be an expert on O’Hara now, but months before she found herself retracing his steps, O’Hara had been an unknown to her, too.

A double major in English and studio art, Zafón-Whalen connected with Sweeney in spring 2024 when the two met in Sweeney’s office to discuss options for summer research. “Tessa impressed me right away,” says Sweeney, who thought the rising junior would be a great fit to jump in on Sweeney’s MWiP project, a collaboration with the Worcester County Poetry Association that is producing self-guided driving and walking tours tracing the lives of several area poets, along with brochures, scholarly publications and a forthcoming exhibit at the Worcester Historical Museum. (An O'Hara tour can be found here.)

Susan Elizabeth Sweeney, Distinguished Professor of Arts and Humanities, left, was Zafón-Whalen's advisor for the project: "She knows more about him than I do at this point. That’s the magic of doing this work with a student.”

“When Professor Sweeney described Frank O’Hara, I was immediately intrigued because I am also from Worcester, I am connected with my city, and I have always loved English and art — he combined all of my interests,” Zafón-Whalen says.

O’Hara grew up in Grafton, Massachusetts, and attended St. John’s High School in Worcester. He took piano and voice lessons in the city and loved going to the movies at the Loew's Poli Theater, now The Hanover Theatre. In New York City, O’Hara worked his way up from the front desk at the MoMA to become an influential curator. In the 1950s and 1960s, he became the nucleus of a group of surrealist and avant-garde poets, painters, dancers and musicians called the “New York School.”

“I told Tessa, Frank O’Hara was the opposite of Emily Dickinson; he was social, extroverted, gregarious, friendly,” Sweeney says. “If Frank O’Hara was in a room, that room became a salon. He was a great person to have next to you at a dinner party.”

Walking in O’Hara’s footsteps

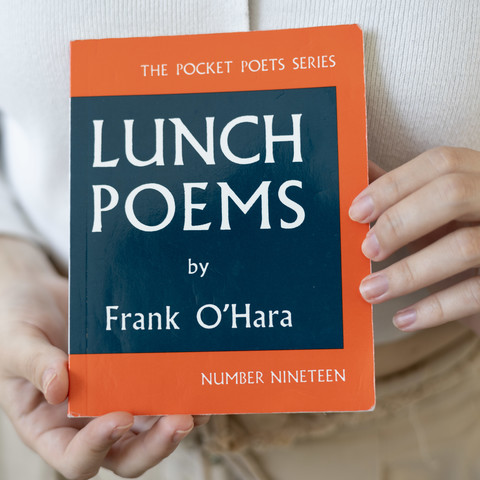

“The first book Professor Sweeney gave me to read was O’Hara’s 'Lunch Poems,’” Zafón-Whalen says. The book is a small collection that O'Hara wrote while walking around New York City on his lunch break from the MoMA, stopping at typewriter stores to type up the poems on sample machines displayed on the sidewalk. He gave many of the poems away, and some are still surfacing.

“The collection was published by City Lights in 1964, and has never gone out of print, which is unusual for a book of poetry,” Sweeney says. “I gave it to Tessa and she read the whole book within a day.”